Really liked this book – Before The Deluge – a Portrait of Berlin in the 1920s by Otto Friedrich – which was given to me as a present by a couple from Nuremberg, Michael and Marion Wolf, whom I met at a left-wing book fair in Munich last year. The book helps one not only understand the rise of fascism post-WWI, particularly in Germany, but the cultural milieu, the ferment at the bottom of the barrel both life-affirming and squalid.

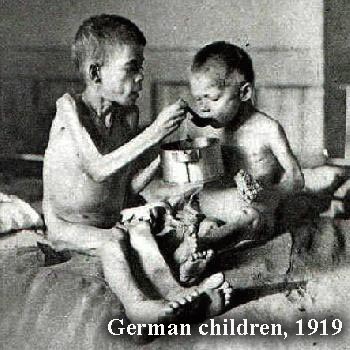

Although there was an armistice the Allies continued to blockade the German coast.

Although there was an armistice the Allies continued to blockade the German coast.

Count Kessler, a diplomat, writer, and patron of modern art, wrote: “Germany lay prostrate. France gave open vent to her desire for our extermination, expressing it monumentally in her Prime Minister’s words: ‘There are twenty million Germans too many.’ The continuation of the blockage after the armistice was rapidly fulfilling this wish; within six months from the armistice it had achieved a casualty list of 700,000 children, old people and women… The German people, starved and dying by the hundred thousand, were reeling deliriously between blank despair, frenzied revelry, and revolution.”

Cakes in the Josty Café in Berlin were made from frozen potatoes and ‘Havana’ cigars from cabbage leaves steeped in nicotine.

One important and pertinent question that Friedrich poses is, ‘What caused the inflation in Germany in the first place?’ One experiences a frisson of déjà vu re Greece today.

“Germans of a nationalist persuasion have always placed most of the blame on the Allied demands for reparations, and it is undoubtedly true that any currency must suffer when the national wealth and the national production are drained to pay international commitments. More hostile observers, on the other hand, accuse the German government itself of trying to perpetuate a gigantic fraud. ‘Goaded by the big industrialists and landlords,’ as William Shirer put it in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, ‘the government deliberately let the mark tumble in order to free the state of its public debts, to escape from paying reparations… Moreover the destruction of the currency enabled German heavy industry to wipe out its indebtedness by refunding it obligations in worthless marks.”

Walter Gropius, the architect and founder of the Bauhaus school, responding to a question about state support of art, said: “Art and state are irreconcilable concepts.”

Art & War

‘Art never stops war, after all, any more than satire does, or armies of women marching with banners of protest. The only thing that stops war is defeat, not necessarily defeat on the battlefield but defeat in the sense of recognition that too much money is being lost, and, almost incidentally, too much blood. But if art does not stop wars, it may yet convince the survivors that military victory or military defeat need not be our basic standards. “The function of literature,” as Ezra Pound said, “… is… that it does incite humanity to continue living.”

On Kafka & Verisimilitude

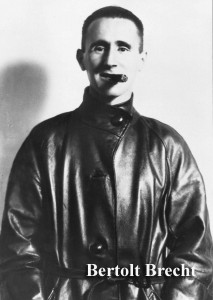

“Like Kafka, Brecht not only made no attempt at accuracy but rejected the whole idea of accuracy. ‘Incorrectness,’ he said, ‘[is] hardly or not at all disturbing, so long as the incorrectness [has] a certain consistency.’”

On Max Reinhardt & the Stage

“A Viennese by origin, and trained as an actor, Reinhardt was short and stocky and rather handsome, with wavy hair and bright blue eyes. He had arrived in Berlin in 1894, at the age of twenty-one, as an actor in Otto Brahm’s repertory company at the Deutsches Theater, and eleven years later, when he succeeded Brahms as head of the company, he set out to revolutionize the fundamental techniques of the stage. ‘The theatre is neither a moral nor a literary institution,’ said Reinhardt. To him, it was a place for display, spectacle, magic. The revolving stage was his speciality, and so were the mysterious lighting effects that nobody else could duplicate. Reinhardt abolished the walls of conventional theatre sets; he abolished footlights and curtains; his actors moved out into the audience and made it part of the spectacle.”

“[Erwin] Piscator’s Proletarian Theatre expressed the guileless belief that the drama was a medium of revolution. The director favoured radical authors like Gorki and Upton Sinclair, and his actors were, at the beginning, not professional performers but unemployed workmen.”

Brecht’s Political Ambiguities – Author in conversation with Stefan Brecht

Brecht’s Political Ambiguities – Author in conversation with Stefan Brecht

“The conversation drifts into the question of Brecht’s political ambiguities – the ambiguity, for example, of a Marxist trying to earn his living in Hollywood (“Every morning to earn my bread,/I go to the market, where lies are bought,” Brecht had written. “Hopefully/I join the ranks of the sellers.”) And of a Marxist cooperating docilely with the House Un-American Activities’ Committee, supposedly investigating Communism in Hollywood. (“Have you ever made application to join the Communist Party?” asked the attorney for the committee, and Brecht said, “No, no, no, no, never.” And Ring Lardner, Jr.’ one of the so-called “Hollywood Ten” who went to prison for refusing to cooperate with the committee recalls that Brecht was very apologetic after the hearing but said he had to testify because he had to get back to Germany. And when asked whether Brecht hadn’t been a little – well, perhaps a little grovelling, Lardner indignantly says, “No, he was not, he was not grovelling.”) And of the famous libertarian finally returning, with an Austrian passport, a Swiss bank account, and a West German publishing contract, to his own state-subsidized theatre in Stalin’s colony of East Germany. (“We know,” wrote Günter Grass, in his accusing drama, The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, “that while the revolt in East Berlin [in 1953]… was going on, Brecht did not interrupt his rehearsals … We know that Bertolt Brecht took an attitude of wait-and-see… In my play the construction workers, who interrupt the Boss’s rehearsals, [believe] that he is somebody whom the government supports and tolerates as a display of cultural property, or as a kind of privileged court jester.”)

“And of that strange Brechtian story, which is fundamental to Brecht’s view of life, and to such great creations as Mother Courage and Galileo, of the man who said no. There once was a little man who lived peacefully in a little house, and one day a powerful official came to his door and said, “Will you serve me?” The little man did not say a word, but he let the official into his house, and for seven years, he bowed down to the official, and fed him, and served him. Finally, the official grew so fat and indolent that he died. The little man quietly wrapped the official’s body in a blanket and threw it out of his house. “Then he washed the bedstead, whitewashed the walls, breathed a sigh of relief and answered: ‘No.’”

“Yes, I think I understand that,” says Stefan Brecht, putting his feet on the desk, with the gray suede boots raised high. “It’s about hypocrisy, the hypocrisy of thinking no but doing yes. So many people do that. You’re wearing a white shirt and a tie – that’s doing yes.”

Two centuries before Brecht, John Gay (who wrote Beggar’s Opera) was a Brechtian. “As a youth, he served a disagreeable apprenticeship to a London silk merchant. Trying to make his living as a poet, he became an unsuccessful supplicant to various aristocratic patrons. He invested his savings in a South Seas stock swindle, and the subsequent bankruptcy brought him to physical collapse. On his grave is inscribed one of his own couplets:

Life is a jest, and all things show it.

I thought so once, and now I know it.

On Lotte Lenya (who married Kurt Weill)

“She was and is one of the phenomena of the musical theatre, now past seventy, but still singing and still fascinating audiences with a talent that defies description. She has, according to one critic, “a face like a clock without a second hand.” According to another, “she has a rasping voice that could sandpaper sandpaper, and half the time she does not even attempt to sing, but she can put into a song an intensity that is almost terrifying.”

“She was and is one of the phenomena of the musical theatre, now past seventy, but still singing and still fascinating audiences with a talent that defies description. She has, according to one critic, “a face like a clock without a second hand.” According to another, “she has a rasping voice that could sandpaper sandpaper, and half the time she does not even attempt to sing, but she can put into a song an intensity that is almost terrifying.”

On Mac the Knife

“Harold Paulsen, who was to play Macheath, insisted on wearing a blue bow tie that everyone else hated. He also insisted that his own role should be strengthened. Why begin, he argued, with Mr Peacham singing his gloomy ‘Morning Chorale’? Why not begin with a song about him, the highwayman, with his blue bow tie. Brecht agreed, at the last minute, and wrote, literally overnight, the Morität that is now known as ‘Mac the Knife.’ And Weill, also in one night, wrote the haunting melody that achieved the final triumph of his music over Brecht’s play…

“That opening night was, of course, a legendary triumph, and of every ten Berliners alive today, at least three claim to have been in the cheering audience. But the success was not without its ironies. One was that the ‘proletarian’ creators, Brecht and Weill, became rich. Another, more significant, was that the sleek and the wealthy, flocked to the Schiffbauerdamm to hear themselves derided and denounced.”

On Herman Mann’s The Blue Angel

Sternberg, the director, “changed the basic idea from the downfall of an autocrat to the downfall of a puritan, a victim not of social forces but of infatuation. And there is no recovery. The teacher’s degradation continues inexorably toward the harrowing scene in which he is forced to totter on stage at Lola’s cabaret and to crow like a chicken while an egg is broken over his head.”

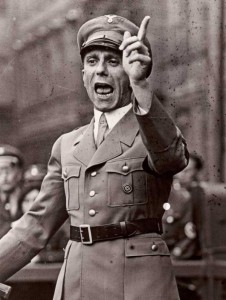

On Goebbels

On Goebbels

“Several years later, looking back on his career, Goebbels told an associate that he had helped the Nazi cause in four essential ways: by introducing Socialism into a middle-class group, by “winning Berlin,” by working out the style of the party’s public ceremonies, and by the “creation of the Führer myth. Hitler had been given the halo of infallibility.”

“There was considerable truth in these boasts, particularly the last one, for, as a series of elections soon demonstrated, millions of Germans began to believe that Adolf Hitler, a semiliterate incompetent, a failure in everything he had ever attempted, somehow had the skill and intelligence to solve the nation’s problems. One of the most willing believers in the “Führer myth” was, understandably enough, the nervous and uncertain Führer himself. When one of his supporters once told him, in the course of an argument, that he was mistaken, Hitler angrily answered, “I cannot be mistaken. What I do and say is historical.””

In The Mass Psychology of Fascism Wilhelm Reich says that it seemed absurd to blame Nazism on any one class or nation. He argued that Hitler’s movement was simply “the organized political expression of the structure of the average man’s character… There is not a single person who does not bear the elements of fascist feeling and thinking… In its pure form fascism is the sum total of all the irrational reactions of the average human character.”