My mother died two weeks ago and was buried in Milltown Cemetery in the grave of my father, who predeceased her by ten years. She suffered a massive heart attack. I was actually chairing the AGM of Féile an Phobail when Alice, one of the carers at Grovetree Residential Home, waved to me from the wing of the theatre in Cultúrlann and called me out. We drove to Grovetree where the emergency team were working on mom and I accompanied her in the back of the ambulance to the A & E at the RVH. She was moved to the cardiac unit in Ward 5C and died there on Saturday 16th April.

My mother died two weeks ago and was buried in Milltown Cemetery in the grave of my father, who predeceased her by ten years. She suffered a massive heart attack. I was actually chairing the AGM of Féile an Phobail when Alice, one of the carers at Grovetree Residential Home, waved to me from the wing of the theatre in Cultúrlann and called me out. We drove to Grovetree where the emergency team were working on mom and I accompanied her in the back of the ambulance to the A & E at the RVH. She was moved to the cardiac unit in Ward 5C and died there on Saturday 16th April.

We were all crying and holding and comforting each other.

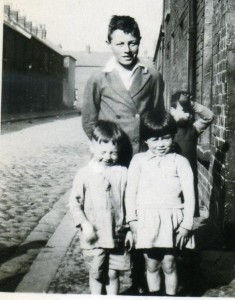

At 87 she had outlived her nine brothers and sisters, but her life as a fully sentient person was cut short at the age of 57, the week that the hunger strike ended. The photograph here was taken in Ward Street around 1928. It shows my Uncle George towering over Willie in the background, and, in front of him, Seamus and my mother Susan.

A few years ago, in my book All The Dead Voices, partly a family history, I wrote a chapter about my mother and called it ‘Down to Grovetree’. Here it is…

It was in the back of a taxi that I last remember having a proper conversation with my mother. She had been complaining of headaches of late and her doctor said her blood pressure was high. It was around October 1981, when the H-Block hunger strike had ended or was ending, and we were coming from the funeral of an old friend of my father’s, Jimmy McGivern, whose son was once engaged to my sister Geraldine, and in whose butcher’s shop I had worked when I was fifteen and in love with Marian.

I was married and living not far from my parents so we all got out of the taxi together and said our good byes. A few days later, I was being interviewed by a television crew outside the Sinn Fein offices on the Falls Road when a car pulled up and a friend, Sheila McVeigh, quickly alighted. She told me that my mother had just been rushed to the hospital with a suspected heart attack. The British army had been raiding the republican houses in the street and were heading into ours when my mother collapsed at the front door. I cut short the interview and Sheila and I went to the Royal Victoria Hospital only to find out that it wasn’t their ‘take-in’ day and that my mother had been admitted to the City Hospital. We went to the City and into the casualty. I saw my mother lying on a bed, waiting to be attended. I spoke to her but she was completely disoriented and her face was crimson. She was then taken into the theatre.

I was quite nervous being there and feared assassination because the City Hospital was close to the loyalist Sandy Row and that year I had been prominent on television during the hunger strike and the by-elections in Fermanagh and South Tyrone. My father came immediately from work and I left to go home and mind my younger brother.

As it turned out my mother had suffered a brain haemorrhage. She was transferred to the Royal Victoria Hospital on the Falls Road, which specialises in neurosurgery, and went through a critical operation. She never recovered and she lost her ability to memorise. It was a massive blow to our family but at least she was still alive. She had to be cared for full-time whilst my father continued to work nights in Telephone House, where he was a deputy supervisor. Although various friends, neighbours and relatives helped out, a lot of the responsibility after his school hours fell unfairly on my young brother Ciaran who was just thirteen, and represented a reversal of the conventional mother and child relationship.

My mother had no will, had to be told to do things and didn’t initiate any conversation. She liked to sleep a lot and in fact if you turned your head she would be asleep in an instant. The fact that she would never recover sank in slowly. On one occasion, when my sister Margaret was visiting from England my mother, a heavy woman, slipped and fell in the bathroom and Margaret couldn’t lift her. She phoned me. I came immediately to the house and helped her up. But we discovered that she had hurt her ankle and took her to the hospital where she was admitted for a fracture. Miraculously, as a result of the accident, she came alive and was animated that night. When I visited her she gabbled away about the nursing staff, invented incredible adventures and love affairs between them and whispered that the man opposite, visiting his wife, was in the Special Branch.

I was overjoyed. Even though she was talking gibberish, she was talking. It was as if some wire in her brain that had been severed during her original fall had been reconnected as a result of her accident, and that gave us hope. I phoned my younger sister, Susan, and told her to get down to the hospital as soon as possible to see the change. But by the time she arrived my mammy had reverted to her silent state. The medical staff explained that the anaesthetic probably through some side effect had triggered my mother’s activity.

Over the years she had put on weight, became ponderous and fell a lot. She couldn’t properly negotiate the stairs, required a lot of laundry, and sometimes, half-dressed, she escaped in the early hours and would make her way to her old house in Andersonstown, looking for her mother who died in 1959. My father resisted putting her into a residential home as long as possible but it was the best decision in the circumstances, where she would receive professional care, though that never stopped us feeling guilty.

She is visited regularly. When you go in to the TV lounge she is usually sitting with her chin tucked into her chest, sleeping soundly. She doesn’t know that her youngest daughter Susan, who had been in need of a heart, lung and liver transplant, died in the autumn of 2001, that my two older sisters and I have all been divorced and two of us remarried, that Ciaran’s been to jail, I’ve been to jail, my Daddy’s moved house, that her sisters May, Anna and Eileen have died, that her brothers Harry and Willie are dead, or that she has great grandchildren. Nor that her friend in the residential home, Noreen Johnston, has been dead three years. If you ask her where Noreen is she will say, ‘She’s around somewhere.’ She doesn’t know what day it is, does no harm, hurts not a fly, and is in a state of grace, so that when you visit her you feel not just the old affections but that you are in the presence of innocence incarnate.

You can get her to tell a white lie to reveal how protective she still is of others. If you ask her was anyone down seeing her last night she will say, No, because she cannot remember. But if you appear annoyed and rejoin with an invention, such as, ‘Well, I’d love to know why Eileen McKee told me she was down’, she will say, ‘Oh yes, what am I talking about, Eileen was here.’

I once did a very stupid thing, thinking that she would understand I was only fooling. I said to her, ‘What do you think of my Da! He was out gallivanting last night again and left the dance with a big blonde on the end of his arm.’ The blood drained from her face and she started to cry like a jilted young girl as I reassured her I was only joking.

I don’t believe she did any wrong in her life or broke any hearts. I asked her recently who was the first boy she ever went out with. She thought for a moment: ‘Willie McDermott.’ Where from? ‘Distillery Street,’ she replied in an instant. I asked her what age she had been and she said sixteen. My mother at sixteen: a whole universe before her.

Whatever happened to Willie McDermott?

‘I don’t know,’ she said and sank back into silence.

Everywhere she went, she was the life and soul of the party, says my Aunty Kathleen, her sister and four years her junior. Kathleen remembers her in the Club Astor in downtown Belfast getting up for a dare and – sober! – doing a Russian dance on top of a table. They went to the Plaza Ballroom where they got in free because the band leader was their brother, Jack White. They thought themselves ‘big girls’ because they smoked, though I never saw my mother smoke properly. She seemed to summarily kiss and suck rather than deeply inhale the cigarette, then would blow out the smoke as if she was blowing out a candle.

Her best friend was ‘Girlie’ Brown. During the war Girlie’s brother was in jail for IRA activities yet Girlie joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (part of the Territorial Army). All the girls used to go roller-skating on the Shankill Road, even though Girlie couldn’t skate. Kathleen introduced Girlie to an American soldier, GI Frank Falsetto, who couldn’t skate either, so the couple sat all night talking. When Girlie married Frank and went off to the USA I am sure it left a gap in my mother’s life. But she was soon married herself and within eight years had four children. When we were kids she talked about Girlie constantly and they wrote to each other for three decades.

I used to dash home from primary school and the first thing I did was put on the radiogramme and change the station from the Home Service to the Light Programme. On this particular day a Bridie Gallagher song, ‘A Mother’s Love’s a Blessing’, was on the radio. My mammy came in from the kitchen and stood, then began sobbing at the chorus, ‘You’ll never miss your mother’s love, ’Till she’s buried beneath the clay.’ I asked her what was wrong and she said she missed my granny. I caught her secretly crying quite often for about a year after my Granny White’s death.

When I recall the parties in our house in Corby Way I remember most her singing ‘Eileen O’Grady’, part of which goes:

Come, come, beautiful Eileen,

Out for a drive with me.

Over the mountain and down by the fountain

Over the high road and down by the low road.

Make up your mind,

Don’t be unkind, and we’ll drive to Castlebar.

To the road I’m no stranger

For you there’s no danger,

So hop like a bird

On the old jaunty car.

In her seventy-seventh year, after suffering for some time from pyorrhoea, and with many of her teeth reduced to black stumps, she had all her teeth removed. I was visiting her and we were alone in the lounge of the home. I asked her did she remember the words of ‘Eileen O’Grady’ and her eyes lit up. I coaxed her to sing me a verse and she sang but the words came out gummy and I suddenly realised how old my mother was and I was very sad because the course her life suddenly took twenty years ago, because I remember her singing and laughing and I remember the young woman who brought me to school on my first day and how I looked back and loved her.

Along with my father, she comes to us on Christmas day for dinner and will eat the goose and stuffing and sprouts and the Christmas pudding but will not gossip nor ask for any more gravy or ice-cream. She has no volition and you are not even sure if putting a party hat on her head and asking her to pull a cracker is fair to her dignity even though, as I said, she herself was once the life and soul of the party, a singer, a dancer, a joker, who now remembers little of twenty minutes ago, never mind twenty years ago.

My mammy never wanted us to leave home, to leave the nest. My late sister Susan was exactly the same a few years ago when her daughter, Cathy, left home for college in Dublin, and later to a flat in Belfast. The last time our family was all together for Christmas dinner, before my sisters Margaret and Geraldine went off to England to get married, was thirty years ago. I was seventeen and Ciaran, the baby, was just two.

Although my father worked six days a week and brought in the money, it was mammy who turned that money into the loving cornucopia that was our simple home, the biscuits in the cupboard, the lemonade in the fridge, the clean clothes that appeared in the wardrobe from nowhere, the made beds.

Santa Claus was now coming for Ciaran alone, but the rest of us also got what we wanted and had been hinting at for weeks in advance. If I close my eyes I can still see her in her apron out in the steaming kitchen, testing the turkey, turning over the roasties, checking the stuffing, baking her own pudding, lifting the lid of a pot, tasting the soup, her singing a little song which I think she invented, sometimes biting a nail, uncomplaining, triumphant, and content to be giving herself to us, as if she couldn’t give us enough, while we sprawled on the chairs and sofa and fought over the television and give each other orders.

We all sit at the table like royalty while she serves us and we forget to tell her how good her dinner is and discover only later, and too late, that no one has ever made soup like hers, and that from out of her tiny kitchen she produced a banquet.

In 1916 loyalists drove my Granda and Granny White and their five children out of Blackwater Street. They moved into a Catholic street close by, Ward Street, where my mother was born Susan White in 1924. When she was six they moved to Distillery Street but they were put out of there in the mid-Thirties, again by loyalists, and moved to Andersonstown Park, which was then on the city limits. Those first two streets she grew up in were knocked down and redeveloped in the 1970s but from the bench in the grounds of her residential home she looks on to Distillery Street but doesn’t know that this is where she grew up.

Distillery Street, Blackwater Street and Ward Street, were offshoots of one of the main arteries through West Belfast, the Grosvenor Road. Her nursing home is at the junction of the Grosvenor Road and Cullingtree Road and takes its amalgamated name after them, Grovetree House. And that is why, when we are going to visit her, to sit beside her and hold her hand, to talk to her and try to draw out her memories and revisit the past, we just say we’re going, ‘Down to Grovetree.’