In 2006 I was speaking at the Writers on the Wall festival in Liverpool. When I came home I wrote this feature about prisoners, but which also mentions an attempt on the life of Lloyd George one hundred years ago. Here it is:

Over breakfast at our hotel, Clive Hopwood and I talked about the panel discussion the night before and asked each other about our work. He has written almost 100 books for children and has had 20 plays performed. In recent years, he has worked in community arts and is currently the director of the Writers in Prison Network.

Over breakfast at our hotel, Clive Hopwood and I talked about the panel discussion the night before and asked each other about our work. He has written almost 100 books for children and has had 20 plays performed. In recent years, he has worked in community arts and is currently the director of the Writers in Prison Network.

I said that I would like to write a play about an old people’s home. Clive said that, years ago, he had been involved in a reminiscence project with elderly people which resulted in the publication Those Were The Days.

One old lady, Beatrice Seaton, born in Derby but retired in a nursing home in Wales, told him about her Edwardian childhood, about one of her brothers dying in infancy. Then she added: “I had one teacher who tried to poison Lloyd George.”

My eyes shot open.

David Lloyd George, the man who, on December 5, 1921, issued an ultimatum to the republican delegation, including Michael Collins, that, if they didn’t sign the Treaty before 10pm, the result would be “immediate and terrible war”.

I thought: How different would history have been had Beatrice Seaton’s teacher been successful? How different would it have been had the delegation not buckled under that threat but walked away and the Republican Movement remained united to negotiate another day?

Beatrice had told Clive that her teacher, who was a Suffragette, had sent some poisoned chocolates to Lloyd George, who was then British Prime Minster but that she was caught and went to jail. Beatrice said: “And her mother — I have in mind her mother died in jail. Suffragettes were big at the time, just before the war, and she taught us a song for a concert:

“‘Don’t forget it, don’t forget it,

Soon the ladies into parliament will go,

Don’t forget it, don’t forget it,

If they do, you’ll know!’”

In opposition, Lloyd George had been a supporter of women’s rights but did little to help the cause when he was in power.

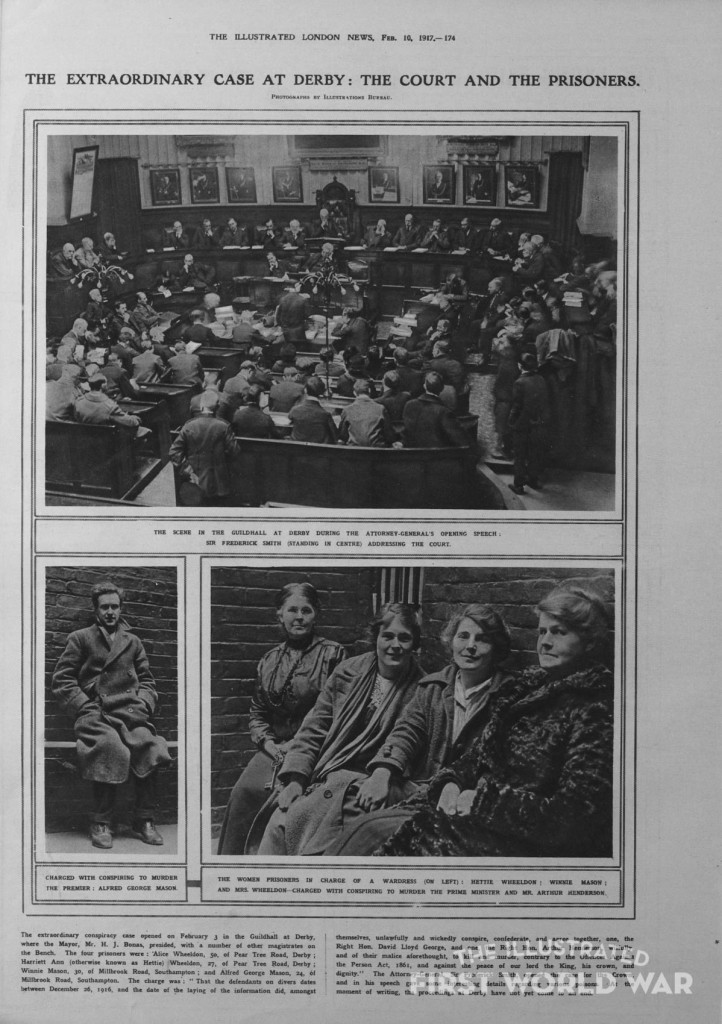

Researching the story, I discovered that Beatrice was right in the broad thrust of her recollections though she was probably referring to the case of Alice Wheeldon from Derby, her daughter Harriet Ann (who was probably the teacher), and Alice’s married daughter and son-in-law Winnie and Alfred George Mason. They were all charged with conspiring to murder Lloyd George — not with venomous Dairy Box chocolates but with poison darts. It was later alleged that the accused had been set up by British intelligence through the use of an agent provocateur and that Alice Wheeldon had been singled out because she had been hiding conscientious objectors (men who didn’t want to fight in World War I).

She was sentenced to ten years’ hard labour but was released after the war in a weakened condition. She died and was buried in an unmarked grave. Her daughter Winnie was sentenced to five years and Winnie’s husband to seven years. Harriet Ann, who had been held on remand, was acquitted.

She was sentenced to ten years’ hard labour but was released after the war in a weakened condition. She died and was buried in an unmarked grave. Her daughter Winnie was sentenced to five years and Winnie’s husband to seven years. Harriet Ann, who had been held on remand, was acquitted.

Clive Hopwood and I had shared a platform the night before as part of Liverpool’s Writing on the Wall festival. Clive, who was chairing the event on the subject of prison writings, quoted the observation of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the author of Crime and Punishment, that, “the degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons”.

There are 77,000 prisoners in jail in Britain, a state that incarcerates more people per head of population than any other European country.

On the platform were two former prisoners, George Gardiner and Ian Galtress. With little or no experience of public speaking, they bravely read out highly personal poetry, which had helped them express their inner turmoil. One — who had been six years in care — spoke about having sniffed glue from the age of eight, mutilating and trying to hang himself. “Drugs are the enemy/Don’t have a sad life”, read Ian Galtress.

The other speaker was Erwin James, who served 20 years in British prisons (but who didn’t say what his crime was) and was released 18 months ago. Writing saved James, who was barely literate when he was arrested. Without any trace of self-pity, he tells his remarkable story in two books — A Life Inside and The Home Stretch, both of which began as published pieces in The Guardian, for which James now writes full-time.

I spoke about how political prisoners coped with jail and viewed it as both university and battlefield, though they suffered the same emotional dislocation from family and loved ones and the same personal problems as all prisoners do. As I explained the blanket protest, the hunger strike, the big escape, the IRA explosion in the Crum canteen, the loyalist rocket attack the following night on the jail, the jaws of some members of the audience (and panel) literally dropped with incredulity.

James said that, for a time, he shared a wing with a number of IRA men, including Brian Keenan and Hugh Doherty. He said republican prisoners, though few in number, were in an entirely different category. Unlike the rest of the prison population, they were clearly political prisoners, a highly disciplined and motivated group, were selfless, nothing fazed them and they did time confidently.

In A Life Inside, he writes that, in jail, where any weakness is exploited, it is rare for inmates to make friends. You enter into the “precious relationship” of “true friendship” at your peril, he said.

It made me realise how lucky we republicans were, in a sense. Not lucky at having our near neighbours over for 800 years, but fortunate in that our prison history is a proud story of sacrifice, courage and defiance. Comradeships were consolidated and lasting friendships established. Within the criminal prisoner regime, the system is designed around the basis of the prisoner “accepting his or her crime and trying to become a better person”.

James writes compassionately about some of his fellow inmates but also about the norms of suicide, brutality and bullying, where it’s every man for himself in that “dark world”. One, a victim of childhood sexual abuse, self-inflicts wounds to his limbs, puts a pencil through his arm and matchsticks through his ankles, he is so full of self-loathing.

James also writes humorously and tells the story of three murderers sitting at the back in the TV room during an England/Romania match when the issue of English soccer hooliganism comes up. “Those yobbos are giving us a bad name over there,” said one, as the others nodded in agreement.

Though the prison-writing events are just a part of the overall Writing on the Wall festival, the organisers deserve credit for not balking at the unpopular subject of prisoners’ rights and the whole issue of crime and punishment, which often provokes a reactionary response from the general public.

On a lighter note, ever since Clive Hopwood told me Beatrice Seaton’s story, I haven’t been able to get ABC’s pop song Poison Arrow out of my head!