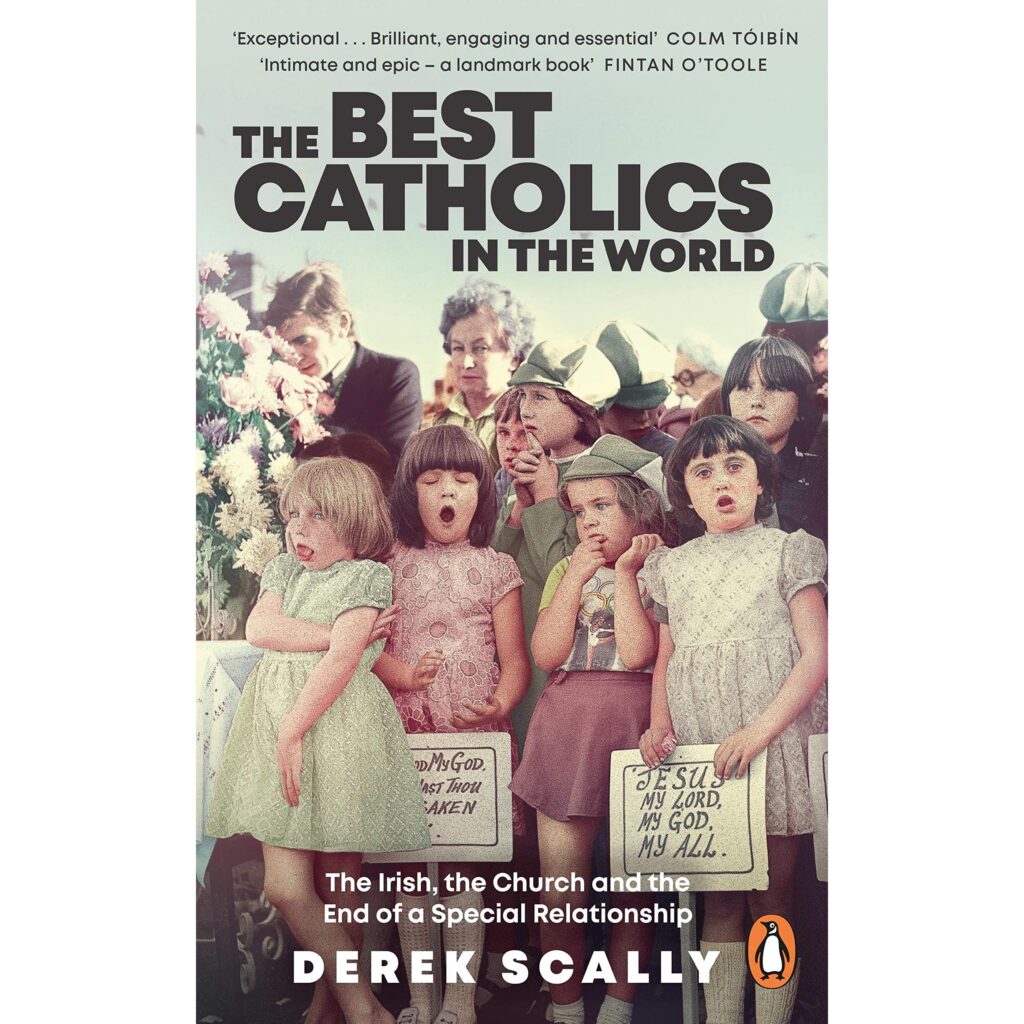

My review of Derek Scally’s book, The Best Catholics in the World was published in last Saturday’s Irish Examiner, 9 October. Here it is:

That old Latin phrase, Corruptio optimi pessima (the corruption of the best is the worst of all) explains the magnitude of the anger and disillusionment of the former laity as the dam burst and a flood of seemingly endless child sex abuse scandals engulfed the once unassailable Catholic Church in Ireland. The attempted cover-ups, the aversion to settling compensation claims, resistance to discovery of records, and state collusion, only compounded the crimes.

In the words of the 2009 Murphy Commission a major preoccupation of the hierarchy was ‘the maintenance of secrecy, the avoidance of scandal, the protection of the reputation of the church, and the preservations of its assets.’

This book by Derek Scally (Berlin correspondent for the Irish Times) makes compelling reading for the breadth of its research, including a potted history of Christianity in Ireland, its detailing of the rise of the hierarchy and its relationship with the Vatican and British power in this country (at whose hands the faithful suffered immeasurably), but also for the very personal narrative that runs alongside his various theses.

Visiting Ireland from Germany, where he has lived for twenty years, and intrigued by how that nation coped with both its Nazi and Stasi histories through Vergangenheitsbewältigung (the attempt to analyse, digest and learn to live with the past), Scally journeys his way through the terminal decline in religiosity, beginning with the innocence of his time as an altar boy in his old parish, St Monica’s in Edenmore, Raheny, in Dublin.

A priest there, Fr McGennis, was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment for a historic sex abuse case dating back to 1960. How could such a pious man of the collar, renowned for his affinity to his flock and his long homilies (“If you want to understand the concept of eternity, go sit through one of his sermons”), be such a monster? McGennis took advantage of the children of the poorer, deprived families from the housing estates, took them for drives, took girls swimming and let children play in his house.

It turns out there were complaints from those brave enough to stand up to this totalitarian, predatory and meddling institution, but they were dismissed and McGennis had free rein for another ten years. And this leads to another uncomfortable truth about responsibility. For example, it was parents out of misplaced shame and deference to the hypocritical mores of Catholic society who discarded their daughters into the laundries where they were demonised because they had sex and fell pregnant or were the victims of incest and abuse.

Although Scally says that ‘knowing something’ is ‘not the same as being able to change it’, it still stands as a devastating indictment of the public’s responsibility in ‘the sliding scale between innocence and complicity.’ In 1999 the writer Dermot Bolger said, ‘in truth, most Irish people felt the inmates got what they deserved.’

The problem can be traced back to the founding of the fledgling state, after British withdrawal, with successive governments outsourcing their social services and handing over education and health to religious orders. The Catholic Church exercised authority as a shadow power with a crozier in one hand and the Bible in the other.

One of the most excruciating parts of the book deals with the rise and downfall of Cardinal Sean Brady whom Scally interviewed several times. In 1975 Brady was part of a secret investigation into the paedophile Fr Brendan Smyth which involved questioning a fourteen-year-old boy alone and swearing him to silence over his allegations. Smyth’s punishment? He was stripped of his right to hear confession—then he went on to abuse children for another sixteen years. Scally surmises that Brady, though not involved in how his superiors disciplined Smyth, behaved the way he did for two reasons, which included an eye to future ambition.

‘Conflicted between loyalty to the church and the needs of an innocent child’ he chose to protect the reputation of the church.

This book is harrowing. Yet despite all the abuse stories, the huge decline in attendance and religiosity, the slump in ordinations, and the mocking of the Catholic Church in an ascendant, confident, prospering young secular society, Scally, a self-confessed ‘grappling Irish Catholic’, reports the belief of some adherents that we are living in ‘an exciting time’, on the brink of establishing ‘a new model of church’.

Ooom. It’s with O’Leary, I think.