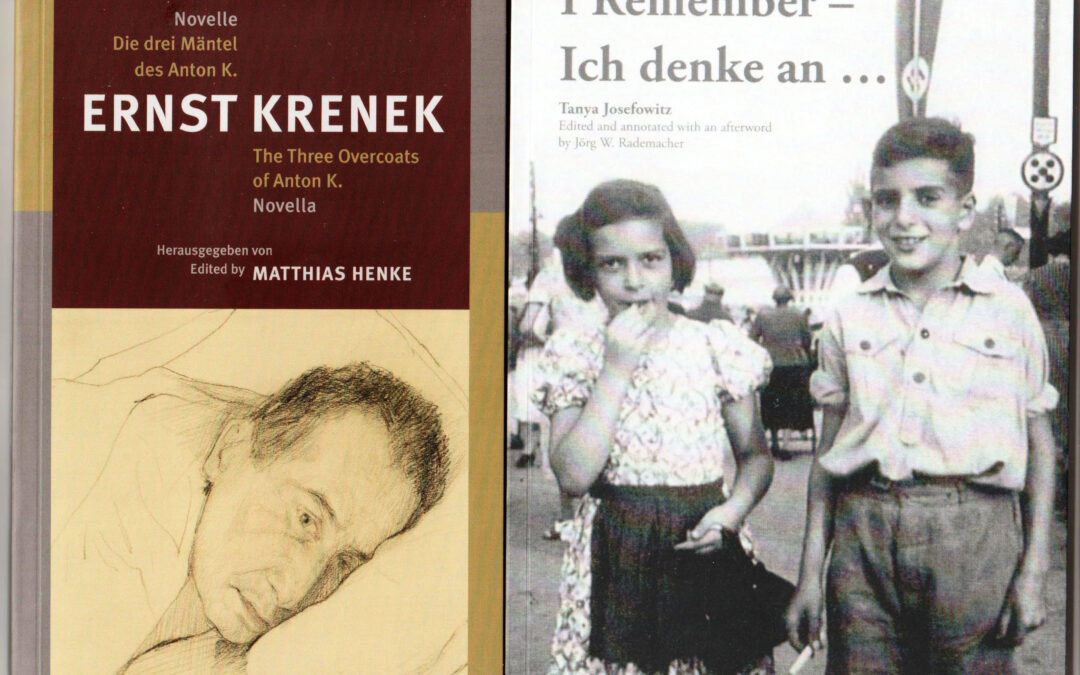

My friend and German translator, Jörg Rademacher, sent me two (bilingual) books on refugees and displacement. The Austrian composer Ernst Krenek’s novella, The Three Overcoats of Anton K., influenced by The Trial, is a Kafkaesque nightmare about a trapped man living outside his unnamed country (Austria) whose passport becomes useless when his country has been absorbed by another country (Germany), and details his attempts to navigate his way through the bureaucracies and consuls of third countries.

In real life Krenek was banned by the Nazis from conducting and eventually moved to the USA with his wife Berta but had to leave his parents behind in Vienna.

Suffering from stress and exhaustion Krenek wrote The Three Overcoats as a form of remedial self-medication, a novella about ‘passport sickness’, whilst he travelled between Warsaw, Helsinki, Gothenburg and London.

It all begins quite simply. Anton is not at home when the postman arrives with a registered letter. He goes to the post office to sign for it only to be told that he can’t. His passport has become obsolete; his country doesn’t exist any longer.

Trundling between various government agencies and getting nowhere Anton rests in a café and takes off his overcoat. After he leaves he discovers that he has the wrong overcoat and that someone must have accidentally taken his. His own coat contains extremely important papers as part of his quest to establish his legitimacy. He becomes obsessed with his case even though he knows he is not a political refugee or an activist. It’s all he talks about. His friends fall away, become bored, and, besides, ‘everybody prefers to live on good terms with the powers that be.’

To find the coat he must cross into another country where his problems mount. An official tells him he’s free to travel to the occupying country. He says he does not wish to travel there because of its cruelty and inhumanity. The official, diplomatically, replies: ‘Yes, I have heard something… But officially it is not known to me. Officially nothing of the sort whatsoever is known to me.’

His nightmare continues when he is required to undergo a medical examination. The doctor asks him bizarre questions, including, ‘What members of your family have been in a lunatic asylum,’ and, ‘How much is three times twenty-seven,’ before asking, ‘Are you Jewish… Jews are in the habit of talking back.’ The doctor then insists he go to another specialist because they now require an X-ray picture of his brain!

Absurdist, sinister and funny his predicament reminded me a little of Yossarian in Catch 22.

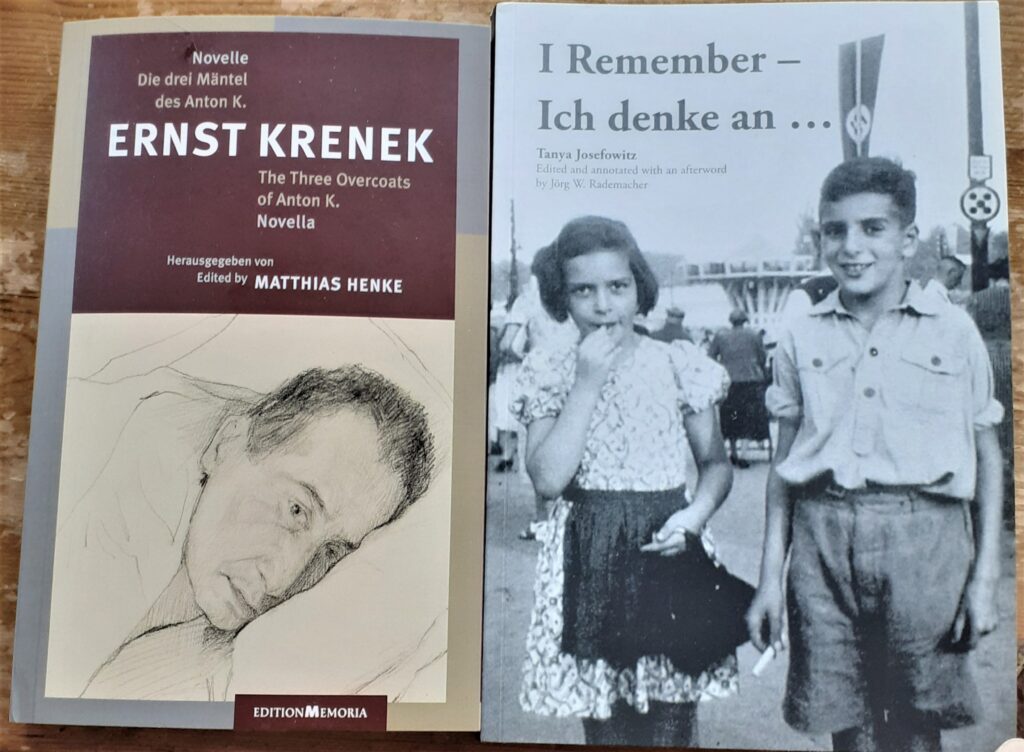

I Remember is a simple, gentle and touching memoir by Tanya Josefowitz, edited by Jörg Rademacher. Very short, it is about Tanya’s, her mother and brother’s escape to America from Hitler’s Germany in 1938.

It opens on the night in 1938 when the Kagan family (Tanya is eight; her brother Vladimir, nine-and-a-half) have friends around. The Gestapo call with a letter ordering the family to leave the country within ten days or face deportation to a concentration camp. Their designation as Russian Jews is what saved them. Their father had been a soldier and POW who despised communism and decided to stay on in Germany after WWI. He married Hildi Wallach.

After receiving the warning their father left Germany and travelled to relatives in the USA to pave the way for Hildi and the two children to follow. The three first move to Munich to the home of Hildi’s mother (who would be murdered in Theresienstadt). They just manage to get a visa to cross into France but their German residence permit expired before they could cross the border.

Were it not for the actions of a kind Gestapo officer (‘a traitor to his cause’, says Tanya) who pays for their overnight stay in a hotel, buys them breakfast and helps Hildi secure the correct transit papers, they would undoubtedly have ended up murdered. This story reminded me of another which I mention in my book All The Dead Voices after I visited the Dutch Resistance Museum. On Christmas Eve, 1941, a member of the Dutch SS came to the door of the Levy family in Varsseveld, a town in the Netherlands. He turned out to be a school friend of their son Johnny and he warned them, ‘Never go to work in Germany. There are camps there where the Jews are being murdered.’ They escaped.

After helping Hildi Kagan, the Gestapo officer confided, ‘I wish I could leave with my family.’

Tanya writes: ‘We did not even know his name, and would probably never see him again… I remember saying a hushed prayer for this man who, I was convinced, saved our lives.’

The family they stayed with in Metz, France, was later deported and killed.

Their father had successfully obtained US visas for them but Tanya’s mother fell seriously ill with pneumonia and had to hide her condition otherwise she would not have been admitted to the US. But they made it through.

Tanya was amazed at seeing black people for the first time, was amazed at the subways, skyscrapers, drug-stores and friendly cops as she discovered a new sense of freedom. Her mother lost thirty family members to the Holocaust.

Dr Jörg Rademacher translated Part I of Ian Kershaw’s work Hitler, the definitive biography of the Nazi leader. He is a teacher of modern languages at a German gymnasium and has written extensively on Oscar Wilde, James Joyce and Victor Hugo. He has also worked closely with Relais de la Mémoire, founded by Shoa survivors in 1989, involving schools from six countries affected by WWII and fascism, which bear witness to the suffering caused by war and, in particular, the Holocaust, and promotes reconciliation.

I myself was a guest speaker at Relais de la Mémoire in Norder, Germany, in October 2015 and gave the opening address.

https://oscar-wilde-blog.de/welcome.html

Honoré de Balzac