Martin Neary’s book, Madogue Memories, about his life in east Mayo, the perennial toil of maintaining the land, his having to seek work in England to support his small holding, is told with great humility and charm but with a certain melancholia. In his evocative storytelling some parts of it reminded me of that bestselling memoir from the late 1980s, Alice Taylor’s To School Through The Fields.

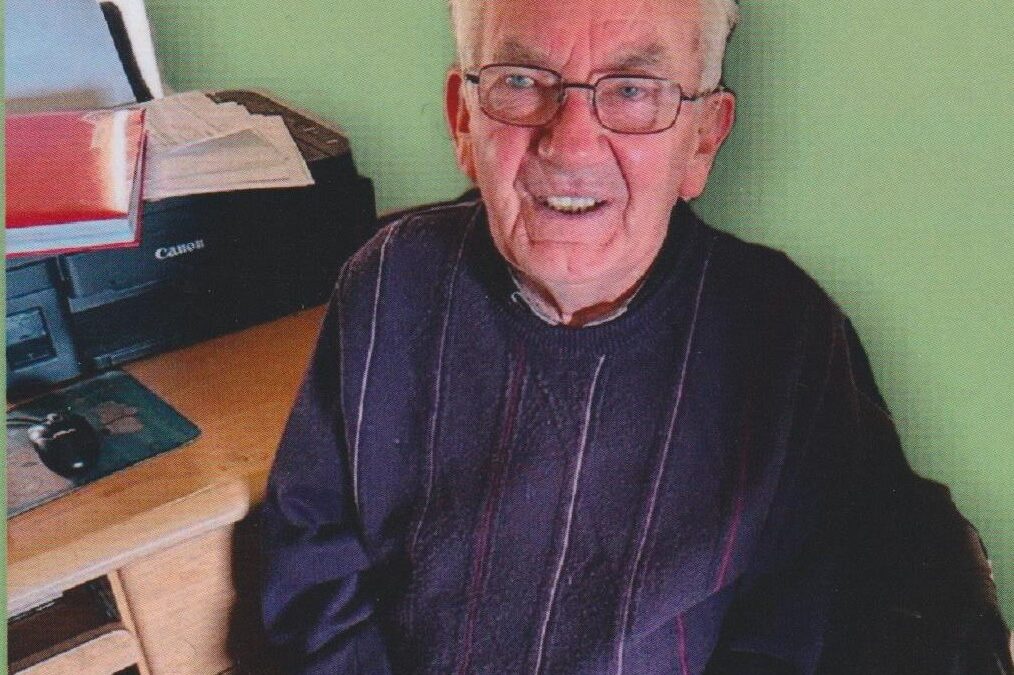

I met Martin recently in Ballina where the fiftieth anniversary of the death of hunger striker Michael Gaughan was marked by a number of events. Physically, the weight of time has bent this eighty-one-year old’s back a bit, but his story is an uplifting little eulogy to all those people whose lives he touched and theirs his. And what a memory he has, even though it clearly pains him the few times he can’t put a name on someone from six decades ago.

There is a fine Foreword to the book by his friend Gerry Murray who praises Martin, a republican and socialist, for bequeathing his homestead to the people of his parish, his beloved community, when he dies. He is also one of the few people who has been granted the right to be buried on his own land.

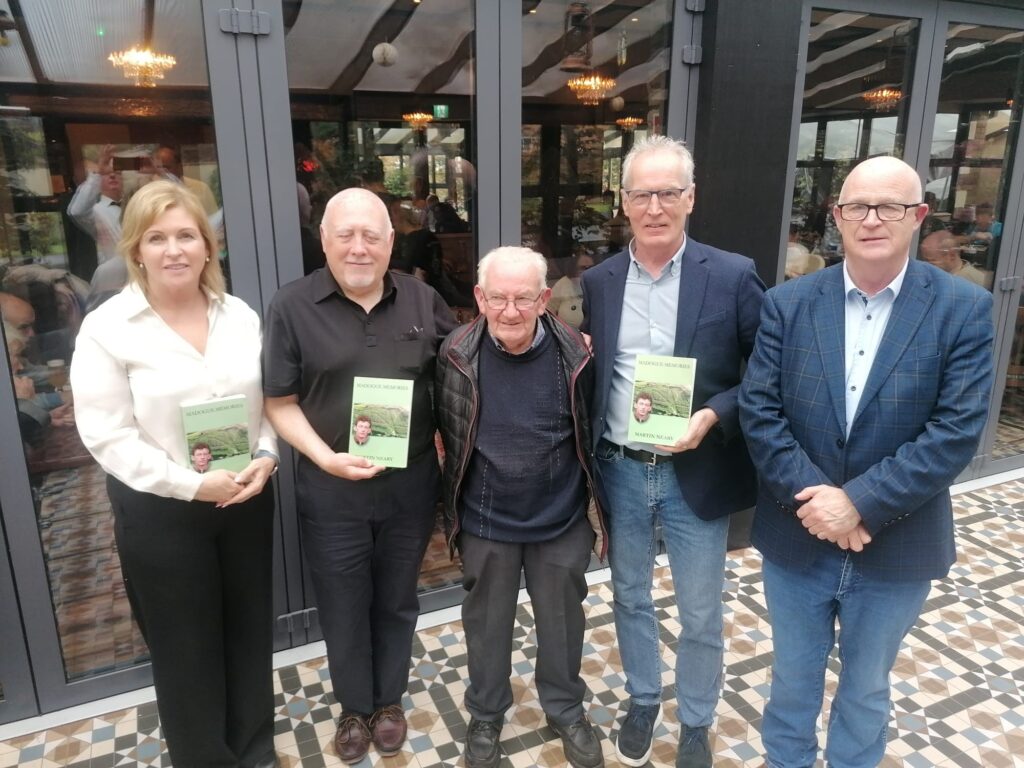

Rose Conway-Walsh TD, Danny Morrison, Martin Neary, Gerry Kelly MLA, and Sinn Féin Councillor Gerry Murray

Martin was an only child and when he was five his father, Martin Snr, a former IRA veteran, and an atheist, died. From his bedroom the child hears the Rosary being said for the first time and thinks that his father would not have approved of his mother sending for the priest, nor of the subsequent Requiem Mass which is also the first time Martin has darkened the doors of a chapel. On the subject of death, he is now quite philosophical: ‘Summer follows winter and bad weather follows good weather.’

He only hears that there is a thing called ‘religion’ when he starts school—‘the church was in charge of everything’—and is introduced to the catechism.

‘[S]eeing that the teachers and priests and shopkeepers said it was true I believed them.’ Hilariously, he concludes that after learning how to be good, ‘I knew that all my friends and people I liked were going to hell . . . I had heard the guards in Charlestown (there were about eight of them) were heavy drinkers so they hadn’t a hope … I was brain-washed for the next fifteen years.’

In his childhood days, which took in the Emergency (WWII) and rationing, there were few cars on the roads. Indeed, his aunt is terrified the first time she is a passenger in one. (The first time he is on a boat is going to England for seasonal work in his early twenties and it is also in England that he experiences using a lift or the first time.) He remembers his granny smoking a pipe; the carpenter and blacksmith building a wheel for a barrow; seeing a tomato for the first time; and remembers that he first prize in the school high jump was a (quite useless) holy picture!

‘[E]very thing is new to a child and that may be why we remember so much from our childhood.’

OASIS

Among his neighbours was Kate Gallagher whose husband John ‘may have been delicate because he used to eat town bread. When Kate would invite someone in for tea she would say, “Come in and I will give you a piece of John’s loaf.”’

Kate’s grandniece, Maggie O’Brien, came to live with her before she was married. Maggie is the grandmother of Noel and Liam Gallagher of Oasis.

Irish lives are marred by the sadness of emigration, the emigrant always hopeful that someday the native might return to the homeplace, But as Gerry Murray writes: ‘very few returned, some were never heard of again.’ Big families of up to ten or twelve children saw all but one son or daughter depart for the USA or England, leaving that one person behind to till the land—and even then still relying on remittances in that precious registered letter which kept the wolf from the door.

When Martin surveys his surroundings now he sees lots of new houses but from every ruin and fallen gable wall this man, this recorder of times past, remembers the folk who were born and lived here, ‘most of whom are now long dead, but were a mighty force in their time.’ He can trace his paternal family roots back to 1818, a time of ongoing agrarian unrest when the Ribbonmen defended tenant farmers and rural workers.

As an only child he was expected to take over the farm but to support it he also had to do seasonal work in England, often for four months each winter, in a sugar beet factory, work he liked and which despite long shifts he found ‘easier’ than a long day in the bog or long days’ hay making, but he was never tempted to stay. He was amazed to see over hundreds of cows grazing in fields in Shropshire whereas in Mayo it would be just five or six beasts. Back home, in Charlestown, the people would stand around and gossip, whereas ‘in Wellington everyone was in a hurry.’

While he was away a neighbour would cut a bank of turf for his elderly mother and others would look after the hay, potatoes and oats.

He also joined the old FCA (An Fórsa Cosanta Áitiúil) which was later integrated into the Army Reserve but back then was a local defence force which could be called upon to serve during emergencies. He enjoyed its esprit de corp and made many friends. His interest in politics dates from the 1950s when he learnt of partition and followed the election campaigns of political prisoners in Fermanagh and South Tyrone and Mid-Ulster who, upon being successfully elected, were immediately unseated by unionist electoral courts.

Martin Neary carries an aura of immense peace and ease, a man with no regrets, which is a rare thing.

‘I settled into life as a full-time farmer, following the rhythms of the year. Between the fields I had walked as a child and those I had bought and reclaimed, I knew every inch of my farm. I knew that I was doing the best I could do with it. I took good care of my cattle and they provided me with a livelihood. I had good neighbours and friends. Although the work was hard and the hours long there was a contentment and an independence which might not have been available in a different way of life.’

We are so glad he stayed and chronicled his and his Mayo people’s journey through the quotidian of their not insignificant histories!