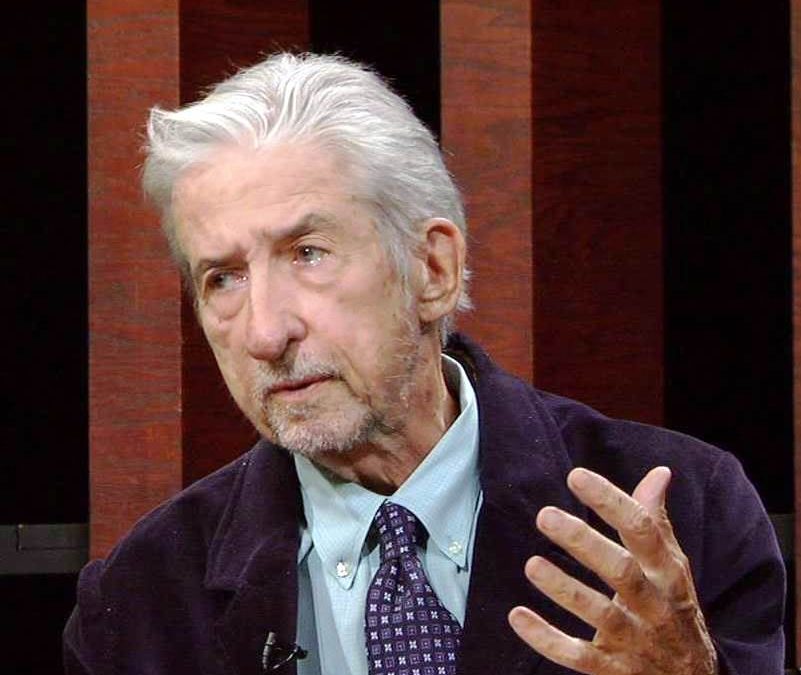

The Irish-American activist, Tom Hayden, died in October 2016 – his death an incalculable loss to the struggle for civil rights, justice and freedom, peace and democracy.

I first met Tom forty years ago when he was visiting Ireland with his young son Troy. They stayed with my wife Sandra and I in Beechmount for several days, and ever since then we kept in touch with each other.

He was a fascinating person to be with and to listen to and learn from. His involvement in the civil rights movement in the US is legendary: his was the voice of a new generation which opposed the war in Vietnam and espoused radical politics, challenging prejudice, discrimination and justice both domestically and internationally.

He wrote several influential books on Ireland, including Irish Hunger (1997) and Irish on the Inside (2001). As a former California state senator, he passed legislation incorporating the Great Hunger into the public school curriculum used by 500,000 students, and co-authored California’s Mac Bride Principles. He was an advisor to the US Commerce Secretary Charles Meissner during his economic mission to Ireland in 1997 and was a regular visitor to Ireland and to my home since.

Last August, John McNally, a friend of Tom’s, gave me Tom’s final book, Hell No – The Forgotten Power of the Vietnam Peace Movement, and what a book it is!

Back in the early 1960s Tom was a founder of Students for a Democratic Society. Later, as a civil rights activist he was beaten in Mississippi and jailed in Georgia. In 1968 he had to defend himself against charges that he had organised riots at the Democratic National Convention over the party’s stance on Vietnam.

Hell No is a handbook for activism, for peaceful protest, for how to organise and develop a mass movement, and it is dedicated ‘To the millions who protested the Vietnam War.’

For putting his head above the parapet, for engaging with North Vietnam (which he visited four times), Hayden suffered arrests and assaults, was demonised, called a traitor and a communist fifth columnist. At a personal level his father, a World War II Marine, disowned him for sixteen years and he was cut off from his younger sister. His mother, he says, “virtually lived in hiding every time my name was in the news.”

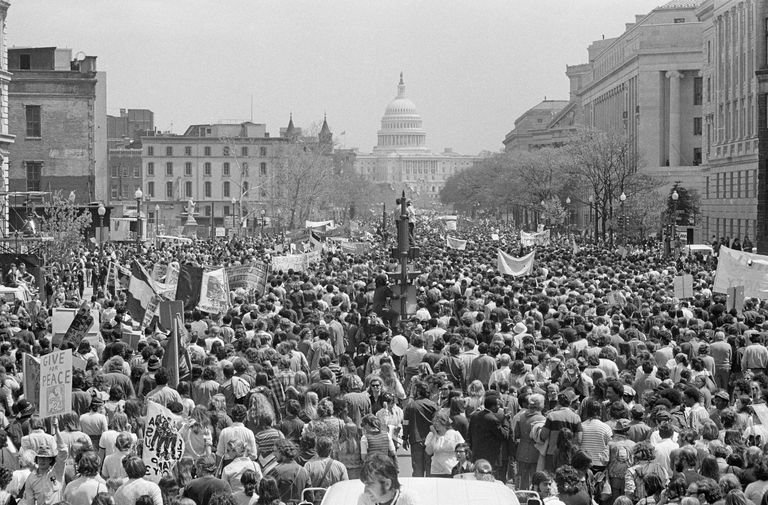

Hell No, takes its name from the battle cry of the largest peace movement in American history – the effort to end the Vietnam War which brought millions of people onto the streets.

The book describes the crucial role of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (something one would like to see effectively emerge in Israel regarding Palestine) and sets out “to reverse the propaganda about Vietnam and our movement to end the war. It is time for truth-telling, for healing, and for legacy.”

Student campuses were often to the fore in the protests – a hundred demonstrations a day, often monitored and surrounded by aggressive National Guardsmen. Twenty nine young American college students were killed by state forces and their proxies. Eight Americans burnt themselves to death in protest, including, in 1965, an 82-year-old Quaker, Alice Herz, of German-Jewish ancestry who had fled Nazi Germany in 1933; and 31-year-old Norman Morrison, another Quaker, who set fire to himself outside Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s Pentagon office. There were also hundreds killed in black urban insurrections as black youths were conscripted. There were revolts within the ranks – 1,500, often fatal, (‘fragging’) attacks by GIs against their officers; ‘riots’ on military bases; 40,000 desertions to Canada and Sweden; and 10,000 soldiers went underground. Over 3,000 conscripts were imprisoned; thousands more GIs court-martialled.

The enemy – the Vietnamese – were dehumanised so as to make killing them (and raping the girls and women) much easier. They were Gooks, goo-goos, slopes, ants, dinks, zipperheads, slant-eyes, yellow ones.

Fifty eight thousand Americans lost their lives in South East Asia but the price paid by the Vietnamese – who never once threatened American soil or its citizens – was multiples of that and affected every child, woman and man (and to this day). Figures vary but as many as two million civilians were killed. Villages were napalm-bombed and peasants were often massacred. Over one million North Vietnamese fighters and their allies in the southern National Liberation Front died. South Vietnamese dead included the 300,000 soldiers who allied with the US against their brothers and sisters to maintain partition. They are not recognised under US law because that would qualify their families for death benefits.

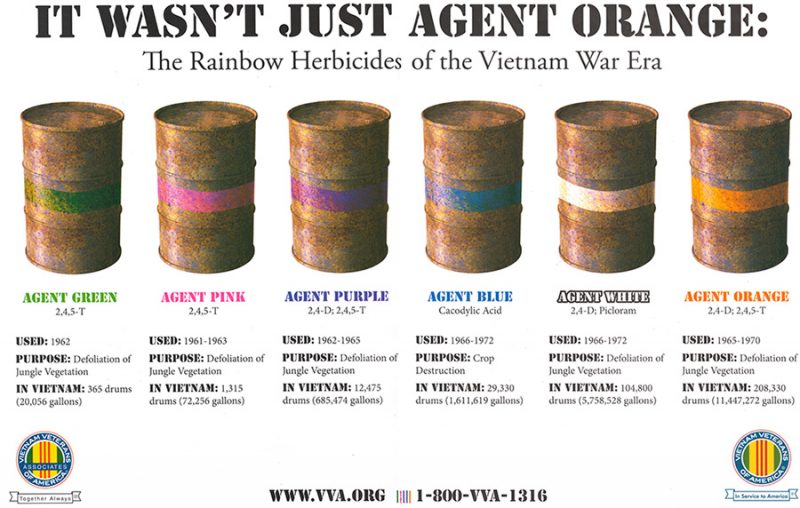

In total, the US dropped 7.8 million tons of bombs on Indochina. (In comparison, the total Allied bombing of the white Axis powers in WWII was 2.7 million.) They also dropped 20 million gallons of dioxin-laced Agent Orange and other defoliants which has led to immense suffering and birth deformities to this day. Since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 (or, ‘The American War’, as the Vietnamese more correctly put it) more than forty thousand Vietnamese have been killed by unexploded ordnance.

The US was forced to withdraw, South Vietnam collapsed and Hanoi became the capital of the re-united country with Saigon being renamed Ho Chi Minh City. Despite the US and Vietnam normalising relations in 1995, and the US reneging on paying $7 billion promised to Vietnam under the Paris Peace Agreement, the Vietnamese people appear not to be bitter, to be extremely forgiving. Indeed, one poll showed that a vast majority held a favourable view of the USA. There are many examples of US veterans going back and bonding and establishing deep friendships with their former enemies.

I myself, last year, saw just how friendly the people were. But despite pride in their patriotism, their fortitude and ultimate victory, few wanted to talk about the conflict – or, ‘the sorrow of war’, as lyrically put by former North Vietnamese soldier and author Bao Ninh. There is still widespread poverty and an understandable rise in materialism on a very long road to recovery, especially under the economic reform programme, Đổi Mới. Our tour guide (whose father, he later admitted, had been a medic attached to the Marines and was now domiciled in the US) insisted on calling the Revolutionary/Reunification Palace by its old name, The Presidential Palace (home of the US puppet president).

In the United States, during the war, 20,000 full-time FBI men monitored domestic protestors. Political dossiers were kept on eighteen million civilians and there were contingency plans to detain war protestors in camps.

Of course, thousands of informers had also infiltrated the anti-war movement to disseminate counterintelligence programmes and to exploit and heighten divisions that were already there – divisions “along the lines of class, race, and gender; civilian resisters and rebels within the military; street protestors and politicians; advocates of nonviolence, electoral politics, disruption, and resistance. These different factions often quarreled bitterly, some at the instigation of the FBI but also due to ego or sectarian and ideological rivalries among our ranks,” says Hayden.

Still, Hayden and the people whom he joined on the streets, on the campuses, did bring the war to an end. And what an atrocious, bloody and unnecessary war it was.

Up until the rise of Trump, the hand of the US was somewhat stayed by the memory of that mass movement. Ironically, one offshoot of this circumscription, has led the US military to conduct warfare by unmanned drones, being able with impunity and immunity to kill people from an office thousands of miles from ‘the front’.

Hell No is an important record of how people curtailed the mad Nixon and the power of the industrial military complex. It is a book whose relevance grows with every provocative and threatening utterance that comes out of the mouth of Donald Trump.

And I only wish Tom was still here so that I could tell him what a wonderful and important book he has written.