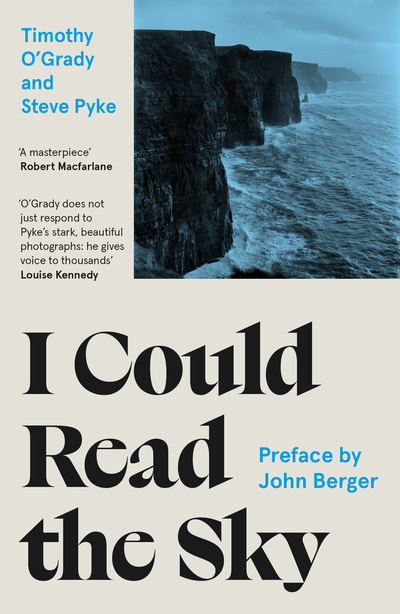

Tim O’Grady and Steve Pyke’s photographic novel, I Could Read the Sky, first publsihed in 1997, has just been reissued in a brilliant new edition, along with an audiobook which combines O’Grady’s reading with a score created by fiddler Martin Hayes (who in a concert adapted from the novel in 1998 was accompanied by the late Dennis Cahill).

The novel, which has become a classic, is about an Irishman exiled in London, told through words and Pyke’s haunting photographs (with many which were not included in the first edition). It was also adapted for cinema by Nichola Bruce and featured writer and poet Dermot Healy, who died in 2014, in the lead role.

I reviewed the novel and also the 1998 concert in London for the Irish Examiner. This weekend the Examiner reviewed the new edition as did the Irish Times in a double-page spread written by Joe O’Connor.

This is what I wrote in 1998.

I Could Read The Sky

– The Emigrant’s Song

Poverty. The leaving of the native soil. The scattering. The strangeness of England. The unsettledness of the soul. The dream of coming home one day ‘in a new suit filled with banknotes.’ Never coming home. Remaining sane only through memory and the music of Ireland. The days become weeks, the months years, the decades a lifetime. Never coming home. Memory and the music of Ireland.

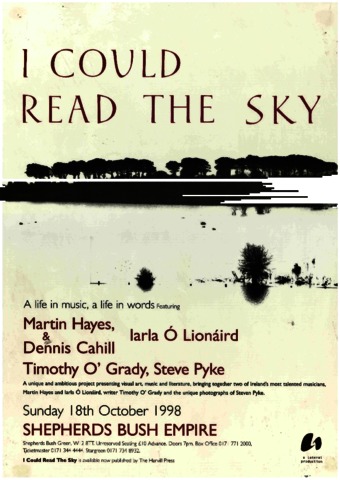

Tim O’Grady, an Irish-American and writer, spoke to the old emigrants of the forties, fifties and sixties. He was moved by their stories and he eventually mediated their experiences through the poignant recollections of an old widower, lying in his bed in a flat in Kentish Town. O’Grady’s book I Could Read the Sky has just been re-published by Harvill in paperback. For several months O’Grady was working on the idea of how to fuse prose and photographs and music. His ideas came to fruition in an amazing concert in London’s Shepherds Bush Empire last Sunday night and the audience responded with standing ovations and tears of sadness and pride.

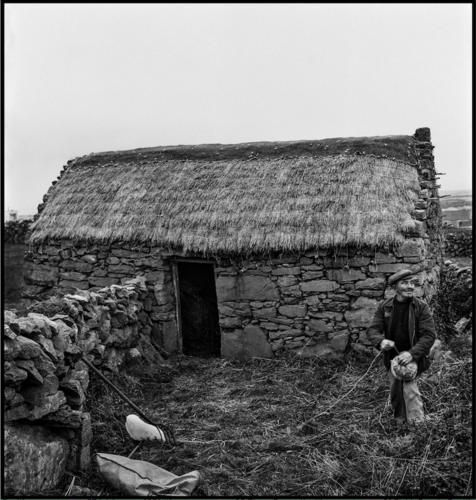

Sinead O’Connor learnt two songs in Irish for the occasion, duetting with Iarla O Lionaird. Martin Hayes flew in from Seattle, Dennis Cahill from Chicago. Steve Pyke’s haunting black and white photographs of the old country’s stark and childless landscapes showed how it was. O’Grady, in the voice of the old man, thinks back to the trades he knew back home:

‘I could mend nets. Thatch a roof. Build stairs. Make a basket from reeds. Splint the leg of a cow. Cut turf. Build a wall. Go three rounds with Joe in the ring Da put up in the barn. I could dance sets. Read the sky. Make a barrel for mackerel. Mend roads. Make a boat. Stuff a saddle. Put a wheel on a cart. Strike a deal. Make a field… Shoot straight… Set potatoes. Plough and harrow… Make a coffin. Take drink… I knew the song to sing to a cow when milking. I could play twenty-seven tunes on my accordion.’

And he thinks about what he couldn’t do in England:

‘Eat a meal lacking potatoes. Trust banks. Wear a watch… Remember the routes of buses. Wear a collar in comfort… Acknowledge the Queen… Save money… Drink coffee… Follow cricket… Speak with men wearing collars… Understand their jokes. Face the dentist. Kill a Sunday. Stop remembering.’

I travelled over to London especially for the concert. I never had to emigrate – which was very handy, given that I was excluded from England up until recent years and am still barred from Canada and the USA. But to have had to seek employment in the country historically responsible in various degrees for your economic woes must have been quite humiliating. Yet out of the experience a paradoxical love/hate relationship with the host country developed. Today’s London Irish come across as ebullient, successful and openly celebrant of their roots and culture. They have colonised and helped civilise the English!

The musical overtones to O’Grady’s lyrical novel he acknowledges as being inspired by the fiddle-playing of Feakle’s Martin Hayes, who himself was an illegal emigrant in the USA until he got his Green Card. This now-famous but humble 36-year-old, who hails from a musical family, plays with an impish smile, his hair a mass of black ringlets ceilidhing to the beat of his frenetic playing. His accompanist, Dennis Cahill from Chicago, a grand nephew of the 1917 hunger-striker Thomas Ashe, plays an acoustic guitar which alternately whispers to, disagrees with, screams at, and flirts with Hayes’ fiddle. Their act is astonishing.

Cork’s acclaimed sean nos singer Iarla O Lionaird opened the evening’s event by turning the former opera house into a cathedral with that voice of his that lingers mid-way between heaven and earth. When he sang ‘I am weary from being alone’ the audience was completely hushed. He had dedicated it to Sinead O’Connor, that doe-eyed, little faun, whose explicit sincerity makes her vulnerable to the ways of this world. Her version of ‘Raglan Road’ caused me to tremble, almost weep.

Later, when we met, and I got her to stop calling me ‘Mister Morrison’, I gave her as a present a short story I wrote about a prison orderly called Brendan Short. Shorty was serving six months for stealing a couple of pairs of jeans. We were locked up twenty-three hours a day and he used to serenade us as he mopped the landing. One of his favourite songs was Sinead O’Connor’s ‘Nothing Compares 2U’. I explained that much to her and she was genuinely pleased, though I didn’t have the nerve to tell her the ending, that someone beat Shorty to death a few weeks after his release and left his body in a deserted alleyway in West Belfast. Maybe Shorty would have had a life had he left Belfast, had he emigrated to London.

I Could Read The Sky – A Life in Music, A Life in Words was planned as a one-off, but someone should persuade the organisers to bring the event to Ireland. It was one of those rare evenings when you come away not feeling any sense of despair but with a sense of completion, that tribute has been paid, and that the men and women whose story this book tells, have not just been laid to rest, but have been resurrected.