Read several books while I was away in Cuba. Also got to visit the grave in Havana of one of the authors, Alejo Carpentier, whose book The Kingdom of This World was published in 1957. Carpentier died in 1980.

It tells the story of the black uprising against French colonial rule in Haiti in 1803 as seen through the eyes of an old slave Ti Noël. His life and that of the masses is as bad after the rebellion as before when a former slave declares himself King Henri-Christophe and his regime is as corrupt and brutal as that of the former imperialist power.

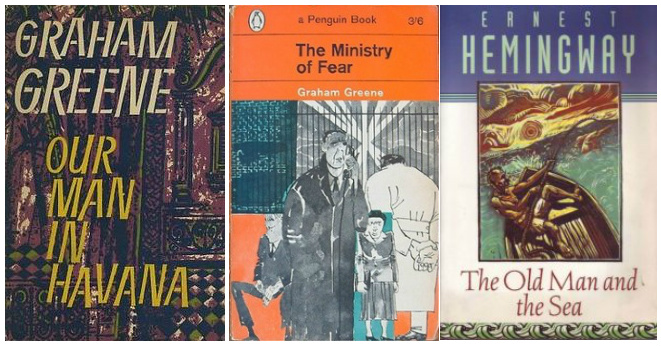

Read again, for the third or fourth time, Our Man In Havana by Graham Greene and had forgotten how funny he could be. Also read Greene’s The Ministry of Fear which I first read in 1970 or 1971. It is set in London during WWII. Had forgotten most of it except the opening pages where a widower wrongly wins a cake at a fête (which contains a microfilm of secret plans – and was supposed to have been won by a German spy). Typical Greeneland fare. It too was very funny in parts, especially when the private detective, whom the main character Arthur Rowe hires, explains the vicissitudes of his work.

“War plays hell with a business like this.” He explained. “The reconciliations — you wouldn’t believe human nature could be so contrary. And then, of course, the registrations have made it very difficult. People daren’t go to hotels as they used to. And you can’t prove anything from motor-cars.”

“It must be difficult for you.”

“It’s a case of holding out,” Mr Rennit said, “keeping our backs to the wall until peace comes. Then there’ll be such a crop of divorces, breaches of promise. . .” He contemplated the situation with uncertain optimism over the bottle. “You’ll excuse a tea-cup?” He said, “When peace comes an old-established business like this — with connections — will be a gold-mine.” He added gloomily, “Or so I tell myself.”

Like Our Man in Havana the love angle in The Ministry of Fear is an unconvincing, lazy contrivance which Greene should have either forgotten about completely or worked on harder.

Also revisited Hemingway (and visited his house). I absolutely love The Old Man and The Sea but have an aversion to The Sun Will Also Shine despite all the accolades the author received for this, his first full-length novel. The dialogue is good but reading it one is struck by it being simply a chronology of the quotidian, in this case the activities – fishing, drinking, screwing – of spoilt North American ex-pats and their lady friend in 1920s Paris and Spain. Those whom Gertrude Stein called ‘the lost generation’ – the ones who had missed ‘the excitement’ of WWI.

For example, I have no idea what this adds to the story: “I was not at all sure Mike’s rods would come from Scotland on time, so we hunted a tackle store and finally bought a rod for Bill up-stairs over a drygoods store. The man who sold the tackle was out, and we had to wait for him to come back. Finally he came in, and we bought a pretty good rod cheap, and two landing-nets.”

However, those who guard the literary canon regard the novel as fairly brilliant.

Interestingly, the novel mentions the IRA killing of Sir Henry Wilson in London in June 1922:

“Well, I went to the dinner, and it was the night they’d shot Henry Wilson, so the Prince didn’t come and the King didn’t come, and no one wore any medals, and all these coves were busy taking off their medals, and I had mine in my pocket.”

Although in a later book of non-fiction, Death In The Afternoon, Hemingway was to write an homage to bullfighting, his passion for the blood sport is obvious in this first novel with a lengthy description of the funeral of a bullfighter, followed by the ‘guilty’ bull being killed in the ring and then having its ear cut off “by popular acclamation”.

Santiago, the old Cuban fisherman, the hero of The Old Man and the Sea, sets out alone in the early hours in his little skiff – despite his companion, Manolin, a young boy, wanting to go with him. He has gone such a long time that villagers assume he has died. Instead he has caught a huge marlin, a monster, at least fifteen hundred pounds in weight and stretching eighteen feet from nose to tail. His struggle with the fish, including days and nights of hunger and exhaustion, is epic. It is a very simple story but skilfully written and affecting.

Alone and far away from home, the old man reflects on nature and life:

“Imagine if each day a man must try to kill the moon, he thought. The moon runs away. But imagine if a man each day should have to try to kill the sun? We were born lucky, he thought. Then he was sorry for the great fish that had nothing to eat and his determination to kill him never relaxed in his sorrow for him. How many people will he feed, he thought. But are they worthy to eat him? No, of course not. There is no one worthy of eating him from the manner of his behaviour and his great dignity. I do not understand these things, he thought. But it is good that we do not have to try to kill the sun or the moon or the stars. It is enough to live on the sea and kill our true brothers. Now, he thought, I must think.”

Later, he says: “You did not kill the fish only to keep alive and to sell for food, he thought. You killed him for pride and because you are a fisherman. You loved him when he was alive and you loved him after. If you love him, it is not a sin to kill him. Or is it more? …

“Besides, he thought, everything kills everything else in some way. Fishing kills me exactly as it keeps me alive.”

Describing the book, Hemingway said: “It’s as though I had gotten finally what I had been working for all my life.”

It won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. Part of the citation stated: “for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style”.