The following feature is reprinted with the permission of Culture Matters and associate editor, Jenny Farrell, who reviews A History of Irish Working-Class Writing edited by Michael Pierse and published by Cambridge University Press, 2018.

The following feature is reprinted with the permission of Culture Matters and associate editor, Jenny Farrell, who reviews A History of Irish Working-Class Writing edited by Michael Pierse and published by Cambridge University Press, 2018.

THIS book is to be greatly welcomed. It is the first study of such scope, attempting to present and analyse the entire body of Irish working-class literature. It begins with the first writings of rural workers in the 18th century and brings the reader right up to the present day.

The study of working-class literature was a significant field of Marxist research in the socialist countries, beginning in the Soviet Union, where the works of such authors were translated, analysed and published from early on. It is left to the German expert Gustav Klaus, author of the afterword, to state this.

Twenty-two chapters examine various aspects of this seriously under-researched field of literature, ranging across three centuries and three continents. The book attempts to give as comprehensive an overview as possible. Its publication coincides with similar companions to the working-class literature of Britain and the United States.

There is of course always a degree of reservation when working-class literature comes under the scrutiny of largely middle-class academics. In parallel to the militancy with which the gender of authors acceptable to writing about women is scrutinised, one might ask: How familiar are these academics with the working-class experience? How much of this experience will be grasped? What do they see, and what not? How high-handed will they be in commenting on the literary production of the working class? These are valid concerns.

In antagonistic class society, the working class comprises of those people who possess nothing but their labour force. They are in an exploitative relationship with the bourgeoisie, and participate only marginally in the yields of their labour. As producers of surplus value, they create the basis of national wealth, yet their living conditions are frequently precarious. The rural proletariat must be included among working-class writers. Small farmers are a periphery group of the rural proletariat, who often hardly exist above subsistence level, while contributing to the national wealth. Equally peripheral to the working class are the ever-increasing number of people in precarious employment, and the unemployed.

Working-class authors must be read not merely in terms of their origins but also of how central this experience is to their writing, how aware they are of the inhuman and war-hungry system that exploits them, how their characters envisage their own emancipation and a better, more humane and peace loving world.

One of the most striking omissions in the book is any recognition of working-class writing in the Irish language. There is no dedicated chapter on this nor is there any meaningful inclusion of writers in Irish.

We mention some of these here to indicate the seriousness of this exclusion. Mícheál Óg Ó Longáin (1766–1837), cowherd and labourer, later teacher and scribe, joined with the United Irishmen in their anti-colonial struggle. From a long line of Gaelic scribes, Ó Longáin, born when the role and prominence of Gaelic scribes was all but lost, eked out an existence, working as a wandering labourer, and living in poverty for most of his life. Neither is there any discussion of the 20th century literary giants Pádraic Ó Conaire, Máirtin Ó Caidhin, Dónall Mac Amhlaigh, or Máirtín Ó Direáin.

Pádraic Ó Conaire wrote the finest (only) no holds barred novel Deoraíocht (Exile) dealing with the raw reality of the Irish working class and Gaeltacht diaspora in early 20th century London and a plethora of short stories in which his identification with the working class is made clear.

Pádraic Ó Conaire wrote the finest (only) no holds barred novel Deoraíocht (Exile) dealing with the raw reality of the Irish working class and Gaeltacht diaspora in early 20th century London and a plethora of short stories in which his identification with the working class is made clear.

Máirtín Ó Cadhain, a left republican who spent the Second World War years in the Curragh prison camp, is arguably the finest 20th century Irish-language prose writer. His collections of short stories and novel Cré na Cille (Graveyard Clay) reflect the grinding poverty and hopelessness of his people, the small farmers and fisher folk of the West Galway Gaeltacht, on whose behalf he agitated all of his adult life.

The prose writing of Dónall Mac Amhlaigh, a building labourer in Northampton and the English Midlands, – especially his Dialann Deoraí (An Emigrant’s Diary) – express the life and feelings of mid-20th century fellow Gaeltacht labourers in England. A member of the British Labour Party, his writing breathes his socialist sensibility.

Máirtín Ó Direáin is the best 20th century Irish-language poet. His childhood in a poverty-stricken household in Inis Mór, Aran, instilled in him a lifelong sympathy for all oppressed, by the capitalist order which finds full expression in his poetry. His fine lament for James Connolly mirrors that of Somhairle Maclean, the leading 20th c Scottish Gaelic poet, of marked communist sympathies, remembered also for his poetic celebration of John Maclean and the Red Clyde.

In the early chapters, there is also a surprising sense of insularity. Although the popularity of the radical Scottish poet Robert Burns among the working-class in 18th- and 19th-century Ireland is mentioned several times, there is no exploration as to why that might have been the case. Indeed, the epochal upheaval of the American and French Revolutions, their unprecedented and hope inspiring effect on the working classes of all of Europe with their promise of equality, comradeship and liberty, are not part of the picture. Yet these events, along with the anti-colonial revolution in Haiti, were major factors in the development of the United Irishmen, who had mass support in Ireland and in the later years increasingly attracted working-class members. Without such an historical context, the writings of the working-class lose the meaning they had at the time.

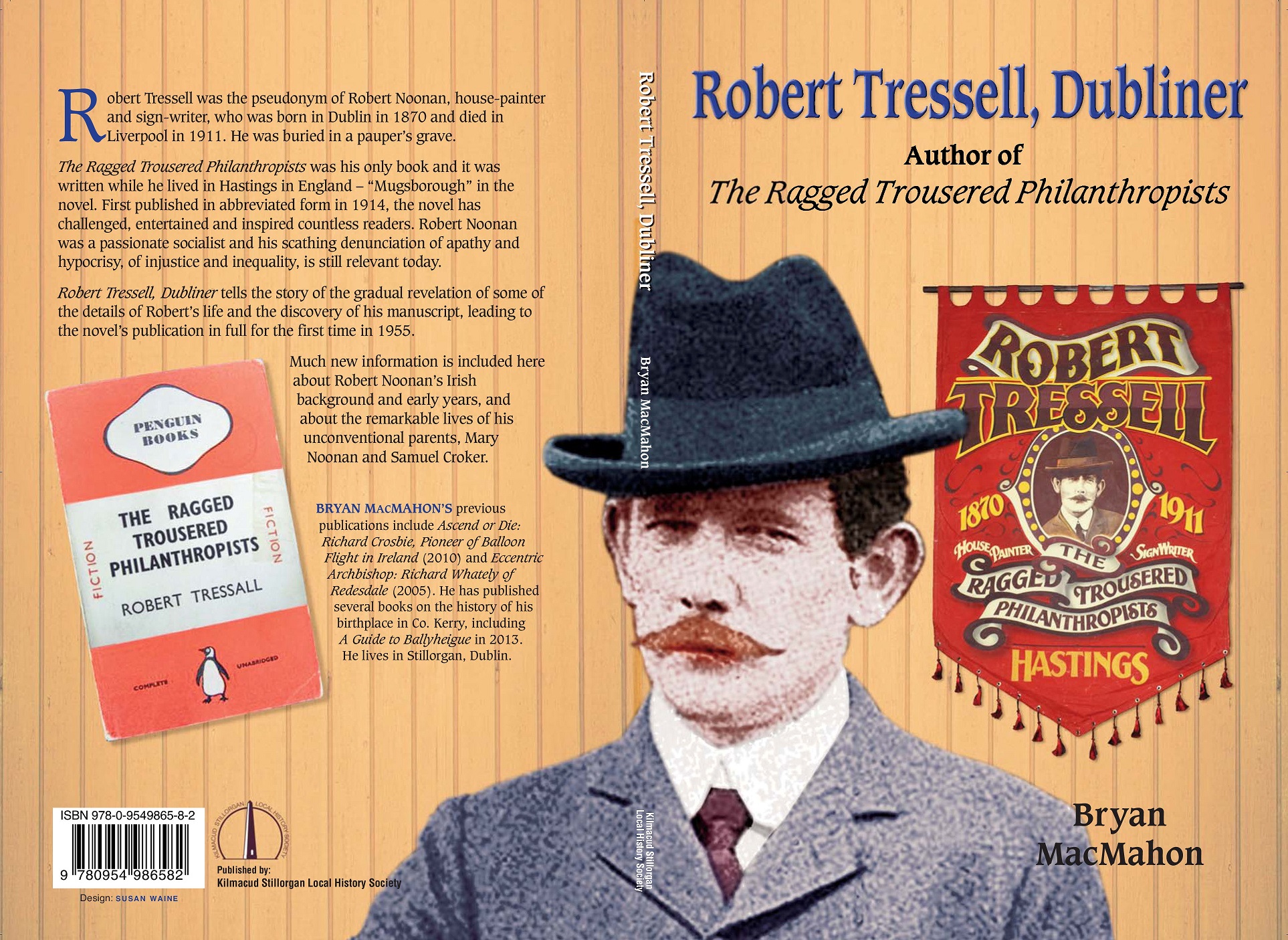

Occasionally, the tone of an author towards the writer discussed may come across as a little patronising. Dublin-born Robert Tressell’s The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists is the first major working-class novel in English literature. It was written between 1906 and 1910 and first published posthumously in abridged editions in 1914 and 1916. Tressell (Robert Noonan) found no publisher and no editor, and the abridged versions removed his socialist ideas from the novel. Its full text only appeared, exactly as he first wrote it, in 1955. The working class has widely embraced the novel as an important text about their experience and written from their own point-of-view. It is not merely about the working-class experience; it also reflects on ways out of it. The Tressell-like main character Owen is a Marxist and tries to explain to his fellow house-painters how the system works, the Great Money Trick, and how to change this life-denying system. Never before in the English realist novel, had the actual labour process been central to the depiction of class struggle. For the first time, Tressell reverses the assumption that life begins where work ends – work is essential to fully lived human life. A character’s attitude to labour is a touchstone of his/ her humanity.

This novel is discussed at different points in the study, but not always in full recognition of its achievement. For example in Michael Pierse’s own chapter, this author generalises to a degree that devalues the differentiated image of the working class presented by Tressell. Paul Delaney on the other hand goes into deeper analysis in his chapter on early 20th century working-class fiction.

In chapters on working-class writers from the North of Ireland, there are glaring exclusions of just such authors. For example, the chapter entitled ‘Poetry and the Working Class in Northern Ireland’ focuses almost exclusively on the not so working-class in subject matter – poets Heaney, Mahon and Longley.

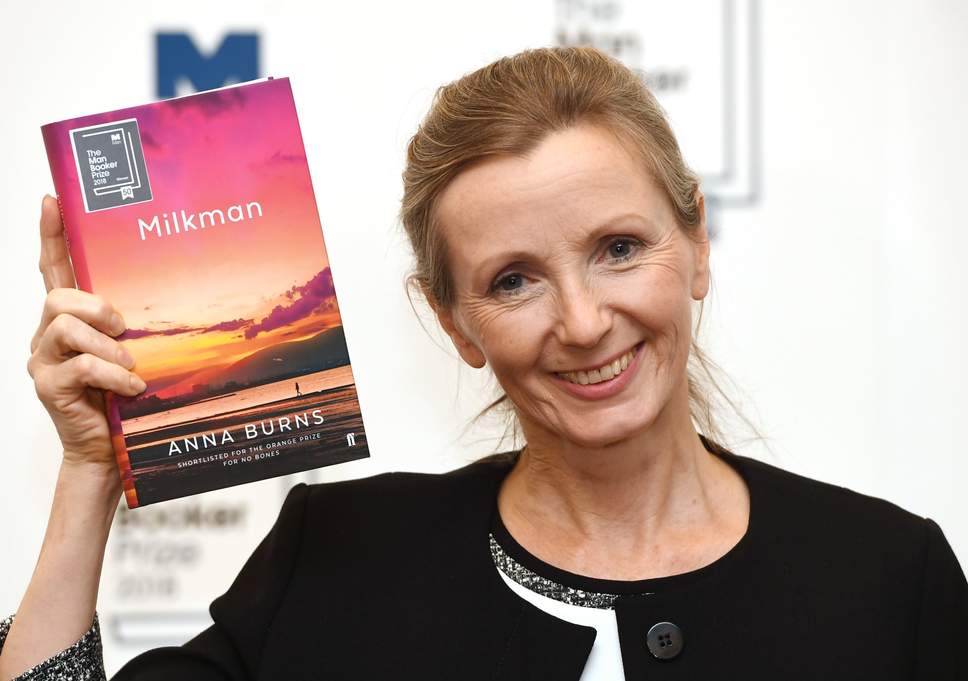

Such emphasis on the existing canon occurs in several chapters and in a way misses the point. Here, there is no reference to Ciaran Carson, bi-lingual (Irish and English) son of a postal worker and highly regarded writer and translator of poetry in both languages. There are other omissions, including again the Irish language tradition, for example Gearóid Mac Lochlainn. Equally, the names of Northern working-class fiction writers do not appear in this book: Danny Morrison, poet Ciaran Carson’s novelist brother Brendan Carson, Sam McAughtry or Ian Cochrane, nor, strikingly, Man Booker Prize winner Anna Burns’s novels. They are not even listed in the many lists of writers that appear without much comment throughout this book.

However, despite these shortcomings, A History of Irish Working-Class Writing is a very good starting point for anybody seeking to discover something about this vital tradition. It highlights the stature of Sean O’Casey, Brendan Behan and other titans of Irish working-class literature. The authors have collected many names and writings of Irish working-class writers in Ireland, Britain, the US, Australia and New Zealand. For this reason alone, this book is an invaluable resource. Some of the better chapters discuss the literature they present in detail and analysis, making for more interesting reading. Two chapters that stand out for me in this respect are Chapter 11 on ‘Solidarity and Struggle in Irish-American Working-Class Literature’ and Chapter 14 on ‘Early 20th century Working-Class Fiction’, both of which look at their texts in terms of socialism and internationalism as well as offering more in-depth analyses. In other chapters, such engagement with the actual texts would have enriched them. For example, Heather Laird writing about working-class Irish Women writers, comments about Rita Ann Higgins that she is one of the few female writers whose poems “feature female speakers with a strong grasp of the part state institutions play in consolidating the power dynamics that underpin the prevailing socio-economic and gender status quo”. After such a statement, the reader expects to be presented with the text and the evidence. Surely, one of the questions we have about working-class literature is not simply the setting but about in what way the writers’ understanding of their class within capitalist society is forged into an awareness of how to bring about a change to their lives.

This book proves that an independent archive of working-class writings must be set up to collect documents and manuscripts often deemed unworthy of publication by commercial publishers and unrecognised by mainstream academics. A great example for such an undertaking is The Working Class Movement Library, founded in Manchester by Ruth and Edmund Frow. Only in this way will important records of working-class lives, such as their autobiographies, but also their other writings be collected as the aesthetic statement of what the lives of so many were and are like.

A History of Irish Working-Class Writing is an academic publication. Priced £79.99, it is ironically beyond the means of the working class. However, despite its shortcomings, it is a valuable reference book. And it creates an interest. Everybody with an interest in working–class writings as the voice of those who are marginalised and silenced in the writing of history, literary and art criticism, should ensure that their local library owns a copy for their readers.