‘Oh my God! ’E looks like a toad!’ were the first words said by Brian Blessed’s mother just after she had given birth. ‘’E looks as if ’e’s been in the ring with Joe Louis!’

I have always admired Brian Blessed from his earliest days in ‘Z Cars’ in 1962 which I watched from the age of nine, but I thought he was absolutely brilliant as Augustus in the BBC series, ‘I, Claudius’. A few weeks ago I saw him chair ‘Have I Got News For You’ in his normal way: that is, he was as mad as a hatter, and I immediately went on Green Metropolis and ordered the first part of his memoir The Dynamite Kid. He has such joie de vivre and even his rant about Gerry Adams on ‘Have I Got News’ I found hilarious.

I loved The Dynamite Kid, its tenderness, its descriptiveness about the pastoral beauty of the English countryside, his love of music and adventure, his gaucheness with women. It is a warm and honest story about growing up the son of a Yorkshire miner (his uncle was killed in a mining accident) and being frustrated at wanting to get to drama school; having to work as a coffin maker; having to work as a plasterer by day to pay for voice classes and then having to do two years national service before going to Bristol Old Vic Theatre School where his friend was Patrick Stewart. (Both were to act in ‘I, Claudius’.)

As a kid in his gang he played the role of Vultan, King of the Hawkmen from Flash Gordon, and then thirty years later he actually plays that part in a film! An adventurer as soon as he got out of nappies, he loved trains, raiding orchards or carrying a dead cat around as a talisman even as it rotted. He was so enthused with boxing that when only seven years old he cycled eight miles to watch Bruce Woodcock, the English heavyweight boxer, train. Blessed told true stories but adults thought he was a pathological liar.

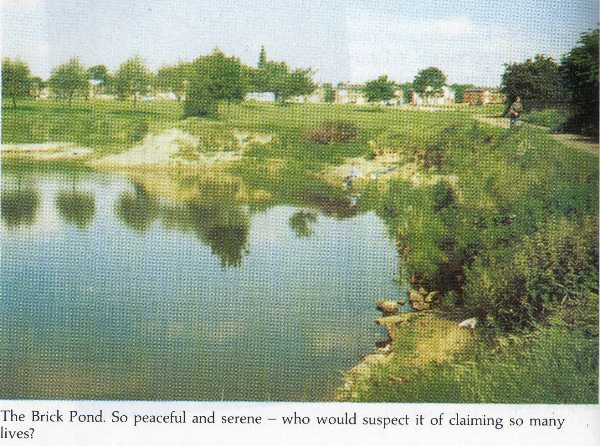

There is a real sadness about the chapter, ‘The Brick Pond’, which reminded me of the death of young Stephen Duignam in our street when he was about six or seven. I suppose everyone has a poignant memory of the death of a young friend. We had guiders and ginger-haired, freckled-face Stephen was playing on his little wooden board at the top of Iveagh Parade. A neighbour reversing a van accidentally struck Stephen. Stephen’s injuries weren’t serious but it was while he was in hospital that the doctors, running blood tests regarding his allergies to antibiotics, discovered he had leukemia and we never saw Stephen again until his little body was returned to us in a small coffin to 37 Iveagh Parade. Blessed tells of how he led his gang to the pond to see dead toads and that one of the boys, Tank, fell in and drowned before their eyes and though they tried they could not save him.

The death of Tank was the end of Blessed’s childhood.

He loved boxing and was due to represent Highgate Junior Mixed School but first had an exam to do. The exam invigilator was flabbergasted when Blessed announced with great confidence after twenty minutes that he had finished. He was so impatient to get outside and warm up for the fight that he had filled his exam papers with sketches of dinosaurs and noughts and crosses! He ended up among the hopeless cases, ‘the dunce class’, ‘the wooden tops’ but was subsequently saved by a teacher with drive and determination to make something of them, Mrs Brown.

She taught them Shakespeare, Wilde, Keats and Wordsworth, the history of the Greeks, the story of Odysseus. She was transformational and when she eventually left, the class was heart-broken.

His art teacher, Mr Donaldson, and his form master, Mr Quament, were also influential. In the school play Blessed acted Rumpelstiltskin. He caught the bug and his talent as an actor was spotted immediately. The next day Mr Donaldson asked the class, “What happened yesterday in the play?”

One pupil joked that Blessed was funny but Mr Donaldson became serious and continued:

“When the Miller’s daughter finally guessed his name, during his mad laughter, what did Blessed do?… He paused! He paused! Probably the most important effect in dramatic art. That’s what he did, he paused!”

In 1950 he went to the Second World Peace Congress in Sheffield to see and hear Paul Robeson, ‘the black ambassador of freedom’. But before that he bumped into a guy claiming to be Picasso.

Blessed said: “You don’t look like Picasso! If you’re Picasso, let’s see you draw something… If you’re from Spain, how much did it cost you to come here?”

It is, actually, Picasso and he draws something on a piece of paper – a Dove of Peace. Blessed asks him why the dove looked so unfinished at the bottom of its body.

“I am trying to show zat someone is holding zee dove in zeir ’and.” Picasso added his signature which Blessed said looked like algebra.

(I remember the day Picasso died in April 1973 because I noted it in my Long Kesh jail diary and how the sky, spotted with tiny black clouds from the direction of the lough, reminded me of the coat of a dalmatian hound.Who did I say this to? Who was in the exercise yard? Where are they now?)

After the concert Blessed bluffed his way backstage and got talking to Paul Robeson and complained that he hadn’t sang ‘Ah Still Suits Me’. So Robeson sets Blessed on his knee and they do the duet together with Blessed singing the woman’s part: “Does yer ever wash the dishes, does yer do the things a wishes, does yer do ’em – no you won’t!”

Back at school Blessed – a late developer – was learning rapidly. After acting in a school production of Macbeth he just knew he wanted to become an actor but life (and is there, ultimately, something amiss about that?) got in the way.

Although a powerful figure he was bullied and teased by fellow plasterers about his acting and, in particular, one bad review. He lost his temper and physically attacked a labourer. But he was also sensitive and fell into a long state of depression; began to doubt himself, and his mental condition deteriorated.

He writes honestly about this period, his recovery but also about his haughtiness and how one who is admired, half-famous, half-successful, can become quite egotistical.

This memoir is a real gem where a great actor opens up to us his very soul and conscience, his strength and foibles, his humour, his courage, his humanity.