Cahir O’Doherty, Arts Editor, Features and Travel Writer for The Irish Voice, Irish America magazine and IrishCentral.com reviews Patrick Anderson’s book, Rewriting The Troubles: War and Propaganda, Ireland and Algeria. This review first appeared in The Irish Voice on 5 June, 2023.

IT’S EXTRAORDINARY how consistent the experience of colonialism can be across cultures. From Ireland to Algeria, colonized people can point to key moments and military ploys that have broadly echoed each other in ways we are still only appreciating.

The official British narrative about the Troubles is that there was a religious conflict going on in Ireland.

In this telling, the rise of an Irish Republican insurgency can be dismissed as a sectarian movement with its roots in chauvinism.

But if the source of the conflict was instead the long legacy of British colonialism, as historian Patrick Anderson argues in Rewriting The Troubles, War And Propaganda, Ireland And Algeria then the focus should really be on London.

“I want to look at what the British have brought about,” he tells IrishCentral.

“Because it’s not spontaneous, it’s not the work of Irish religious zealots who are in it for some atavistic reason.”

“People don’t just decide to take on one of the best trained and equipped armies in the world for something like that. You don’t get kids from West Belfast and North Belfast to do that so easily. Something major has to make them do it.”

Anderson continues: “When all is said and done, we have to ask ourselves what was this conflict all about? And the British are increasingly finding it difficult to keep up their lie, which is that they were impartial actors in the middle,” he says.

“I mean victims’ families have had to drag them to supranational courts in order to prove collusion, and then you have to get Americans to come over and help too, you have to get US Senate Committees looking at them. So it’s been increasingly hard for them to maintain their story. What should come out of it in particular, the big one, is the collusion denial. It completely shatters the whole British narrative. Once that is shattered, then they are seen as a participant in the conflict, not the referee.”

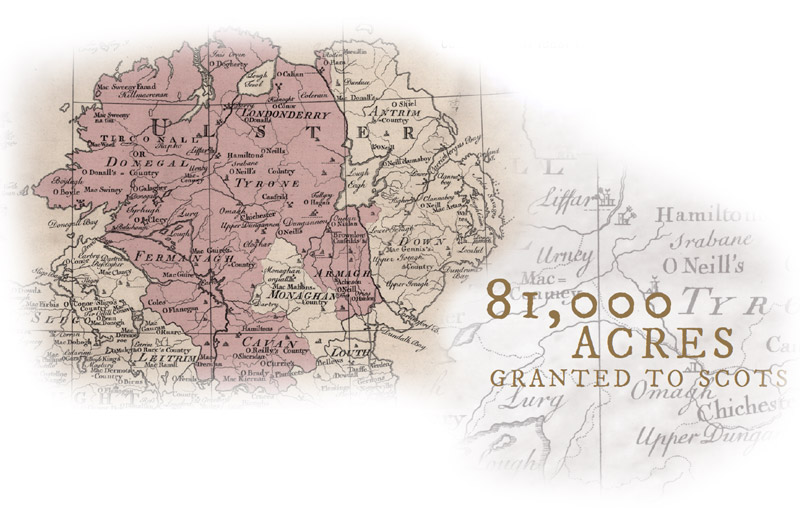

In this magisterial study, Anderson examines the parallels between the Plantation of Ulster and the French settlement of Algeria. Politicians in Paris have described Algeria as France’s Ireland, Anderson reminds us. The Algerians themselves studied and took inspiration from Michael Collins and the IRA’s campaign to drive out the British in the 1920s.

But the parallels run deeper and Anderson skilfully compares the two remarkably similar conflicts, paying particular emphasis to the responses of London and Paris to their violent colonial legacies in both countries and to the way that British propaganda continually cited a military restraint they didn’t actually practice, in stark contrast to what they called French ruthlessness.

Managing reports about English colonial exploits in Ireland is a centuries-old practice and Anderson is almost impressed by the efficiency with which it has been practiced, from the time of Giraldus Cambrensis through Edmund Spender to the news reports during the Troubles, when the British press (and quite a few journalists in Dublin) often ignored evidence of collusion and torture and acted instead like the British Army’s stenographers.

Meanwhile, Unionism, having once embraced and celebrated its planter background, has in more recent years sought to distance itself from its own colonial origins as colonialism itself becomes a marker of invasion and exploitation.

“There is a strange reluctance to talk about the colonial origin of the Troubles now. Unionism for the longest time revelled in the idea of good planter stock and Ian Paisley always talked about his own good settler stock from Ballymena. But since the Second World War, people don’t want to be seen as colonizers and around the world.”

Settler colonialism is a much bigger question now Anderson avers. “It’s seen in Ireland, Algeria, New Zealand, Australia, all over. It’s when the people who were originally settlers and loyalists but do not want to answer to the mother country anymore. But they’re still dependent on the mother country’s military.”

“So they have to behave themselves, he continues. “With Ulster unionism or the French in Algeria, they want to break away and do their own thing, but they’re still dependent on the mother country. So as England is changing and becoming more democratic their – let’s call them great-grandchildren or offspring that they once sent over – are becoming increasingly hard to deal with.”

To paraphrase Faulkner, the past isn’t dead. It isn’t even the past. As this ground-breaking study reminds us, what unites us as former colonies has inspired resistance and a more sincere way to describe and understand – and climb out of – the disaster of colonialism and conflict that followed in the north.

Rewriting The Troubles can be ordered here – An Fhuiseog