Today, the CIA torture report has been published. Forty-three years ago, in 1971, Irish nationalists and republicans were subjected to similar torture. Back then, the Irish government took Britain to the European Court. In the first phase of the inquiry, the European Commission found Britain guilty of torturing prisoners. This, of course, after much ‘diplomacy’ was later finessed into a European Court ruling that Britain had subjected a group of internees to ‘inhuman and degrading’ treatment only, because they didn’t mean to torture the men and derived no pleasure from it!

Documents that were unearthed in 2014 showed that British government figures had lied to the European Court and that Britain had sanctioned torture and sanctioned the cover-up. Last week, the Irish government asked Europe to re-open the case in the light of these new revelations.

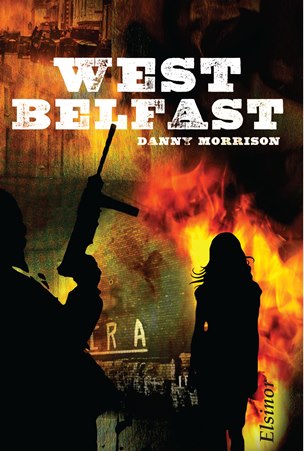

My novel, West Belfast, written 25 years ago and which is being re-issued in January, includes a chapter where one of the main characters, John O’Neill, is arrested and is one of the hooded men. It is fictional, of course, but before I wrote it I interviewed three of the hooded men to get a sense of what they experienced:

My novel, West Belfast, written 25 years ago and which is being re-issued in January, includes a chapter where one of the main characters, John O’Neill, is arrested and is one of the hooded men. It is fictional, of course, but before I wrote it I interviewed three of the hooded men to get a sense of what they experienced:

AUGUST 9th, 1971

Before John had time to recognise the crashing sounds, the noise of boots on the stairs and Sheila’s and Monica’s screaming, the paratroopers came in on top of him. They had sledge-hammered the front and back doors and had left their armoured cars on the main road to ensure surprise. Raymond was away in England and Jimmy was staying in his granny’s house so there was no disputing who – Peter or John – was the 23-year-old.

“What’s going on? What’s going on?” demanded Peter.

“Never you mind, old man. John O’Neill, I’m arresting you under the Special Powers Act. Tie him up!”

Catherine was shaking, Monica and Sheila were crying.

“Leave him alone! Leave him alone!” his youngest sister protested but she was pushed aside.

His hands were tied behind his back and a rope put around his neck.

This was the price that had to be paid, John kept thinking, but cursed himself for being at home having chided the others who had fallen back into the habit of creature comforts. If only the house had been raided in July then I wouldn’t be here now, he thought.

Peter ran out into the street and stuffed a packet of cigarettes into John’s trouser pocket. But the escort wouldn’t accept John’s shoes and socks. Though it was still dark, people had gathered and were shouting abuse at the soldiers. There was a sudden, hushed silence when the noose around John’s neck was tightened and he began choking.

“Get your bin lids out and start rattling!” shouted a neighbour, Peggy Carson. Another, Mrs Clarke, comforted Catherine. John was made to lie on the floor of the armoured car, soldiers’ boots on top of him.

“What about Donnelly?” he heard an officer ask.

“We missed the bastard.”

They arrived at Mulhouse Street Barracks. He was taken inside and roughed up. Radios were crackling, and Armoured Personnel Carriers were arriving and departing in a frantic commotion of shouting, cursing, and horns being blasted. The place tasted of fear. He was brought into what appeared to be an assembly hall where there were many other prisoners similarly bound. A soldier was appointed to each prisoner.

There was a loud explosion close by; probably a nail bomb, thought John. They had planned what to do when internment was introduced. As soon as the crowds came on to the streets the units would begin moving weapons out of dumps. They were to attack the soldiers and demonstrate that the IRA was still intact; but it was also part of the plan to move the struggle onto a new level.

The sun came up to reveal in the sky palls of black smoke rising from nationalist areas as the rioting spread. John was bundled out of the hall and placed on plank seating with others in the back of a canvas-covered lorry. Of the eight prisoners only John was an IRA Volunteer, while a few were supporters and the rest had a small local profile in street politics. The lorry drove out of the base and turned down the Grosvenor Road. Shooting from the Leeson Street area could now be heard. The soldiers fell quickly to the floor but jabbed the muzzles of their rifles into the prisoners forcing them to sit upright.

“Boys, this is Pocky Logan, Pocky Logan! Don’t be shooting! Hold your fire!” shouted a prisoner sitting closest to the back flaps. John felt disgusted at the spinelessness and noted that the soldiers who had slapped them for asking questions or speaking earlier didn’t interfere or interrupt Logan’s screams.

At Girdwood Barracks John was thrown out of the lorry. There was a queue of silent prisoners waiting to go into a gymnasium. Many were badly injured, blood pouring from head-wounds. One complained that his fingers were broken and was struck with a baton across the shoulder blades. There was an old man, stiff in his movements, who had just received a black eye from a military policeman for refusing to comply with an order. Another soldier protested at him being hit.

“This is feckin’ desperate, corporal. Look at ’im – he’s only an old man.”

“Mind your own business and carry out your orders,” said the Military Policeman, who was his senior.

In the gymnasium several hundred prisoners were sitting on the floor, some in pyjamas, with their hands on their heads. The Military Policemen were in control. Fractious detainees were hit with batons and ordered to do press-ups. Names were called out and then those persons were marched out to interrogation rooms.

John’s wrists were still behind his back. He was photographed and taken to a room for questioning. As he approached the room he heard a loud groan. Two RUC men in plain clothes, whom he took to be Special Branch officers, were interrogating a prisoner who was handcuffed and hanging from a round iron bar cemented into the wall. On the other wall was a framed colour picture of Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, smiling.

“No more, no more, please! I’ll talk. Let me down, please!”

The fear in the room was palpable but John was suspicious of the quasi-crucifixion. Activity in the room had only begun when he was a few yards off and there was too much blood on the prisoner’s face. He had heard from old republicans about being put in the same cell as someone who would claim to be from another IRA Brigade area but who was actually a plant, trying to get information. He decided that this was a set-up.

One of the RUC men flicked through a thick file: “Ah, so you’re John O’Neill. Take him away!” He was surprised that that was all that was said. On the way down the corridor he had to pass MPs who were standing about.

“Here’s the bastard that shoots our mates in the back!” one shouted. They began punching and kicking him. He ran as fast as he could but two of the MPs had their arms through his and they slowed him down. He was put back on the floor. The beating had helped restore his faith in his convictions. The bruises were sore but he was not bleeding and he stared ahead of him, curiously enjoying the thought of a cigarette, inhaling the stream of blue smoke like it was an intoxicating draught. He was also more anxious about his family than about himself because at least he knew what to expect.

The cord around his wrists was cut off and he was ordered up off his feet and taken to the toilets. “Here, clean them!” he was told. He let the scrubbing brush fall to the ground.

“Clean them!” the voice roared – bad breath – inches from his face. John refused, was punched in the stomach and grabbed by the scruff of the neck. He was flung to the floor and caught some of the kicks before they did him harm. He was brought back to his previous position. Hours passed. The prisoners were called up to a table for tea. There were only about twelve cups for the entire hall and the fact that they were being re-used without being washed put John off. Since his days at sea he had a fastidious attitude towards delph and cutlery but he was so thirsty that he drank the awful concoction. Out of the side of his eye he caught sight of other prisoners washing windows, brushing the floor and two carrying mops and buckets out of the toilets.

“O’Neill! Out here!”

“Cah! Out here!” When prisoner Kerr realised he’d been called he wasn’t long responding. Another four were ordered out. John was escorted out the door into the daylight and fresh air.

“Hands out front!” He was tied with plastic cuffs.

The engines of a Wessex helicopter were started up and the men were ordered to climb in. John was last. Behind them the doors locked like a vacuum seal. They took off and the flight lasted about fifteen minutes. An MP grinned at John.

“Can you swim?” he shouted. “I said, can you swim?”

John nodded.

“Well then, can you fly?” The prisoners were worried. “Did you ever see the Viet Cong getting thrown out of the choppers? Eh? That’s what’s gonna happen to you fuckers.”

The door roared open and air shot in. John was kicked out and his heart gave one last hard pump, but he fell only a few feet into a dog compound where whorls of faeces sat like deposits of giant lugworms. The other prisoners landed beside him and the helicopter quickly rose into the sky. Snarling Alsatians came running at them and the prisoners formed a group with their backs against each other, kicking at the animals who were on leashes staked beside their kennels, but long enough to present a danger. A gate opened and handlers rushed in, grabbed the men by the hair and trailed them through the barking dogs. Other soldiers, standing about as observers, shouted their approval of what was happening.

The men were taken back into the gymnasium where the number of prisoners had significantly fallen. They were then individually called for stew which turned out to be cold. It was covered in a white layer of grease and was unappetising. Anyone who refused to eat was beaten, so John was again pummelled.

His name was called. An MP grabbed him and frog-marched him out of the hall. He was taken into a large hole, which soldiers had blown in the wall dividing Girdwood Barracks from Crumlin Road Jail, and was led through. In the basement of D wing his hands were untied. The RUC found the cigarettes and confiscated them. John’s watch and ring had already been stolen.

“These will be placed in this bag outside your cell and you can collect them when you’re going,” an RUC man said, whilst a prison warder locked him up in a cell. John was jubilant and was singing to himself, “I’ve survived! I’ve survived!”

His cellmate stared at him: “My God, what have they done to you?”

The young man, whom John didn’t know, tore some linen from the bed, wetted it with water and washed the wounds. He rinsed out the makeshift flannel in the cup which instantly turned bright red. John thanked him. He then realised the extent of his injuries. His lips were split open and the air was like acid eating at them. Both eyes were black, one was almost closed over. Blood had clotted on his scalp and had dried over the skin creases. The door was unlocked and an RUC officer appeared.

“You, get out! You shouldn’t be in here with him!”

He was left on his own and pondered over what sort of arrangement was it that had RUC men and MPs in charge of prison warders, telling them where to put prisoners and when to open and close the cells. The door creaked open again. He recognised a senior officer in the Special Branch. He had been shown his photograph. The IRA had been planning to kill him. They had nicknamed him the Bouncer. The Bouncer introduced himself.

“You must know where there’s a few guns knocking about, John, my old friend. I’m not after names, just guns and bombs, you know the sort of things. I want you to think about it, son. You look like a nice fella. I know everything about you but I’m a reasonable man. There’s £20,” he said, extricating two £10 notes from a thick wad. “No, just you think about it. There’s plenty more where that came from, as you can see. I’ll call back later after you’ve rested.”

John placed his ear to the door and listened carefully until the Bouncer had finished his rounds. Then he banged on the cell door until a warder opened it.

“Any chance of a smoke?” he asked. “I’ve fags just sitting outside in a brown bag.” The warder gave the bag a glance.

“Piss off.” He proceeded to close the door.

“Wait, wait, wait! Just a minute!” John dug his hands deep into his pocket and pulled out the two £10 notes. “This is no use to me in here. Here take them, go ahead, but give me a smoke.”

“Let’s see,” said the jailer. “Okay, what’s the harm.” He gave him the packet, lit him up one of the cigarettes and pocketed the money in his breast pocket, fastening the silver button. The barefoot prisoner lay back on his bed, one leg over the other, smiling at the high, yellow ceiling.

When the Bouncer returned John had enough smokes for a week.

“Well, have you thought about it?”

“I’ve thought about it and I’m not interested.”

“You’ll be sorry. I have something special in mind for you. You’re one of the lucky ones. Now, give me my money, I mean, our money back.”

“I haven’t got it.”

“Where is it then?”

“He has it,” said John pointing. “That screw has it in his top pocket. I gave it to him to mind for you.”

The warder began stuttering.

“Oh yes, here you are, sir, here you are.”

“Why wouldn’t you take the money?”

“Money wouldn’t buy my pride.”

“Well, you’ll have plenty of time to think about your pride.”

All that night the lights were kept on and the cell doors were banged. It was only possible to lightly doze.

On Tuesday morning MPs took John out of the jail and forced him to run an obstacle course made of barbed wire and broken glass. He was once again confused and afraid because he had thought it was all over once he was in jail. His moods swung between spiritual highs and demoralised lows.

What if they’re right and I’m wrong? Could we really have expected to take on the British government without retribution? Were we upstarts, dreamers, doomed from the outset? Then he would draw upon his convictions which were buried under the weight of the brutality, and he felt an inner peace. I am right, I am right! he said aloud.

And when they saw the trace of that defiant smile they beat him all the more.

Late on Tuesday night, shaken and hungry, he was brought outside into the darkness. There were three other prisoners whom he recognised but did not acknowledge. Their hands were tied behind their backs with plastic cord. The MPs stood in front of them, silently. Slowly and deliberately they produced eight hoods – hessian-type bags – and put one hood inside the other. Then they walked behind each prisoner and pulled the hoods over their heads. The man on John’s right began to scream and he heard the dull thuds of fists pile-driving into a stomach. The terrified prisoner quietened down after that.

Someone twisted the bag at the back until it tightened and John felt as if he was choking. A helicopter landed and they were pushed and kicked on board. Within seconds it took off. It flew for over three-quarters of an hour. When it came to ground they were again kicked and forced to run over rough terrain. The length of the journey made John think he was in England or Scotland.

He was brought into a brick building. The floor was cold and bare. From the echo of his escort’s boots he felt that they were going down a corridor. He was brought to be medically examined. He could hear the doctor turning in a swivel chair.

“Any ailments?” said the doctor. He was English. John guessed he was fat, from the compression in his voice.

“I’ve a bad heart,” said John.

“Uncuff him and take his clothes off.” He cursorily examined him. “He’s all right for interrogation.”

The hood was wrenched tight and he was forced out of the room. He was bundled into a boiler suit, two sizes too big for him.

“Up against that wall!”

He didn’t understand the order because of a loud hissing noise and was forcibly spread-eagled by two or three people with English and Scottish accents. He tried to reduce the angle by a few inches, and thus ease the pressure on his limbs, but his feet were kicked even further apart.

“Now, maintain your posture or else …”

Hours dripped by and he felt as though a snow-plough went through his brain, scattering cells, splattering red flakes into the ditch, returning and churning up more furrows, shaving his brain smooth, opening the road to allow the interrogators’ traffic through.

“What time is it?” he asked.

“It’s August and don’t you leave that wall!”

He fell and was beaten, then he was helped into the spread-eagle position and told: “Resume the posture!”

More hours passed by.

“Come with us.”

He was taken into a room. The hood was removed and a number of men sat behind arc lights which were trained on him where he stood.

“You asked to see us.”

“I didn’t ask to see you,” he whispered.

“What did he say?”

“He said he didn’t ask to see us.”

He was hit across the head and fell on the concrete floor, but got on to all fours. His interrogators wore track suits and plimsolls and their faces were hidden. He was frog-marched back to the wall.

“Resume the posture!”

Hours passed. More beatings each time he fell. The noise drove excruciating pain through his head.

“Can I go to the toilet?” he asked.

“You are shit, so shit where you are!”

He had no bowel movements and had been given no water. He dreamed he was urinating against an entry wall and urine dribbled down his leg, hot and stinging, chafing his thigh, and he was reminded of dribbling as a child when he thought he had finished.

“Out!”

Corridor. Room. Lights.

“You asked to see us?”

“I didn’t ask …”

Another beating. Back to the wall, back to the Devil’s screech.

“Out!”

Corridor. Room? No room. Air. Lorry. Drive. Helicopter. Sky. Earth. Jeep.

“Get him through the hole in the wall.”

Crumlin Road Jail?

The hood was removed. Three RUC officers sat in front of him.

“Are you John O’Neill?”

“Yes.”

“Here is a removal order empowering the RUC via the Civil Authority to remove you to any place where your presence is required and question you for any length of time. As you can see it has been signed by the Minister of Home Affairs, Mr Brian Faulkner. Okay? Here you are.”

It was stuffed into the top pocket of the boiler suit.

He was taken back out through the hole in the wall, hooded, placed in a jeep, driven to the helicopter, flown to the place of interrogation and was soon back up against the wall in the spread-eagle position.

Hours. Hood removed.

“You asked to see us?”

– Silence.

“I told you he asked to see us, didn’t I!”

“Yes, you did! Do you think is he ready?”

“I don’t know. Let’s ask. You did ask to see us.”

His convictions were hanging on to the edge of a cliff with one finger nail. You were a tout before, O’Neill. Are you going to be a tout again? What about Paul McShane? Paul McShane . . . Paul McShane, McShane, the shame; the shame of squealing on McShane. School days, so long ago, so innocent, before all this. He hauled his mind up from where it perilously dangled, used the pause, the silence, as breathing space and muttered: “I didn’t ask to see you …”

“Fuck you, O’Neill!” The lamp was knocked over and one of the figures kicked him in the groin. The whole world went dark.

…………………………

“Where’s the guns?”

“Where’s Stevie Donnelly?”

“Where’s Dominic Gallagher?”

“You blew up the jeep in Brougher Mountain!”

“You killed the three Scottish soldiers!”

“Two of them were brothers, you bastard.”

“Yeh, and seventeen years of age.”

“You blew up Roden Street Barracks!”

“You blew up Sergeant Wallace in Springfield Road!”

“You planted incendaries in Anderson and McAuley’s!”

“Where’s the guns?”

“Where’s Stevie Donnelly?”

“Where’s Dominic Gallagher?”

Some of the questions and statements meant nothing. He wasn’t talking but most of the time there would have been no time to have answered before the next question or statement came.

“You blew up Roden Street Barracks!”

“You blew up Sergeant Wallace in Springfield Road!”

“You planted incendaries in Anderson and McAuley’s!”

“You blew up Bronco McIvor!”

“Outside his house! That was nice!”

What? What was that? Did he hear that? John wanted to tell them that they had got it all wrong, that he didn’t blow up Bronco. They had worked together. Shared cigarettes. Had become friends. Bronco wanted him to stay. Not go on the boats. But then he knew that that was a lie. Was there a police reservist called Bronco blown up in his car? Whatever the truth, John now experienced a mix of emotions as if he were just learning for the first time that his comrades killed Bronco, old Bronco McIvor with the King Billy tattoos, who had gone on to join the Police Reserve, who wasn’t just a mouthpiece, who somewhere along the line, because of a word or a deed or an emotion, had been tipped over the edge… like John.

Did they know they had shaken him, might have had him? They could see his face because the hood had been removed. But they could not read the expression of sadness and regret beneath the blood and bruising.

“Do you want to go back to the music room, John?”

The music room, that’s what they called the room where the high-pitched hissing sound, the ‘white noise’, went on and on and on.

Days passed, days of more blood and bruising.

John turned the minute hand of the chubby alarm clock back, to give the workers an extra half-hour to get out. Stevie covered the doors. As John ran to make their escape Stevie dropped his gun and grabbed him in a bear hug, like a madman.

“For fuck’s sake Stevie let me go. Let me go! This place is gonna go up! I’ve planted bombs. It’s gonna go up, up, up!”

“What’s gonna go up? What’s gonna go up?”

He awoke, handcuffed to a radiator – the rest room.

“Okay, back to the wall. Resume the posture! You’ll talk. You’ll

talk!”

The doctor saw him twice more: “Fit for interrogation!”

“Where’s the guns? Where’s the guns? Where’s the guns?”

“Where’s Donnelly? Where’s Stevie Donnelly? Where is he?”

“Where’s that cunt Gallagher? Where’s Dominic Gallagher?”

John sat at the top right hand corner of the ceiling, out of sight, impish, giggling, as they punched him in the ribs down below.

Next, he was being rolled about on the ground. They were rubbing his neck, massaging his muscles, restoring his circulation.

They lifted the hood up and he sipped some water through his parched lips. They gave him a piece of broken bread which almost choked him.

“Right. Resume the posture!”

Spread-eagled again. Legs kicked out. He tried to cheat by using his head to take the weight off his arms but they fired shots which forced him back on his fingers. He thought of his mother and she appeared before him and he felt happy. He did not feel like a person, he was either a mind or an aching, sore body, never the two together.

He felt like crying, he had just shit himself. It had been a painfully slow bowel movement and the little warm balls stuck between the cheeks of his buttocks. They gave off, he imagined, a dreadful stink and reduced him to a baby. He was helpless.

“John? John?” It was a friendly, soothing voice. “John, it’s okay. The hooded treatment is over.”

His eyeballs returned to his head. His head, arms and legs returned to his torso from the distance to which they had been kicked. He listened hard. His eyes shot from side to side within the darkness of the hood.

“It’s over, John. I’ll take the hood off in a minute and tidy you up but I’ll have to put it back on when you move back to Crumlin Road Jail. These people don’t want you to know where you are or to see their faces. Okay? Now, take it easy …”

It was a Belfast accent. He was worried that his mind was playing a trick on him. The RUC man’s assurances made him even more afraid. The hood did come off and John stood trembling. He couldn’t move his arms. His legs were cramped in a standing position.

“Come on. I’ll help you. It’s over. You have my word. I’ll be travelling with you.”

John burst out crying as he shuffled barefoot down the corridor and into the toilets. His ankles, knees, were swollen, his hands, wrists, elbows and shoulders were in great pain. His friend shaved him, cleaned and wiped his backside. He rubbed and softly chopped at his arm and leg muscles.

“John you have to be photographed. Come with me. It won’t take long.”

He was photographed in the nude and the cameraman appeared to be hundreds of yards away in the distance. He was taken back to the corridor. He couldn’t talk but hung on to the man who was showing him mercy. He held onto him when he thought he was leaving him.

“Look. It’s okay. It’s time to go. Trust me. Help me put on the hood. We’ll do it together. That’s it. Now, I have to handcuff you. Then we’ll get on board the helicopter. When it lands I’ll remove the handcuffs and the hood but don’t look back. You’re going away from here, back to your mates. When you go to jail there’ll be a tribunal. You’re not a bad fella, you know. After thirty days you’ll be able to go to this tribunal and sign a form and you’ll be out. If I ever meet you in the street would you buy me a drink?”

John spoke for the first time: “I’ll buy you all the drink you want.”

“We’re going now.”

When the helicopter landed the policeman said: “Don’t be looking back. Good luck,” and he pulled the hood off and pushed him out. The doors whooshed closed and other RUC men put him into the back of a Land Rover and then drove him to the jail.

He was brought into the basement of D Wing. The prison doctor weighed him. He had lost 16 lbs.

“What day is it, doctor?”

“It’s Tuesday.”

“It couldn’t be. I was here on Tuesday. It must be Thursday or Friday.”

“No. It’s Tuesday, Tuesday the 17th August.”