Brian Rowan did a short interview with me across the phone for a story published in yesterday’s Belfast Telegraph. It is a good analytical piece on “Why we have to forgive before we start to forget.” Here it is in full:

Saville represents a milestone in dealing with the past. But big, set-piece inquiries can never tell the whole story. A wider amnesty may be needed to lay the ghosts to rest, argues Brian Rowan.

It is but one date on a long calendar of ‘bloody’ days – just one day in a decades-long conflict. Whatever questions are answered about the events of January 30, 1972, there will be much about that day – and many other days – that will remain unanswered.

The story of this conflict cannot be understood by examining one page in the book.

“While Bloody Sunday was undoubtedly a significant incident in the conflict, the publication of the (Saville) report highlights the concerns of some that selective incidents are being dealt with while others aren’t examined,” says Kate Turner, director of the Healing Through Remembering project.

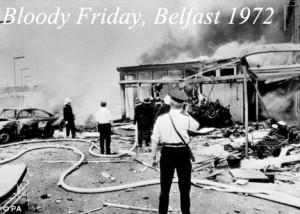

Bloody Sunday stands out because of the scale of the killing. So, too, does Bloody Friday and the IRA bombs and killing on that day – July 21, 1972.

Other days are forgotten – not examined, rarely mentioned – because only one person died, or someone was injured.

There is not yet a joined up approach to dealing with the past – no detailed examination of all the pages in the book that stretches from the beginning to the end of the long wars.

“There is currently a tapestry of different approaches to dealing with the past,” says Kate Turner. “The Bloody Sunday Report is just one of them.

“These include official approaches like the work of the Historic Enquiries Team, Police Ombudsman and the inquiries recommended by Judge Cory.

“But there are also ‘unofficial’ examinations of the past: autobiographies, television documentaries and it seems every day there is newspaper coverage relating to the past, for example on anniversaries.

“What all of these – particularly Bloody Sunday – show us is that issues not dealt with properly don’t just go away.”

But there are those who want the past to go away, who are afraid of its ugly truths emerging.

Faces and minds are set against any process that might dig in the ‘wrong’ places, hidden corners of the IRA and the loyalist organisations and the secret corridors of state and security.

There is much that has been buried, never to be found. The Consultative Group on the Past – headed by Lord Eames and Denis Bradley – was tasked with shaping a process that might bring all sides to some table. But that piece of furniture has not yet been made – and may never be designed.

There is no consensus in terms of what happened and how it should now be addressed. The Eames-Bradley proposed Legacy Commission, with investigation and information recovery units, is buried under the dust on some political shelf inside the NIO.

Danny Morrison was Sinn Fein director of publicity and for years part of the IRA organisation. On the question of the past, he told this newspaper: “You’ll get as many opinions about it as there are people. Some people just want to know the truth and others want justice or revenge.

“Other parties will want self-justification . . . In my opinion the protagonists who bear both political and moral responsibility for either causing the conflict or participating in it will want to shift the blame onto others. So, I remain to be convinced there will be a meeting-point.”

He is not suggesting, or arguing, for a do-nothing approach, rather thinking out loud about how you begin to address the many competing needs and interests.

It suits a government to argue there is no consensus and, therefore, no point in proceeding. But that isn’t going to wash.

“The events of the conflict are now the stuff of history lessons in our schools, despite the fact that we all retain very different versions of what that history actually was,” says Kate Turner.

“So the question is not about whether or not the past relating to the conflict is examined, rather it is: ‘Can this be done in a way that is joined up and just?’

The past is not just about the big players – political, security, republican and loyalist – it is not just about what they want to tell and not tell.

It is about the families of the many hundreds of people who were killed and the many thousands injured and traumatised.

Sandra Peake, chief executive of the WAVE Trauma Centre, says the cost of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry should not be used as a reason for rejecting other processes on the past.

“There needs to be an agreed mechanism for dealing with the past that delivers a victim/ survivor centred approach for all – independent and structured to get the necessary buy-in from those that can provide the answers,” she said. “Truth and justice may often need to be looked at separately. In getting the truth some have given up any hope or right to justice.”

The big, set-piece inquiries, will never tell the whole story. And it might well be that after prisoner releases, and the decommissioning and disappeared legislation, that some wider amnesty across the board is needed.

For many that will be an ugly thought. But it might be the only way to some more explanation and better understanding of what went on here and elsewhere.

Doing nothing, looking away, is not an option – not for this Government, or any other

government.

Brian Rowan will be taking part in this summer’s Féile an Phobail. Here is a description of the event:

Peace Lines and Lyrics, Falls Road Library, Tuesday 3rd August, 12.30pm

At the unveiling of an archive presentation journalist Barney Rowan will be joined by Sinn Fein Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness and loyalist William ‘Plum’ Smith, who chaired the 1994 Combined Loyalist Military Command ceasefire news conference. The conversation will focus on interviews from the early 1990s when Martin McGuinness said the British Government needed to speak to republicans (which, of course, they actually were at this time, privately, though John Major said it would ‘turn his stomach’). Former Red Hand Commando prisoner ‘Plum’ Smith will be asked about the build-up to the CLMC ceasefire – about loyalist fears and concerns after the IRA declared its complete cessation of military operations. Special guest – singer/songwriter Gerry Creen, who has been billed with Nanci Griffith, Brian Kennedy, Juliet Turner and Mick Hanly, and whose signature tune ‘A Rose By Any Other Name’ has been described by Rev Harold Good as “a timely reminder of where we have been, where we are now, and to where we must not return”.