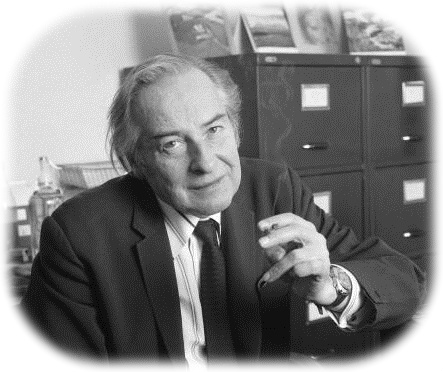

Finished reading again, for the third time, one of my favourite novels, Staying On by Paul Scott. It was published in 1977 (when it won the Booker Prize), a year before Scott’s death at the age of fifty seven from colon cancer.

Finished reading again, for the third time, one of my favourite novels, Staying On by Paul Scott. It was published in 1977 (when it won the Booker Prize), a year before Scott’s death at the age of fifty seven from colon cancer.

Set in 1972 it tells the story of retired British army Colonel Tusker Smalley and his wife Lucy, both eccentric (though she less so), who stayed on in India after independence in 1947, when they were in their forties. Tusker had worked until he was sixty as a merchant for an international shipping agency until forced to retire.

By now, roles are reversed and the formerly ruled and vanquished are in power: “times for them had changed for the better… their own old humiliations were being adequately paid for by new.”

The Smalleys eventually settled in a small Himalayan town and live in the rundown annexe (known grandly as The Lodge) of Smith’s Hotel which they lease from the dictatorial parvenu Mrs Bhoolabhoy, an unprepossessing Hindu woman who bullies her Indian Christian (and third) husband Frankie, in between her migraines and meals. She decides to merge her holding with the glitzy and over-towering Shiraz hotel opposite her place. This means that the Smalleys – who are now down on their finances and struggling (though Lucy does not know exactly how badly) – are to be evicted.

On page one Tusker dies upon receiving notice to quit but the story is told in a series of flashbacks, in imagined conversations and in letters (one written by Tusker is the only ‘love’ letter ‘Luce’, as he calls her when he is being affectionate, has received in her life). Tusker is obnoxious, loud-mouthed, racist and cruel, especially to Ibrahim, their servant, whose inner thoughts, observations and English solecisms are truly hilarious and perhaps mischievous.

The novel is both comical and tragic – powerfully so, and at the end I am in tears at Lucy’s soliloquy. In an earlier scene when arguing with Tusker about their electric stove which doesn’t work properly she says: “I have not stayed on in India to become, in my old age, either a cook or a masalchi [kitchen servant]. You have always pointed out the advantages people like us enjoy over those who have gone home and have to make do without servants even when they can afford them. If we had gone home I should have welcomed turning my hand to what whatever was necessary. But we did not go home and so I don’t welcome turning it.”

Before the British had left, Lucy and Tusker had been subject to snobbery by his military superiors and their wives. But when they left, “Lucy realized that nothing had changed for her, because there was this new race of sahibs and memsahibs of international status and connection who had taken the place of generals and Mrs Generals, and she and Tusker had become for them almost as far down in the social scale as the Eurasians were in the days of the raj.”

What a wonderful novel. After closing the last page we are simply left thinking of Lucy, lonely Lucy, stranded in a ‘strange’ continent, while Tusker finally gets to ‘go home’.