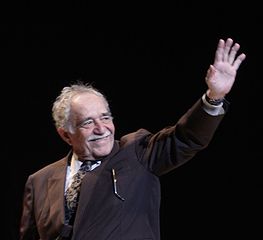

It opens with his mother and ends with a letter from his lover! ‘Living To Tell The Tale’ by Gabríel ‘Gabo’ Garcia Márquez, first published 2002 and translated by Edith Grossman is a wonderful read, full of insights and quotes. For example, this one attributed to George Bernard Shaw: “From a very early age I’ve had to interrupt my education to go to school.” And this to Lenin: “If you do not become involved in politics, politics will eventually become involved in you.”

His parents desperately wanted him to be a professional and go to university which was denied his father but he just wants to read and party! One day, when he is eighteen, his mother comments: “they say that if you put your mind to it you could be a good writer.”

As school he was terrible at spelling – and still is today, relying on his editors to correct his mistakes! “I never could understand why silent letters are allowed, or two different letters with the same sound, and so many other pointless rules… Even today, when I have published seventeen books, my proofreaders honor me with the courtesy of correcting my spelling atrocities as if they were simple typographical errors.”

Reading this book is a real insight into the provenance of many of ‘Gabo’s’ novels, as he himself explains. When he was writing ‘Love in the Time of Cholera’ and a particular scene he asked his father if there was a specific word for the act of linking one office to another. His father as a young man had been banned from seeing his future wife – as a telegraph operator he had been deemed socially below her. But he had thwarted her parents by keeping in touch with Marquez’s mother through complicit colleagues.

“He did not have to think about it: pegging in. The word is in the dictionary, though not with the specific meaning I needed, but it seemed perfect since communication between different offices was established by connecting a peg on a panel of telegraphic terminals. I never discussed it with my father. But not long before his death he was asked in a newspaper interview if he had ever wanted to write a novel, and he answered that he had but gave it up when I asked him about the verb pegging in, because he realized then that the book I was writing was the same one he had planned to write.”

His Aunt Mama (Francisca Simodosea) made cigarettes out of harsh tobacco which “she smoked backwards, with the lit end inside her mouth, as the Liberal troops did so as not to be seen by the enemy in the dark of night.”

I remember when I first read a similar account in ‘Cholera’ that I thought he had made it up and that it was meant to be an example of magic realism and had some significance which I failed to appreciate!

A policeman once caught him having an affair with his wife and could have killed him with his regulation gun but relented. This incident became material: “I always believed that Nigromanta’s husband was a good model for the military magistrate in ‘In Evil Hour’, but while I was developing him as a character he was seducing me as a human being, and I had no reason to kill him, for I discovered that a serious writer cannot kill a character without a persuasive reason, and I did not have one.”

Another one with whom he fell in love with, Maria Alejandrina Cervantes, disappeared from his life. “Years later I rescued her from my memories, not so much for her charms as for the resonance of her name, and I revived her, to protect another woman in one of my novels, as the owner and madam of a house of pleasure that never existed.”

Regarding sources he says, “there is nothing in this world or the next that is not useful to a writer.”

On Joyce – “… James Joyce ‘Ulysses’, which I read in bits and pieces and fits and starts until I lost all patience. It was premature brashness. Years later, as a docile adult, I set myself the task of reading it again in a serious way, and it not only was the discovery of a genuine world that I never suspected inside me, but it also provided invaluable technical help to me in freeing language and in handling time and structures in my books.”

On Joyce – “… James Joyce ‘Ulysses’, which I read in bits and pieces and fits and starts until I lost all patience. It was premature brashness. Years later, as a docile adult, I set myself the task of reading it again in a serious way, and it not only was the discovery of a genuine world that I never suspected inside me, but it also provided invaluable technical help to me in freeing language and in handling time and structures in my books.”

It and ‘The Metamorphosis’ were “mysterious books whose dangerous precipices were not only different from but often contrary to everything I had known until then. It was not necessary to demonstrate facts: it was enough for the author to have written something for it to be true, with no proof other than the power of his talent and the authority of his voice.”

Pasquines – anonymous scandal sheets that were posted in public and disclosed horrifying secrets – real or invented – even in the least suspect families.

On journalism – “set me to thinking for the first time about the possibilities of journalism, not as a primary source of information but as much more: a literary genre. Before many years passed I would prove this in my own flesh, until I came to believe, as I believe today more than ever, that the novel and journalism are children of the same mother.”

On short story versus the novel – “Many of the novels I was reading then, and which I admired, interested me only because of their technical lessons. That is: their secret carpentry. From the metaphysical abstractions of the first three stories to the last three of that period, I have found precise and very useful clues to the elementary formation of a writer. The idea of exploring other forms had not even passed through my mind. I thought that the story and the novel not only were different literary genres but two organisms with natures so diverse it would be fatal to confuse them. Today I still believe that, and I am convinced more than ever of the supremacy of the short story over the novel.”

On words – “each word ought to be responsible for the entire structure”.

On early rejection – “And so I faced without witnesses the unadorned notification that ‘Leaf Storm’ had been rejected. I did not have to read the entire verdict to feel its brutal impact and know I was going to die then and there…

“In other conversations that I had at the time, I was comforted by the precedent of Guillermo de Torre rejecting the original of Pablo Neruda’s ‘Residence on Earth’, in 1927.

Mentions – a writer called William Irish whom I had never heard of before. His real name was Cornell Hopley-Woolrich and American novelist whose biographer rated him the fourth best crime writer of his day, after Dashiell Hammett, Erle Stanley Gardner and Raymond Chandler. Mentions that he went to university with Camilo Torres (who later became a priest, then a revolutionary with Colombian guerrillas and was killed in action in 1966); Andre Gide’s ‘The Counterfeiters’; Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ‘The House of the Seven Gables’ “which marked me for life”; and mentions Alejo Carpentier’s ‘The Kingdom of This World’.