Fr Des Wilson died yesterday at the age of ninety four. I saw him for the last time two weeks ago at Nazareth House Care Village. He was very frail and his voice was a whisper. But with him was Janet Cush, one of many from the Springhill and Ballymurphy community who sat by his side in vigil, daily, and kept him company, out of love and loyalty to a man and priest who devoted his life as a witness to oppressed people and served them like no other.

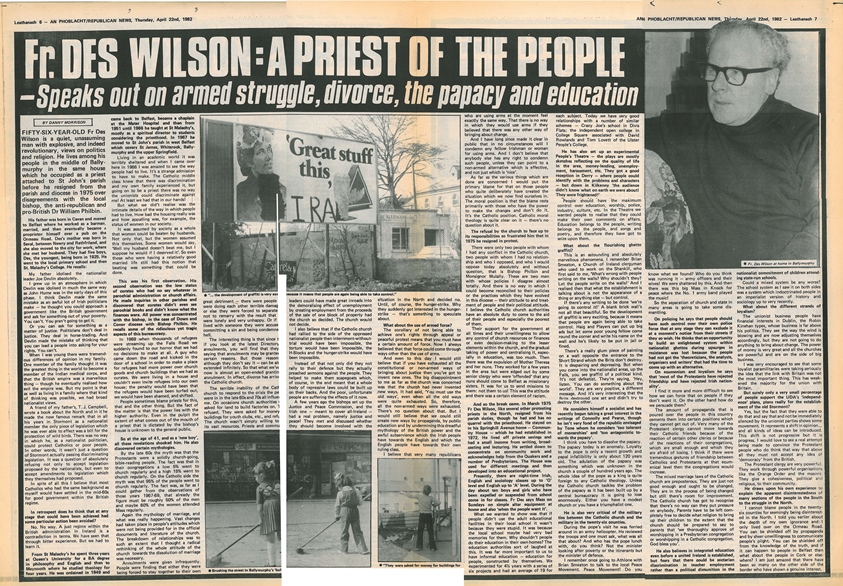

I told Des about the great interview he gave me thirty seven years ago when I was editor of An Phoblacht/Republican News, and he asked me to send it to him which I did the following day.

Even now, reading it, you can see how advanced he was and, of course, his politics were always evolving. Here is the interview which was published on 22nd April, 1982.

-oo0oo-

FIFTY-SIX-YEAR-OLD Fr Des Wilson is a quiet, unassuming man with explosive, and indeed revolutionary, views on politics and religion. He lives among his people in the middle of Ballymurphy in the same house which he occupied as a priest attached to St John’s parish before he resigned from the parish and diocese in 1975 over disagreements with the local bishop, the anti-republican and pro-British Dr William Philbin.

His father was born in Cavan and moved to Belfast where he worked as a barman, married, and then eventually became a proprietor himself over a pub on the Ormeau Road. Des’s mother was born in Saval, between Newry and Rathfriland, and she also moved to the city for work, where she met her husband. They had five boys, Des, the youngest, being born in 1925. He went to the local primary school and then St Malachy’s College. He recalls:

“My father idolised the nationalist leader Joe Devlin, absolutely.

“I grew up in an atmosphere in which Devlin was idolised in much the same way as John Hume was in the early days of this phase. I think Devlin made the same mistake as an awful lot of Irish politicians make – he thought you could approach a government like the British government and ask for something out of your poverty. You can’t. You aren’t going to get it.

“Or, you can ask for something as a matter of justice. Politicians don’t deal in justice. They deal in horse-trading. And Devlin made the mistake of thinking that you can lead a people into asking for your rights. You can’t.

“When I was young there were tremendous differences of opinion in my family. One member of the family thought it was the greatest thing in the world to become a member of the Indian Medical Corps, and that the British Empire was a marvellous thing – though he eventually realised how evil the empire was. But my point is that as well as living in a family where that kind of thinking was possible, we had broad nationalist views.

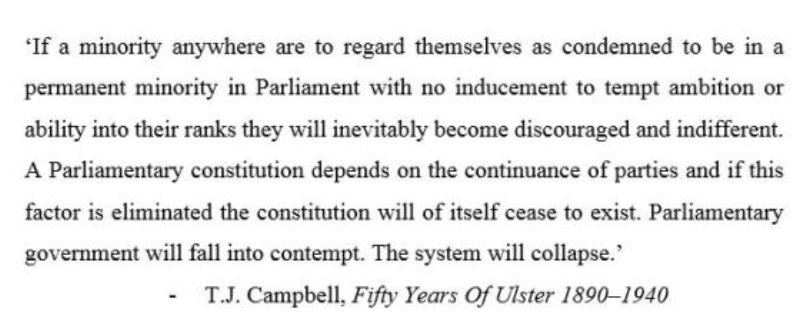

“A friend of my father’s, T. J. Campbell, wrote a book about the North and in it he made the now famous remark that in all his years in Stormont as a nationalist member the only piece of legislation which he was ever able to effect was a bill for the protection of wild birds. There was no way in which he, as a nationalist politician, could protect Catholics or poor people. In other words, it wasn’t just a question of Stormont actually passing discriminating legislation. It was a question of absolutely refusing not only to accept legislation proposed by the nationalists, but even to accept amendments to legislation which they themselves had proposed.

“In spite of all this I believe that most Catholics who had the same background as myself would have settled in the mid-60s for good government within the British regime.”

In retrospect does he think that at any stage that could have been achieved had some particular action been avoided?

“No. No way. A just regime within the British administration in Ireland is a contradiction in terms. We have seen that through bitter experience. But we had to learn it.”

From St Malachy’s he spent three years at Queens University for a BA degree in Philosophy and English and then to Maynooth where he studied theology for four years. He was ordained in 1949 and came back to Belfast, became a chaplain at the Mater Hospital, and then from 1951 until 1966 he taught at St Malachy’s, mostly as a spiritual director to students considering the priesthood. In 1967 he moved to St John’s parish in West Belfast which covers St James, Whiterock, Ballymurphy and the Upper Springfield.

“Living in an academic world it was terribly sheltered and when I came over here in 1966 I was amazed to see the way people had to live. It’s a strange admission to have to make. The Catholic middle class knew that there was discrimination and my own family experienced it, but going on to be a priest there was no way the unionists could discriminate against me! At least we had that in our hands!

“But what we didn’t realise was the intimate details of the way in which people had to live. How bad the housing really was and how appalling was, for example, the status of women in our society.

“It was assumed by society as a whole that women could be beaten by husbands. Not only that, but the women assumed this themselves. Some women would say, ‘Well, my husband doesn’t beat me, but I suppose he would if I deserved it.’ So, even those who were having a relatively good married life still had this notion that beating was something that could be done.”

This was his first observation. His second observation was the low status of curates who had no say whatever in parochial administration or church affairs. He made inquiries in other parishes and discovered that curates didn’t even see the parochial books and didn’t know what the finances were. All power was concentrated with the bishop, in the case of Down and Conor diocese with Bishop Philbin. He recalls some of the ridiculous yet tragic aspects of this bureaucracy.

“In 1969, when thousands of refugees were streaming up the Falls Road, we suddenly found to our horror that we had no decisions to make at all. A guy who came down the road and kicked in the door of a school in order to make a place for refugees had more power over church goods and church buildings that we had as curates. We were living in a house and couldn’t even invite refugees into our own house; the penalty would have been that the refugees would have been turfed out, we would have been shamed, and shifted.

“People sometimes blame priests for this, that and the other thing. But the fact of the matter is that the power lies with the higher authority. Even in the pulpit the extent of what comes out of the mouth of a priest that is dictated by the bishop’s house is unknown to the general public.”

So, at the age of forty one, and as a ‘new boy’, all these revelations shocked him. He also discovered certain mythologies.

“By the late 60s the myth was that the Protestants were a solidly church-going, bible-reading people. The fact was that in their congregations a low 5% went to church regularly and a high 15% went to church regularly. On the Catholic side the myth was that 95% of the people went to church regularly. The fact was, as far as I could gather from the observations of those years, 1967-69, that already the figure must be roughly 50% of the men and maybe 60% of the women attended Mass regularly.

“Again, the mythology of marriage, and what was really happening. Vast changes had taken place in people’s attitudes which were not being provided for in the official documents and literature of the church. The breakdown of relationships was to such an extent that I thought a radical rethinking of the whole attitude of the church towards the dissolution of marriage was necessary.

“Annulments were given infrequently. People were finding that either they were being forced to stay together, to their own great detriment – there were people who were doing each other terrible damage, or else they were forced to separate but not to remarry, with the result that they were lonely and very unhappy. Or if they lived with someone they were accused of committing a sin and being condemned to hell.

“The interesting thing is that since then, if you look at the latest Directory of annulments, you will find that they are saying that annulments may be granted for certain reasons. But those reasons, although they don’t say it – can be almost extended infinitely. So that what we’ve got now is almost an open-ended granting of annulment. In effect, divorce has arrived in the Catholic Church.

“The terrible inability of the Catholic Church to respond to the crisis the people were in, in the late 60s and 70s, all influenced me. On occasions church authorities were asked for land to build factories on. They refused. They were asked for money for buildings for youth clubs, etc., and refused. The church wasn’t simply willing to use its vast resources. Priests and community leaders could have made great inroads into the demoralising effect of unemployment by creating employment from the proceeds of the sale of one block of property had the church so decided. The church would not decide.

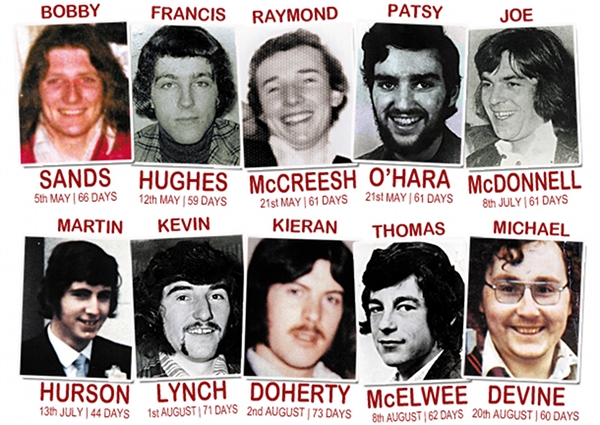

“I also believe that if the Catholic Church had rallied to the side of the oppressed nationalist people then internment-without-trail would have been impossible, the torture would have been impossible, the H-Blocks and the hunger strike would have been impossible.

“Instead of that, not only did they not rally to their defence but they actually preached sermons against the people. They helped to make them scapegoats which, of course, in the end meant that a whole body of repressive laws could be built up on their backs. And the poor, unfortunate people are suffering the effects of it now.

“A few years ago the bishops set up the Justice and Peace Commission, and the Irish one – meant to cover all-Ireland – had a real problem, namely justice and peace! They met and discussed whether they should become involved with the situation in the North and decided, ‘No’. Until, of course, the hunger strike. Why they suddenly got interested in the hunger strike – that’s something to speculate about.”

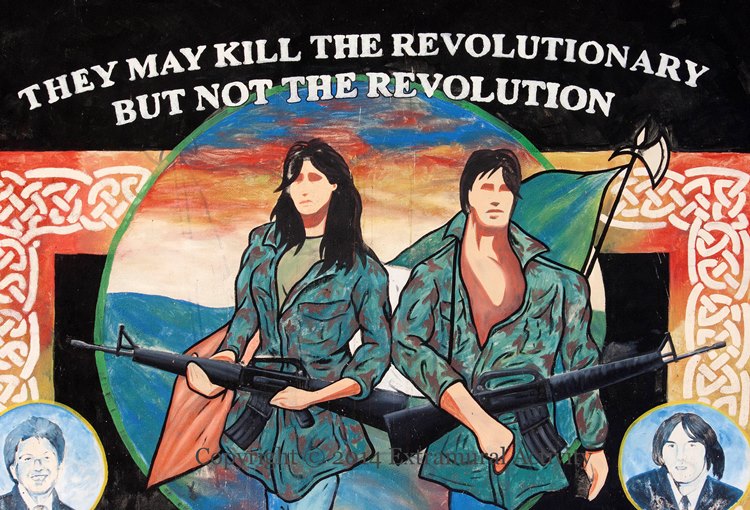

What about the use of armed force?

“The corollary of not being able to achieve one’s rights through appeal or peaceful protest means that you must have a certain amount of force. Now I always believed that that force could come through ways other than the use of arms.

“And even to this day I would still believe that if you have exhausted all the constitutional or non-armed ways of bringing about justice then you’ve got to invent new ones. The big disappointment to me, as far as the church was concerned, was that the church had never invented new ways. It had said. ‘You must use the old ways’, even when all the old ways were quite exhausted. So, therefore, all the non-armed ways were exhausted. There’s no question about that. But I would still believe that we could still create new ways by propaganda, by public education and by undermining this dreadful mythology of the British power and the awful subservience which the Irish people have towards the English and which the English people have towards their own ruling class.

“I believe that very many republicans, who are using arms at the moment, feel exactly the same way. That there is no way in which they would use arms if they believed that there was any other way of bringing about change.

“And I have long since made it clear in public that in no circumstances will I condemn any fellow Irish man or woman for using arms. And I don’t believe that anybody else has any right to condemn such people, unless they can point to a non-armed alternative which is effective, and not just which is ‘nice’.

“As far as the various things which are done are concerned I would put the primary blame for that on those people who quite deliberately have created the situation which we now find ourselves in. The moral position is that the blame rests primarily with those who have the power to make the changes and don’t do it. It’s the Catholic position. Catholic moral theology is quite clear on it – there’s no question about it.

The refusal by the church to face up to its responsibilities so frustrated him that in 1975 he resigned in protest.

“There were only two people with whom I had any conflict in the Catholic Church; two people with whom I had no relationship and who I opposed, and who I would oppose today absolutely and without questions – that is, Bishop Philbin and Monsignor Mulally. These are two men with whose policies I disagree almost totally. And there is no way in which I could become reconciled to their policies or the practices which they have evolved in this diocese – their attitude to and treatment of people and their political attitude. I believe the Catholic Church authorities have an absolute duty to come to the aid of their people and especially the poorest of them.

“Their support for the government at all times and their unwillingness to allow any control of church resources of finances or even decision-making to the lesser elements within the church, and the gradual taking of power and centralising it, especially in education, was too much. Then there was the expulsion of Mother Teresa and her nuns. They worked for a few years in the area but were edged out by some senior clergy who were ‘offended’ that any nuns should come to Belfast as missionary sisters. It was for us to send missions to them: not them to us! This was the attitude and there was a certain element of racism.”

And so the break came. In March 1975 Fr Des Wilson, like several other protesting priests in the North, resigned from his parish duties, though he had and has no quarrel with the priesthood. He stayed on in his Springhill Avenue home – Community House – which he had established in 1972. He lived off private savings and had a small income from writing, broadcasting and lecturing. He settled down to concentrate on community work and acknowledges help from the Quakers and a number of Presbyterians. The House was used for different meetings and then developed into an educational project.

Presently, there are night-time Irish, English and Sociology classes up to 0-Level and English up to A-Level. During the day about ten boys and girls who have been expelled or suspended from school come in for classes. Fr Des says Mass on Sundays on simple altar equipment at home and also “when the people want it.”

“What we wanted to show was that if people don’t use the educational facilities in their local school it wasn’t because they were stupid. It was because the local school maybe had very bad memories for them. Why shouldn’t people do their education in their own homes? The education authorities sort of laughed at this. It was far more important to us to have informal education – education for people, constructed by themselves. We experimented for four-and-a-half years with a series of six projects and had an average of nineteen for each subject. Today we have very good relationships with a number of similar schemes – Crazy Joe’s school in Divis Flats; the independent open college in College Square with David Rowlands and Tom Lovett of the Ulster People’s College.”

He has also set up an experimental People’s Theatre – the plays are mostly sketches reflecting on the quality of life in the area, money-lending, unemployment, harassment, etc. They got a good reception in Derry – where people could identify with the problems and characters – but down in Kilkenny “the audience didn’t know what on earth we were about! They were frightened!”

“People should have the maximum control over education, worship, police, industry, culture, etc. In the Theatre we wanted people to realise that they could make their own comments on affairs. Education belongs to the people, writing belongs to the people, and songs and poetry, and therefore they have got to seize upon them.”

What about the flourishing ghetto graffiti?

“This is an astounding and absolutely marvellous phenomena. I remember Brian Smeaton, a Church of Ireland clergyman who used to work on the Shankill, who first said to me: ‘What’s wrong with people writing on the walls? Why shouldn’t they? Let the people write on the walls!’ And I realised then that what the establishment is talking about is not the appearance of a thing or anything else – but control.

“If there’s any writing to be done, ‘we’re going to control it!’ A blank brick wall’s not all that beautiful. So the development of graffiti is very exciting, because it means that people are again being able to take control. Haig and Players can put up big ads but let some poor young fellow come round the corner and write his name on the wall and he’s likely to be put in jail or fined.

“There’s a really glum piece of painting on a wall opposite the entrance to Short Strand which the Brits don’t destroy. It is despairing and depressing. But when you come into the nationalist areas, up the Falls, you see graffiti of a political kind. It’s not defeatist. They’re saying, ‘Hey, listen. You can do something about the world.’ They are very positive, a different message. And it’s very interesting that the Brits destroyed one set and didn’t try to destroy the other.”

He considers himself a socialist and has recently begun taking a great interest in the writings of Connolly and Pearse, though he isn’t very fond of the republic envisaged by Tone whom he considers ‘too tolerant of monarchies’ and ‘too antagonistic towards the papacy’.

“I think you have to dissolve the papacy. The papacy today is an anomaly. Loyalty to the pope is only a recent growth and papal infallibility is only about one hundred and twenty years old. The adulation of the papacy was something which was unknown in the church a couple of hundred years ago. The whole idea of the pope as a king is quite foreign to any Catholic theology. Unless the Catholic Church tackles the problem of the papacy as it has been built up by a central bureaucracy it is going to lose enormously. Either you have a modest church or you have a triumphalist one.”

He is also very critical of the military ties between the Catholic Church and the military in the Twenty-Six Counties.

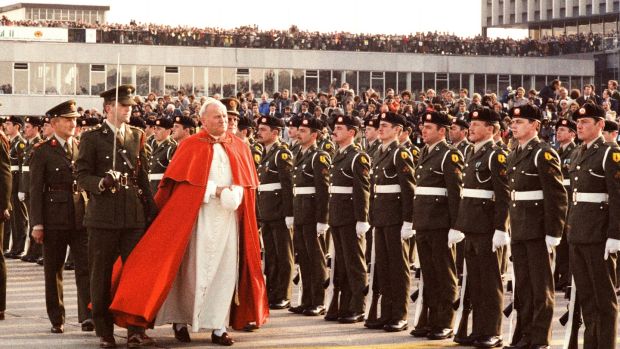

“During the pope’s visit he was ferried around in an army helicopter. He reviewed the troops and one must ask, what was that all about? And who has the pope lunch with, do you think? Not the minister looking after poverty or the itinerants but the minister of defence.

“I remember once going to Athlone with Brian Smeaton to talk to the local Peace Movement. Peace Movement! Do you know what we found? Who do you think was running it – army officers and their wives! We were shattered by this. And then there was this big Mass in Knock for peace where the Number 1 army bank played the music!

“So, the separation of church and state in many areas is going to take some dismantling.”

On policing he says that people should have such control over their own police force that at any stage they can exclude it at a moment’s notice from their streets if they so wish. He thinks that an opportunity to build an enlightened system within nationalist ghettoes during upsurges in resistance was lost because the people had not got the ‘theoreticians, the analysts, organisers and writers’ that had the time to come up with an alternative.

On ecumenism and loyalism he says that ‘most of the Protestants have rejected friendship and have rejected Irish nationality.’

“I find it more and more difficult to see how we can force that on people if they don’t want it. On the other hand, how do we persuade them?

“The amount of propaganda that is poured over the people in this country cements them into certain positions which they cannot get out of. Very many of the Protestant clergy cannot move towards their Catholic friends because of the reaction of certain other clerics or because of the reactions of their congregations, which are small enough and which they are afraid of losing. I think if there were tremendous gestures of friendship between Catholics and Protestants at that ecumenical level then the congregations would increase.

“The mixed marriage laws of the Catholic Church are preposterous. They are just not good enough and ought to be changed. They are in the process of being changed but still there’s room for improvement. The Catholic Church has got to recognise that there’s no way can they put pressure on anybody. Parents have to be left completely free to decide what religion to bring up their children to the extent that the church should be prepared to say to parents that ‘we thoroughly approve of worshipping in a Presbyterian congregation or worshipping in a Catholic congregation. God bless you.’”

He also believes in integrated education even before a united Ireland is established, but fears that there could be sectarian discrimination in teacher employment rather than a political diminution in the nationalist commitment of children attending state-run schools.

“Could a mixed system be any worse? The school system as I saw it on both sides was a system which indoctrinated people in an imperialist version of history and sociology up to very recently.”

What about the different strands of loyalism?

“The unionist business people have financial interests in Dublin, the Robin Kinehan types, whose business is far above his politics. They see the way the wind is blowing and are now adjusting themselves accordingly, but they are not going to do anything to bring about change. The power of money is very great and all the churches are powerful and are on the side of big business.

“I was very encouraged to see that some loyalist paramilitaries were taking seriously the idea that the link with Britain was not the most important thing. This has weakened the majority for the union with Britain.”

But surely only a very small percentage of people support the UDA’s ‘independence’ plans, plans really for the establishment of the old Stormont?

“Yes, but the fact that they were able to do that and say that and not be immediately silenced by the unionist parties shows some movement. It represents a shift in opinion… and all kinds of ideas can be introduced. The shift is not progressive but it is progress. I would love to see a real attempt being made to convince the Protestant people who do think that way, that above all they must not accept any idea of ‘democracy’ from the British.

“The Protestant clergy are very powerful. They work through powerful organisations like the Orange Order and the masons. They give a cohesiveness, political and religious, to their community.”

He draws upon his own experience to explain the apparent disinterestedness of many sections of the people in the South to the struggle in the North.

“I cannot blame the people in the Twenty-Six Counties for seemingly being disinterested in the North. I told you earlier about the depth of my ignorance and I only lived over on the Ormeau Road. You can be shielded off by propaganda and by sheer unwillingness to communicate people’s plight. You can be shielded off from the knowledge of the truth, and if it can happen to people in Belfast then what about the people in Cork or elsewhere? I am just amazed that there have been so many on the other side of the border who have shown a genuine interest.”