I wrote a feature for An Phoblacht in memory of the South African journalist David Beresford who died last week after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. David, who wrote for the Guardian, was also the author of Ten Men Dead. Here is my piece followed by the chapter he wrote for the book of essays I edited in 2006, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1981 hunger strike.

I can’t remember when or where I first met David Beresford but it was in the late 1970s after he had been posted by the Guardian to Belfast to replace Anne McHardy, another brilliant and honest journalist of that period.

McHardy was later to write about a government dinner party in the Europa Hotel when she learnt that her phone was being bugged. Next to her a drunk NIO press officer, Tommy Roberts, revealed that he and the then Secretary of State, Roy Mason, had listened to the tapes of a row she had had with her fiancé over which of them had left the freezer unplugged the last time she was in London. Another press officer leaned over and said, “That boyfriend of yours doesn’t like you being here.”

NIO Press Officer Roberts was also a colonel in the UDR. Yes, that was the way things were. A UDR man was the NIO’s press officer. Is it any wonder.

David Beresford, Anne’s replacement, was quietly spoken as if every word he had to say was deliberate and considered. He also had a quiet laugh. But what struck me was his sincerity.

It was Tom Hartley, manager of the Republican Press Centre, who told me I should meet him. Tom had a knack for spotting the more objective, fair-minded, among the press.

So, the three of us went for a drink around teatime one Thursday in Walsh’s Bar at the bottom of Clonard Street, with a fresh edition of Republican News (which had yet to merge with An Phoblacht). David wanted to know what was going on in Belfast, and we wanted to know what was going on in South Africa. It was clear from the outset that he was no fool. No pup could be sold to him. And we appreciated that – because we were certain that the truth alone would exonerate our struggle.

And that was the basis of our relationship. If we could answer his questions, we would. He was at every republican protest and Sinn Féin press conference and covered all the major events throughout 1980 and 1981, particularly the two hunger strikes. The hunger strike period fascinated him, and, in particular, Bobby Sands, whom he once visited.

Later, Tom told me that Beresford was considering writing a book about the hunger strike and that he had been made aware of the ‘comms’ archive.

The Movement agreed to give him access to the comms. He was given the use of a small front bedroom in Iveagh Drive, Belfast, to do the transcriptions. He later wrote:

“There was a bustle at the front door and in walked Danny Morrison from Sinn Féin with shopping bags stuffed full of screwed-up comms. As I began unscrumpling them in an upstairs bedroom I realised I had been given a writer’s goldmine. I had assumed the comms would be little more than military-style reports and commands. But in fact they contained the writers’ most private thoughts, confided to close comrades. Everything seemed to be there, down to a nightmare dreamed by Brendan McFarlane, officer commanding IRA prisoners, the night before, as they waited helplessly for Bobby Sands to die.”

I would call into the house to see what progress he was making and it was apparent that he was greatly moved, was emotionally struggling, and could not comprehend how young men, including two who were married, Bobby and Joe, would die or could die in such a manner over such a prolonged period. At one point I burst into tears and apologised and he stood there, on the landing, silent, his head bowed.

He was in awe of those ten men and he could never come to terms with 1981 – as none of us who were around have, either.

After he had seen them, the comms were then moved to the National Library in Dublin where they are preserved [though have yet to be digitised and made generally available to students, researchers, historians and journalists].

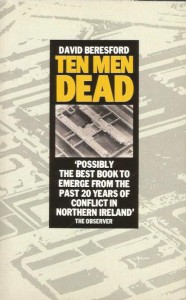

Out of them Beresford produced the classic book about the hunger strike, Ten Men Dead. My future wife, Leslie, was the researcher for the book.

His publisher, Grafton, told him they would print 10,000 copies. He said they would need to print 50,000. Then, he discovered they only printed 5,000. Then they had to keep re-printing it! He tells the story of his writing of the book and its production in an essay he wrote for Hunger Strike – Reflections on the 1981 Hunger Strike, published by Brandon in 2006.

He also wrote of how the book became ‘an underground classic’ and of how proud he was that it had never been out of print in the past thirty years.

David Beresford, who suffered from Parkinson’s disease for two decades, died last week in South Africa.

IN 2006 the Bobby Sands Trust sponsored a book, Hunger Strike – Reflections on the 1981 Hunger Strike, which included almost fifty essays, poems and commentary by a variety of activists and writers, and included Edna O’Brien, Nell McCafferty, Ulick O’Connor, Jude Collins, Ronan Bennett and Christy Moore, Gabriel Rosenstock, Roy Greenslade, Ken Loach, Peter Sheridan and Anne Cadwallader among others. The following is the chapter written by David Beresford at a time when he was struggling with his illness.

Writing Ten Men Dead

– David Beresford, journalist

“There is no need to fasten a bell to a fool,” goes a Danish proverb. And, thinking back to it, I dropped enough clangers to let them know I was coming.

It must have been in 1976 that I had my first taste of Ireland. It was love at first sight. Like falling in love with a gypsy woman, I suppose. I did not begin to understand her, but the passion could not be denied. I was a South African foreign correspondent, working for what was then the biggest newspaper group in the southern hemisphere (before Tony O’Reilly got his claws into it). I’d flown to Dublin, planning to take a train ride north to Belfast the next day.

But the next morning I was told there was a bomb on the railway line and trains to Belfast were cancelled. Not to worry, I was reassured, this often happened and all I had to do was take a bus to Derry then I could catch a train from there to Belfast. So that was what I did, finding Derry railway station looking like bombed-out Berlin at the end of the war. But it seemed that life continued as normal there. And my train to Belfast would be departing in about an hour as scheduled.

Determined to play the foreign correspondent without further ado, I inquired of a gnarled old porter sweeping the platform as to where I could find the nearest working telephone.

“Who do you want to phone?” he asked.

“A taxi,” I said.

“Where do you want to go to?”

I waved my hand in a vague sort of way, “Oh, around.”

He led me to a phone booth and offered to make the call. I thought that most gentlemanly and handed him some coins. After several calls and muttered conversations he turned to me and said, “Sorry. Taxis are all taken.”

“Here. Let me speak to them,” I said, reaching for the phone which he reluctantly surrendered. Adopting a plummy, pommy accent, which white South Africans in those times used to mistake for the voice of authority, I made a short speech declaring the need of the good people of Derry to get their public relations in order if they wanted the world to know the truth of their fair city.

“Hello,” I said, assuming the silence was a tribute to my blarney.

“Wait outside. We’ll pick you up in five minutes,” said a voice.

“They’re coming,” I announced triumphantly to the big-eyed porter, placing the phone back on the cradle with proud aplomb.

As I waited outside I pondered momentarily as to why taxi drivers in this part of the world used the collective pronoun. I didn’t have to wait long.

An unmarked Sedan pulled up.

“Where d’ya want to go?” asked the driver.

“Derry?” I hazarded.

“The Bogside?”

“Is it nearby?” I asked, envisaging a town some distance away and worried about my train.

“Right under the city wall,” he assured me, cheerily.

Driving around the Bogside it quickly became apparent that my driver knew his way, giving a running commentary on who had been shot on that street corner last Thursday, who had been hit by a sniper up there on the wall on Friday and the wee young girl killed just there by a rubber bullet.

Warned by people in Dublin never to ask a man his religion in the North, I asked cunningly, “Do you feel safe around here?”

“Oh, aye. I live here,” he said, waving nonchalantly to a group of men on a sidewalk. They waved back enthusiastically.

The car pulled up.

“See the soldier looking at you?” said the driver. I stared back in horror. It was the first time anyone had pointed a firearm at me! The soldier was obviously trying to identify me with his telescopic sight, but that seemed no excuse for the breach of bushveld lore drummed into me from childhood: “Don’t point guns.”

As we pulled up at the skeletal Derry railway station I asked the driver how much I owed him.

“Nothing,” he chuckled. “This isn’t a taxi, you know.”

“What do you mean?”

“We get a bit worried when a man with an English accent phones up and wants a tour of Derry.” With a wave he accelerated away.

A couple of years later I was back in Ireland, this time as The Guardian’s Belfast correspondent.

“What’s a South African doing in Ulster?” asked the Unionist Euro MP, John Taylor, when I was introduced to him at a Fortnight party.

“Oh, I feel at home here.”

“What do you mean?” he demanded.

“Well, you’ve got partition and we’ve got Bantustans.”

It wasn’t the way to make friends, particularly unionist friends, and to some it might seem over simplistic, but ‘the joy’ of the Irish conflict to me, as a writer, a reporter and a commentator was that it was so simple and the parallels with South Africa so obvious. The Irish border was a gerrymander in just the same way as the ‘historic’ borders of the Bantustans. To me both of them were nothing more than wishful thinking by politicians who had found themselves on the wrong side of history.

I could feel a twinge of sympathy for the unionists, fighting for their lost cause just as I did for the Voortrekkers who had fled British imperialism and, when cornered, fought the British army to a standstill. But that feat of arms no more justified apartheid than Lambeg Drums justified Protestant rule.

Some of the parallels were eye-openers even to me, when I discovered them.

In South Africa, for example, we (the liberal, opposition Press) often used to cite the example of the unarmed British bobby as the epitome of civilised policing. It was startling to realise that their equivalent in Northern Ireland, the RUC, was carrying out roadside executions (shoot-to-kill) comparable in their cynicism, if not in viciousness, to the political murders of the South African security services.

Such perspectives were, of course, anathema in the eyes of most British newspapers. But I was blessed in my employment by The Guardian, a newspaper which was, at times, quite prepared to run an editorial taking one position on Ireland and a piece by me on the opposite page arguing the contrary.

So, I felt I was well-positioned when the major story of my Irish posting broke, with the hunger strikes. Again we had to deal with some wishful thinking on the part of politicians, notably from Mrs Thatcher, such as her claims that the hunger strikers had been ‘ordered’ to die and that there was an IRA plot to burn down the Short Strand in Belfast.

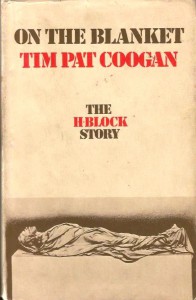

But, ludicrous though such claims might be, there were endless, unanswered questions surrounding the hunger strike by the time it ended. And it was with eagerness that I waited for the emergence of a book answering them, a book that some Irish writer, assuredly, must be busy finishing. Somebody like Tim Pat Coogan, whose On The Blanket, an account of the run-up to the hunger strike had been an Irish best-seller.

But, ludicrous though such claims might be, there were endless, unanswered questions surrounding the hunger strike by the time it ended. And it was with eagerness that I waited for the emergence of a book answering them, a book that some Irish writer, assuredly, must be busy finishing. Somebody like Tim Pat Coogan, whose On The Blanket, an account of the run-up to the hunger strike had been an Irish best-seller.

Eagerness changed to impatience. “Why can’t I do it?” I asked myself as the months passed without sign of such a book. I had never written a book, but one has to start somewhere. Eventually I decided to go for it, making an approach to Sinn Féin, asking for help in getting cooperation from the IRA which I assumed would be my main obstacle.

My pitch was a simple one: unless Thatcher was right and the IRA had ordered the hunger strikers to their death, which was clearly ludicrous, they had nothing to lose and lots to gain from such a book. I said I was prepared to submit the final manuscript to them, for checks on possible inaccuracies, and they could make representations to me as to any objections they had. But the final decisions were mine and they would have no veto.

To my surprise I was promptly given a go-ahead.

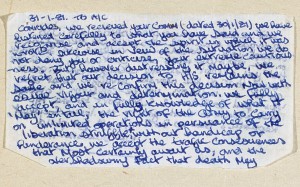

“If you’re going to do a book on the hunger strike you’ll need the comms,” Tom Hartley of Sinn Féin observed one day. I knew what a ‘comm’ was – a message written by prisoners on a cigarette paper and smuggled out on visits – because one or two reports in the local papers had described how the prisoners used them to communicate with the external leadership. But I had not appreciated the extraordinary number of them, or that the IRA had kept them. So I duly sent a message asking for access to the comms.

I remember the day clearly. It was winter and freezing cold, with slushy snow and ice on the pavements. I had been told to wait in a West Belfast safe house. I had an Epson PX8 with me, one of the early laptop computers, with a screen of about 12 lines and a built-in mini-cassette recorder as a primitive hard drive.

There was a bustle at the front door and in walked Danny Morrison from Sinn Féin with shopping bags stuffed full of screwed-up comms. As I began unscrumpling them in an upstairs bedroom I realised I had been given a writer’s goldmine. I had assumed the comms would be little more than military-style reports and commands. But in fact they contained the writers’ most private thoughts, confided to close comrades. Everything seemed to be there, down to a nightmare dreamed by Brendan McFarlane, officer commanding IRA prisoners, the night before, as they waited helplessly for Bobby Sands to die.

I had been warned that I could only have a limited time with the material. I was then a fast touch typist and my half-frozen fingers started flying over the little PX8 keyboard as I tried frantically to get it all down, verbatim.

As I read them, I realised there were a couple of holes. I had been told, quite frankly, that some comms would probably be kept from me, as being “just too sensitive”. By placing what I did have in chronological order I quickly found out where the sensitive areas lay: the collapse of the first hunger strike at the end of 1980, and the initiative of the (Catholic) Irish Commission for Justice and Peace during the second.

By the time the book was published I had the details of the missing areas, showing Mrs Thatcher had lied when she had made her often-repeated statement that her government “does not talk to terrorists”.

My publisher was Grafton (a subsidiary of Harper Collins) which is now defunct. I had received only a nominal advance and now, inspired by my good fortune, I decided I needed some more money to cover costs. The Guardian had asked me to open a bureau in Johannesburg. South Africa was beginning to burn and the posting was one I could not turn down. The editor, Peter Preston, had given me two months’ paid leave to finish the book. Now I just needed a couple of hundred pounds so I could buy a second-hand jalopy to rush around Northern Ireland in search of the interviews I would need.

Highly excited at my good fortune with the comms I could hardly wait to boast of it to my young editor at Grafton. I phoned and made an appointment, little realising that my biggest problem with the book would be more with Grafton – the very people who would share my good fortune – than with The Guardian or, for that matter, the IRA.

My young editor did not turn up for the meeting. Instead there were two senior editors, looking grave. After the introductions I excitedly told them what I had got, showing them some of the transcripts. They just looked at me po-faced. I could not understand their lack of enthusiasm. After all, this was the ‘age of terrorism’. The IRA was the oldest and most sophisticated ‘terrorist organisation’ in the world. The book was not only the story of what was probably the most serious crisis in that organisation’s history, but the comms, which stood no comparison in the annals of prison literature, gave an unprecedented insight into their thinking during that crisis. And here were these men looking at me po-faced!

The enthusiasm was lacking, but at least the money was not. I bought an old Peugeot and wrote the book, beginning it in London and finishing it in South Africa.

I was having a celebratory glass of champagne with my cousin, Robert Nugent, in the garden of his Johannesburg home when the courier arrived to take the completed manuscript. Bob was a barrister (he is now a judge of appeal) and he had earlier cast a professional eye over my contract with Grafton, suggesting I include a clause by which if the book was ever put of print for more than three months the copyright would revert to me.

Newspapers are, of course, part of the publishing industry. As a journalist and something of a long-time book-worm I had strong opinions as to how a book should be marketed, at least in its packaging, and had conveyed those opinions to both my London agent and to Grafton. Most of it was self-evident. The biggest marketing problem we faced was that the Irish hunger strike had been given saturation coverage by the media at the time. The public was sure to be tired of the subject – even though publication of the book was coming five years after the event.

There should be nothing on the front and back covers to evoke press coverage of the hunger strike, I begged them. No text describing it as the story of the 1981 hunger strike. No clichéd press photographs as the cover design, no aerial shot of the prison, no picture of alienated youths tossing petrol bombs at army or police forts.

I spent hours crafting a short blurb for the back cover, stressing the unique nature of the comms. And Ten Men Dead, which I feared was reminiscent of the childhood rhyme, was a working title only, I stressed. I would come up with a better one.

I spent hours crafting a short blurb for the back cover, stressing the unique nature of the comms. And Ten Men Dead, which I feared was reminiscent of the childhood rhyme, was a working title only, I stressed. I would come up with a better one.

No prizes for guessing what the published book looked like. “It’s too late,” came the answer when I offered a new title. Dead Faces Laugh was my choice, the last line from a Yeats’ play about a hunger strike.

The front cover was an aerial shot of the H-blocks. Slashed across it were ’the story of the 1981 hunger strike’. The blurb on the back might have been designed to persuade would-be buyers that they had read it all before.

Shortly before publication I had been told the print run would be 10,000. I had protested strongly that the book would sell at least five times that.

“It’s a question of warehouse space,” said Grafton, reassuring me that a new run could be printed in a matter of days.

The Guardian, as ever, did me proud, taking out a full-page advert in The Observer to launch the book and running a four-part serialisation, kicking off with the disclosure that Mrs Thatcher’s government had engaged in negotiations with the IRA during both the 1980 and the 1981 hunger strikes.

The book leapt into the London and Irish best-seller lists and was sold out in three days. Grafton, it transpired, had printed only 5,000. It took several months for them to do a re-print. Subsequently I was invited to a Grafton board-room lunch so the publishing house could ‘apologise’ to me. During the lunch I challenged the managing director. I could forgive the title and everything else on the front cover, but I just could not understand why they had ignored my carefully wrought blurb for the back, in favour of the boring, platitudinous rubbish they had used.

“Ah yes, the blurb,” he said. “It was written by a committee.” He refused to say anymore on the subject.

He did, however, make another remark which I was to recall years later.

”There are some books,” he said, “which become underground classics and do unexpectedly well, continuing to sell for years after publication. This book could turn out to be one of them.” He had got at least one thing right. Twenty five years after the hunger strike Ten Men Dead is still in print and selling strongly.

But my frustration in the early years of the book’s life was intense, in the face of what I saw as the complete failure by Grafton to market the book. A hundred copies did make it to South Africa, but the marketing manager of the local distributors locked them away in his safe on the grounds it was about the IRA and therefore ‘subversive’.

Although I was by now based in South Africa I used to spend as much of my spare time as I could in London, where my girlfriend, Ellen, and our baby son, Joris, lived in Fulham. Just around the corner there was a local branch of WH Smith. The manager of the shop had tired of my persistent complaint that they did not stock Ten Men Dead and one day he announced he was bringing in three copies, “just to see how it sells.”

Every morning I would pop around to buy The Guardian and to check how the sales of my book were doing. The sales attendants insisted on placing them in the ‘history’ section, on the bottom section. So I would re-place them on the ‘best-selling’ shelf at eye level, usually on top of the latest Jilly Cooper block-buster, featuring a woman’s backside, erotically clad in the tightest possible jodhpurs.

Two of the copies of Ten Men Dead had sold and they were down to one when I walked into the shop one morning and did my usual job of re-arranging before standing in the queue, clutching my copy of the morning newspaper. Suddenly, to my astonishment, I heard two hefty and dusty Irish navvies in vests, obviously from some nearby building site, ask the manager for a copy of Ten Men Dead.

“You’re in luck, we’ve got just one copy left,” said the manager, reaching down to the history section.

“Stuuuuh… I’m sorry, it looks like we’re sold out.”

“No, no,” I cried. “There it is, there it is,” pointing to where the book stood proudly on the best-seller section.

“That’s it!” said one of them, grabbing it. As they paid and headed for the exit my pride of authorship became too much for me.

“Do you like that book?” I asked. They looked at me as if I was bats.

“You know, I wrote it,” I said with a big smile. The two of them hurried out the door throwing anxious looks over their shoulders as they went.

Watching through WH Smith’s plate-glass window as they walked up the street, I thought: “Hell, it was worth it.”

I hesitate in my writing, recognising the ambiguity. Was what worth it?

I met Bobby Sands. He was the only one of the hunger strikers I did meet. I went in on a visit on the third day of his fast. Being a journalist and having an eye on an ‘intro’ my first question was: “Do you think you will die on this fast?” I had been asked to take in some cigarettes for him and he was lighting one. He paused, said “Yes, I think I will,” and took a pull on his cigarette. I’m not sure who started it, but we both chuckled at the incongruity of the answer as the cigarette smoke spiralled upwards.

I did see him again, but then he was dead in his coffin at the house in Twinbrook Estate. As I looked at his waxen face I was struck again by the incongruity.

I love Ireland, my memories of it, but I am not an Irishman, an Irish nationalist, or an Irish republican. I guess I just don’t hold to man-made borders and divisions whether they are in Ireland, or South Africa. So I cannot assess whether it was “worth it” in terms of the “five demands”, or even constitutional change. Instead I am driven to use the words of W.B. Yeats with which I concluded ‘Ten Men Dead’:

When I and these are dead

We should be carried to some windy hill

To lie there with uncovered face a while

That mankind and that leper there may know

Dead Faces Laugh. King ! King ! Dead faces laugh.