Today’s Irish Examiner carries my review of The Liar by the late Danish writer, Martin A. Hansen, translated by Paul Larkin. I love European literature written just after the ending of the Second World War and this translation is a literary treat.

-oo0oo-

The cruelty, brutality and barbarity of the war initiated by Hitler and Nazism in Europe, the moral, spiritual and physical destruction it caused, created such societal and individual trauma that humankind could have been completely overwhelmed by despair. The communal survival instinct ultimately triumphed, and although with liberation came great relief, below the surface of celebration remained an inescapable insecurity around whether life had any purpose or meaning.

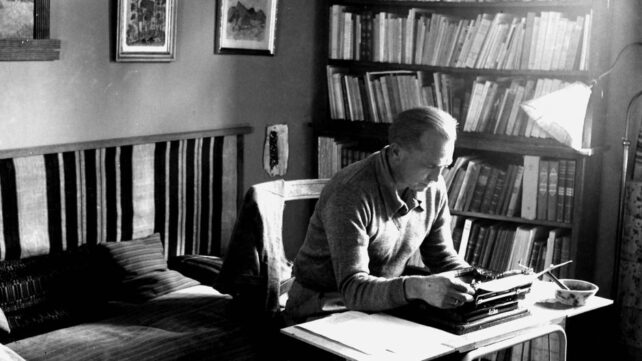

Martin A. Hansen, who was to become one of the most widely read authors of his day before dying young at forty-six, came from a farming family and worked as a teacher. During the five-year Nazi occupation of Denmark, he wrote for the underground press wherein he justified the assassination of informers (something which later troubled him).

However, in his novel, The Liar, which began life as a serial on national radio and garnered a huge audience in 1950, before becoming a literary bestseller (and a literary treat in Paul Larkin’s translation), the late war is relatively mooted, though its oppressiveness pervades like some cosmic microwave background, with ‘post-war mental cases… moaning about how everything is meaningless and pointless.’

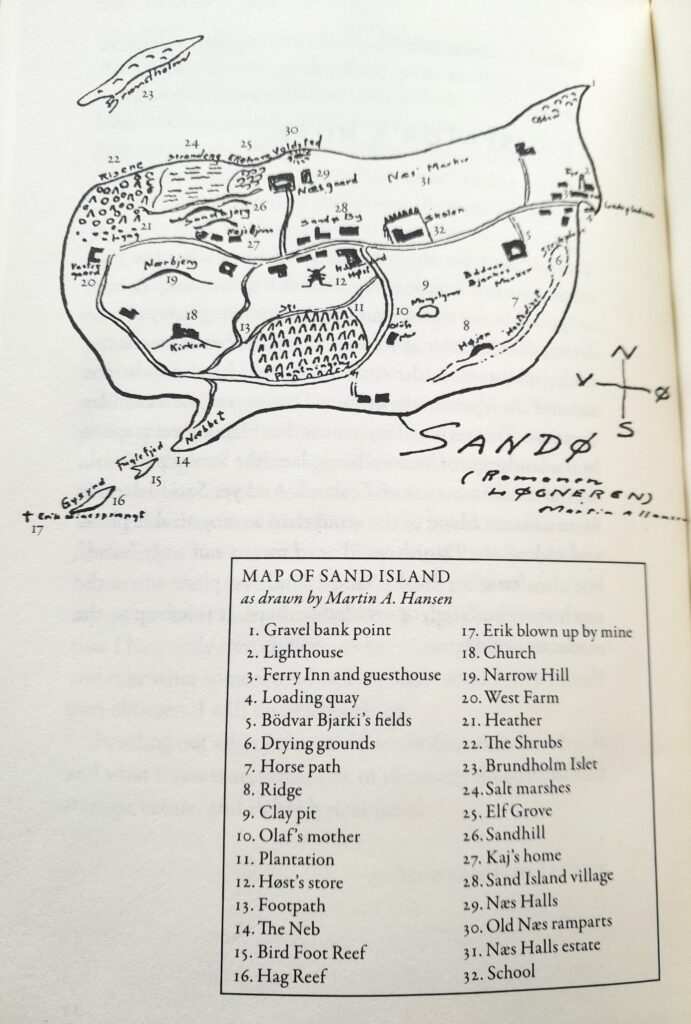

Forty-year-old Johannes Lye is a blow-in on tiny Sand Island, where he is the schoolteacher, sometimes postmaster, and stands in as Sunday preacher when the island is landlocked by winter sea ice. His best friend is his hunting dog Pigro and he draws great succour from the island’s wild isolation, fauna and flora, its wintering birds which mark the passage of time. Indeed, nature and its melancholic beauty, in its redemptive powers and ruthless austerities, are characters themselves, determining fates, moods, sorrow and joy.

He is a human being settling into his soul and recognises that ‘man must reconcile himself to a life of disquiet if he is to live a complete life. That this is the human lot.’

Written as a year-long diary to an imagined reader (Nathan), it is Johannes’ account and re-accounting of life among the small fishing community which teems with incident and intrigue. Despite often being an unreliable narrator, for reasons of self-protection, Johannes is nevertheless a worthy hero, if reserved, self-deprecating despite some vanity, struggling for honesty and truth, hiding his wounds with a jovial, deadpan humour.

He recognises his own flaws and hypocrisy—a preacher carrying on a desultory affair with an older woman, Rigmor, wife of his friend ‘Squire’ Frederik; and is in love with his former pupil Annemari whose partner Olaf and father of her child is stuck on the mainland during this ice age. An opportunity for flirtation. Troubled Olaf is an island hero for swimming three miles through stormy waters after his dingy capsized: but knows that he is a fraud—it was his misadventure that led to the drowning of his friend Niels.

Johannes is jealous of and attempts to undermine Annemari’s affair with a visiting engineer Harry (‘a glorified hole digger’, he calls him), and a former member of the Dutch resistance who has reconciled himself to the deaths of those he killed.

Johannes gives contradictory accounts of how he ended up on Sand Island. Like Hesse’s Knulp, he was a young promising scholar until his teenage girlfriend Birte broke his heart, untethering him from his moorings. In another less credible version he tells Annemari that he later met Birte and cruelly and deliberately broke up her marriage. He feels the need to paint himself in bad light yet he can be a confidante and is kind at heart. He arranges the transport to a mainland sanatorium of a tubercular child, Kaj, from a poor family, of whom he is very fond; contrives work for the kid’s father, cutting down trees; and innocently offers shelter in his home to Rascals Room’s young pregnant barmaid, the single Elna, regardless of scandal.

He can also be very funny: ‘No doubt there’ll be people saying the schoolmaster … has gone too far again. What the hell’s he playing at, taking pudgy, slutty Elna the barmaid into his private home?’

He also likes ‘a dram’ and in one hilarious incident drinks before giving a comical and sinister ‘anti-sermon’, preaching the opposite of the gospel, deriding God’s cruelties, while his unperturbed congregation suspects he’s been on the sauce again.

He calls himself ‘a charlatan’—but aren’t we all, the stratagems we deploy daily to get through?

Poor Johannes, forever struggling with existential angst, but ‘now at home with these people’, his fate ‘eternally bound to this lump of rock and soil in the middle of the sea.’

It is 1950. Switch on the radio. Listen, be settled and be charmed and possessed.