LAST night I finished Cónal Creedon’s Begotten Not Made, a novel which at one time would have got him excommunicated! It is multi-layered, funny and touching, at times madcap or magic realist, quintessential story-telling, and has a wonderful and satisfying ending.

It’s about the unrequited love between Brother Scully and Sister Claire, a novitiate in the convent across the valley from his monastery in Cork city.

That spiritual affair began on the night in 1970 that Dana won the Eurovision Song Contest, and it lasts for almost fifty years.

Scully, an excitable young man, doubtful cleric and theological sleuth who for two years has dedicated his spare time and nights to studying ancient texts, comes to conclude a heretical theory that John the Baptist and his cousin Jesus Christ were both sired by Herod the Great – and not God the Father! Bedeviled by his ‘discovery’, he is less than discreet with whom he tells.

“There’s no mystery in the story of Christ. It’s all about paternity, inheritance and family. It’s all about a father who had rejected his son at birth, and a son’s lifelong struggle for his father’s acceptance. It’s all about an illegitimate boy’s struggle to regain his birthright.”

Claire, whose imagination is both ripe and fertile, is bewildered and has her faith thrown into disarray, as she empathises with the story of the alternative history of Christ while they make tea together out in the kitchen for the nuns who are visiting the monastery. The nuns are there because the monastery has, despite the resistance of the deputy-head, just rented a colour television and they are cheering on Dana against the Brits’ entrant, Mary Hopkin, singing, Knock, Knock, Who’s There.

A mistake on the naïve Scully’s part during a subsequent investigation into his colloquy with the Sister results in him being banned from ever seeing her again. But their correspondence continues: Scully and Claire send a signal to each other every morning at dawn by quickly switching their bedroom light off and on.

That one single act of devotion gives Scully the courage to live out his chaste life.

But not all is how it seems. And there is a sting in this tail.

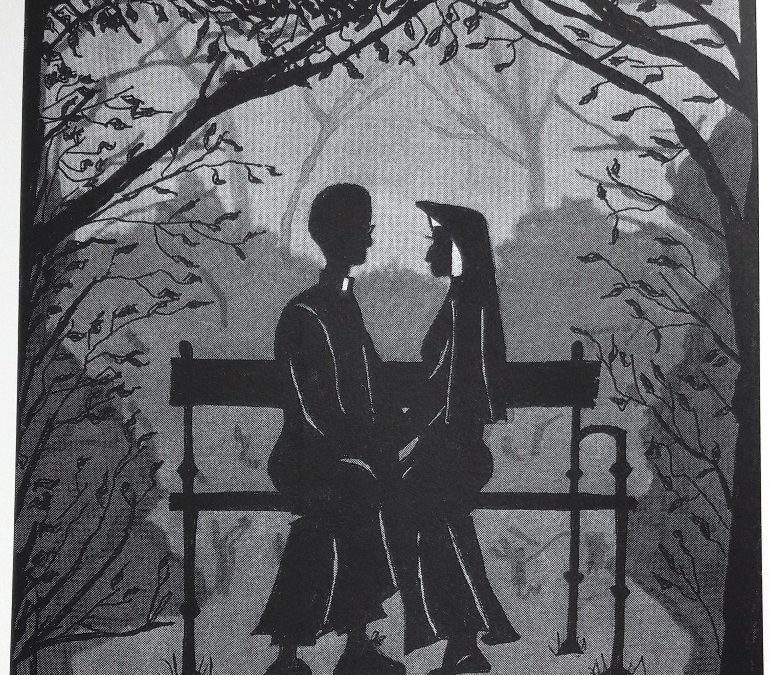

CÓNAL has drawn a number of fine pen and ink illustrations to accompany the story which lends a charmingly quaint feeling to the rich reading experience.

There are several poignant moments in the novel, the most moving of which is when towards the end of their hour or two together in 1970, in the garden, Scully and Claire are faced with a crucial decision.

And that predicament, upon which their fates turned, reminded me of that great Cavafy poem, Che fece… il gran rifiuto (The Great Refusal):

For some people the day comes

when they have to declare the great Yes

or the great No. It’s clear at once who has the Yes

ready within him; and saying it,

he goes forward in honour and self-assurance.

He who refuses does not repent. Asked again,

he would still say no. Yet that no – the right no –

undermines him all his life.