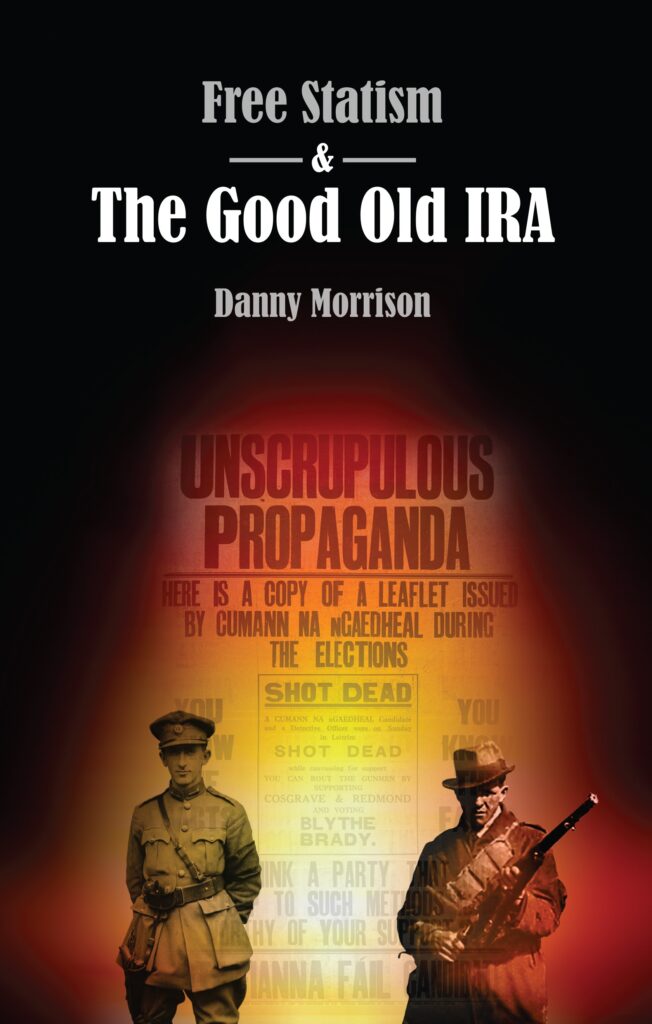

Ciarán Quinn, Sinn Féin’s Representative for North America, writing in a personal capacity, reviews Free Statism & The Good Old IRA. (Details of where the book can be bought are at the bottom of this page.)

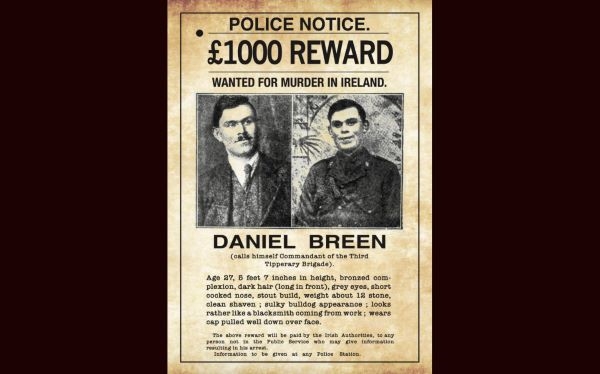

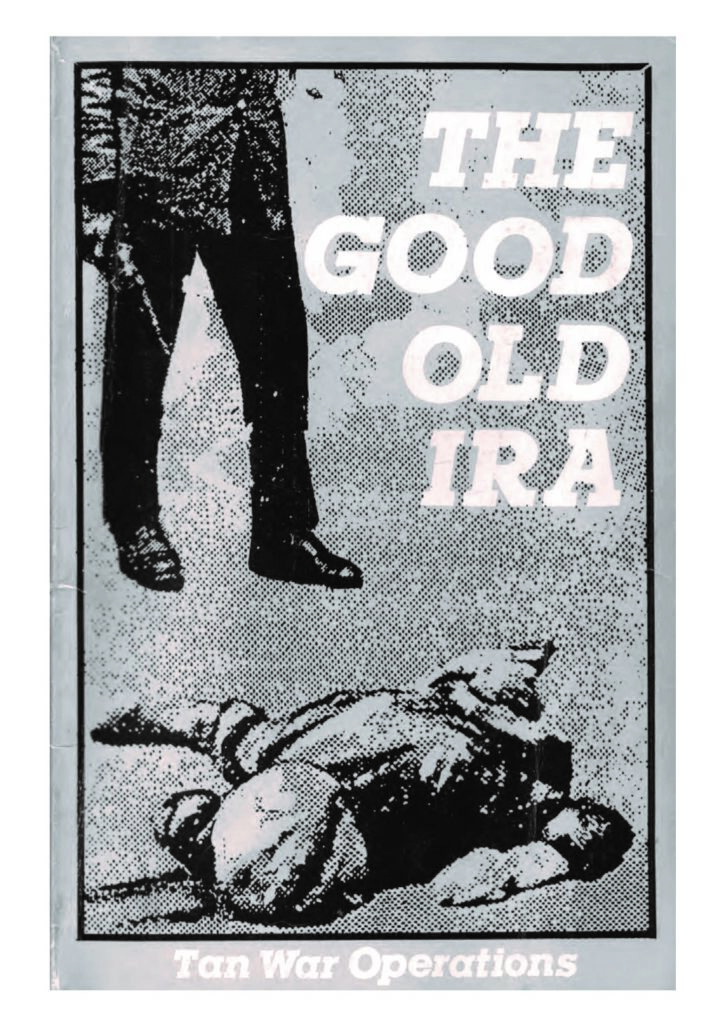

THE GOOD OLD IRA was a pamphlet published in 1985 by Sinn Féin. At the time Danny Morrison was the Director of Publicity for the party. It detailed the brutal reality of the Tan War. It was a challenge to the hypocrisy of those who celebrated the Old IRA of the 1920s while attacking the IRA in the 1980s.

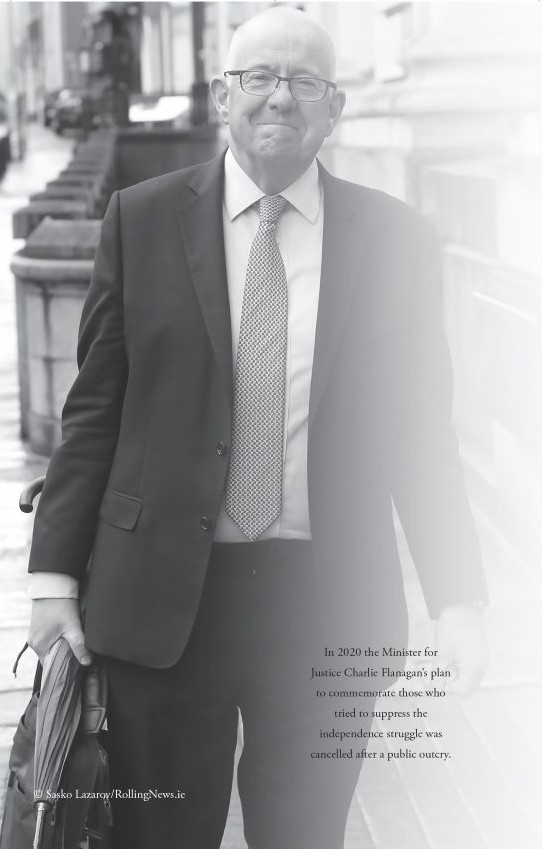

The publication was a response to the call of the then Fine Gael Minster of Justice, Michael Noonan, for people to follow the lead of Michael Collins.

Collins had directed the campaign of guerrilla warfare, authorized close-quarter assassinations and fundraising robberies for the IRA.

The original edition was a book of its time. A time of conflict. Out of print since the early 1990s, its status grew in republican circles. Much talked about; but seldom read.

I first got my hands on a copy in 2005 in a second-hand book table at a primary school fundraiser in Cabra, Dublin. I remember asking the price and it was a Euro per book or ‘three for a fiver’. I didn’t know whether to be impressed by the business acumen of the kid running the stall or appalled by his maths. I bought two books, now long forgotten, and a copy of, The Good Old IRA.

It was a simple, compelling piece of propaganda. Contemporaneous newspaper clippings from the Tan War listing the shooting of informers, the killing of civilians, the assassination at close quarters of locally-recruited policemen, and ruthless attacks on the British Army. Besides an Introduction, the clippings speak for themselves. The myth of a ‘Good Old IRA and a ‘Bad Modern IRA’ lay exposed on every page.

I was intrigued when Danny spoke about republishing the pamphlet. After all, things had moved on. The war was over and the IRA had left the stage. We have a peaceful and democratic pathway to Irish unity. A generation on from the Good Friday Agreement. Was it still relevant?

The answer is to be found in the first half of the book. The book is in two parts. The first is an extended essay on the birth, rise and cultural shaping of Free Statism. The second part is a reproduction of the 1985 pamphlet but with additional sections on the English campaign, Disappearances, and the Catholic Church.

This new edition is very much a book of this time.

The partition of Ireland and subsequent civil war created a paradox for successive Irish Governments that has not been resolved. The Peace Process put further pressure on myths and orthodoxies that have sustained the state since its inception. How do you honour a state established by a Treaty that partitioned a nation under the threat of immediate war at the hands of the then British Government?

Following partition Irish territory consisting of Twenty-Six Counties gained a degree of independence from Britain and became known as Saorstát Éireann (Irish Free State); the unionist-dominated, northeast Six Counties was carved out to create the state of ‘Northern Ireland’.

In the north since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, a generation has grown up in relative peace and looking to the future in a progressive Ireland within the EU. The absolute unionist majority is gone. Brexit has demonstrated that the union with Britain is not in the interests of the people of the north. The Good Friday Agreement, endorsed by the people in referendums, is not a constitutional settlement but a framework for managing political differences today and tomorrow. Partition is not permanent. A democratic and peaceful pathway is open to Irish unity.

In the Twenty-Six Counties, home rule did become Rome rule, so to speak. After decades of conservative governments, a new progressive Ireland is being shaped by the people in the South who have spoken loud in popular referendums for marriage equality and abortion rights. The pillars of the state since partition have been challenged; the church, the establishment parties, the media consensus, and the power of the insiders.

For some, the Twenty-Six Counties is Ireland. The North is a place apart. Partition led to a partitionist mindset in politics and culture. As one unsympathetic person disparagingly remarked to me, ‘the people in the North think they are more Irish than the Irish.’

Danny Morrison sets out to explain how we have got to the point where an Irish Government refuses to plan for Irish unity. A time when television maps of Ireland create a coastline between Louth and Donegal.

Divided into chapters the book lays out the development of modern Free Statism from pre-1916 to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

The historical chronology of the book is extremely well researched with references, quotes, and extensive footnotes. The nerd in me does like a good footnote! Along the way, in these chapters, Danny highlights the experience of Northern nationalists who were all too absent from the Southern narrative and challenges the prevailing consensus.

One of the myths was that the ‘Old IRA’ had a mandate following the 1918 election. This was a landslide election for Sinn Féin and led to the establishment of the First Dáil. As the author points out, planning for the coming conflict was well advanced with the recruitment and drilling of volunteers and the importation of weapons, meaning that the election was not a plebiscite on war. The IRA was taking action regardless: just as it had in 1916.

The strongest writing in these chapters not surprisingly relates to the North. It is essential reading for those who want an informative and accessible account of the Northern nationalist experience.

The most intriguing section is the chapter on Modern Free Statism. It tracks the arc of the ideological development of Free Statism. In 1921 the signing of the Treaty was never portrayed as a victory but an alternative to a bloody and brutal war. It was never to be an endpoint but a staging post.

Michael Collins, the hero of then non-existent Fine Gael described it as ‘Freedom to achieve freedom’.

It was Britain’s demand on the Free State that it suppress republicans in their garrison in the Four Courts which precipitated the Civil War. The atrocities of the Civil War were carried out in the name of defending the Free State. The later executions of republicans by the Fianna Fáil government of Éamon de Valera, was, again, described as defending the State. Today, some seek to celebrate the Treaty and partition. A position that was never adopted by the signatories of the treaty at the time.

All of these actions required an ideological underpinning: Free Statism, the promulgation of the illusion that the southern state is ‘Ireland’. The endpoint.

The North, however. That’s separate. That’s different. That’s other.

Free Statism rationalized partition and turned a blind eye to the repression in the North. It has proved impossible for them to square the circle – celebrating those who fought for independence while attacking those who fought for independence. As the book reminds us this reached its nadir when the official video of the centenary to remember the patriots of 1916 didn’t even mention the patriots of 1916.

This is not a book that glorifies violence. It is explicit in its accounts of the brutal reality of conflict. The author makes clear that violence is, ‘the choice of last resort. Not everyone will resist.’

In the introduction Danny Morrison writes: ‘Throughout history during wartime, acts of heroism are accompanied also by cowardice and cruelty. Another universal fact is that civilians, by in large, bear the brunt of the suffering. In conflicts, good people kill other good people . . .’

He quotes Vietnamese poet Nguyen Duy that, ‘In every war, whoever won, the people always lost.’

The relevance of this book today is not just in its historical narrative or its exposing of hypocritical standards. It is at its essence about the future. We are at a tipping point.

Free Statism, as the book demonstrates, historically claimed to defend the state. Post-Good Friday, Free Statism is about defending the status quo and ensuring that those in power stay in power.

We now have the opportunity to realise the vision of generations of republicans – to unite the people and the island. But peace and the achievement of unity is proving a fundamental challenge to the ‘Free State’.

As the book makes clear, peace and unity are an existential challenge to those who managed the state since partition. Free statism is the last pillar of the state left standing.

There is much more to be written and analyzed. The author poses some simple but unanswered questions. Why did the parties in the South not organize in the North? Both Michael Collins and de Valera did stand in elections in the North at various times before the Treaty. In 1922 the adherents of Saorstát Éireann sold the British-imposed partition of Ireland as ‘a stepping stone to freedom’, but in the subsequent one hundred years where was the next stone? It never materialised.

Other questions arise. How do we remember those who fought yet avoid the glorification of conflict? How does the state reconcile itself to the actions of the Civil War and the execution of republican prisoners with the continuation of partition?

A further book could be written on the political articulation of Free Statism and Irish unity.

In the 1950s Sean Lemass developed a policy on the rationale that unionism was the majority in the North therefore unity could only be achieved with the consent of unionists: a policy blind to the experiences of second-class northern nationalists and which condemned them to sectarian rule. That has now been replaced by the democratic promise of the Good Friday Agreement. A majority is a majority– though some have attempted to resile from that fundamental democratic truth and argue for a more onerous percentage in favour of reunification and so that a minority can ensure continued partition.

This is a timely and significant book. It is the start of a discussion, not a conclusion. This updated edition with a new and comprehension introductory essay is a must-read and primer for further debate.

The 1984 edition was a book of its time.

The 2022 edition is even more a book of its time.

In Belfast the book can be bought on the Falls Road or online at An Fhuiseog Also available at An Ceathrú Póilíin, Culturlann, Falls Road. In Dublin the book can be bought at the SF Shop, 58 Parnell Square or puchased online. Also available through Blackstaff Press