On this day in 1971 the British army and the RUC were preparing for tomorrow’s dawn raids into nationalist areas across the North, to make arrests, interrogate and intern hundreds of people even though all of the first fatalities and bombings of the Troubles/Conflict were carried out by loyalist paramilitaries, the RUC and the B-Specials. Despite the loyalist assassination campaign being at its height in 1972 no loyalist was interned until 1973. In total, almost two thousand people were interned: nineteen hundred nationalists and around one hundred loyalists.

Internment was introduced by the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) – until it lost its power with the suspension of Stormont in March 1972. The UUP was responsible for the beatings of civil rights protestors throughout 1968 and 1969 (including the attacks on students at Burntollet in January 1969), the pogroms of August 1969, the Falls Curfew of 1970 and Bloody Sunday in 1972.

The UUP was ecstatic when Labour lost the June 1970 general election to be replaced by Ted Heath’s Conservative Party. The UUP believed that with the Tories the shackles would be removed from the military and there would be a much more robust security policy. Within weeks the Falls Curfew was imposed, part of a long list of ill-fated measures used to suppress the nationalist community for the next two decades.

Some years ago, in the Andersonstown News, I wrote a feature about Ted Heath and what he was doing during the week that internment unleashed immense suffering and death upon communities across the North. Here it is.

MORNING CLOUD, INTERNMENT MORNING

I stood in front of the gates to his long driveway. The £5m house, inside a two-acre walled garden, was huge for a one-parent family (with no family), but I smirked with satisfaction at the fact that the council had forgotten to take down the sign.

When I was growing up my mother always instructed us never to speak ill of the dead.

Why should we not speak ill of the dead? Well, clearly they are in no position to defend their reputations.

But, often, neither are the living able to defend themselves, and certainly not their reputations the dispossessed of this earth, should they hail from Ballymurphy or the Bogside.

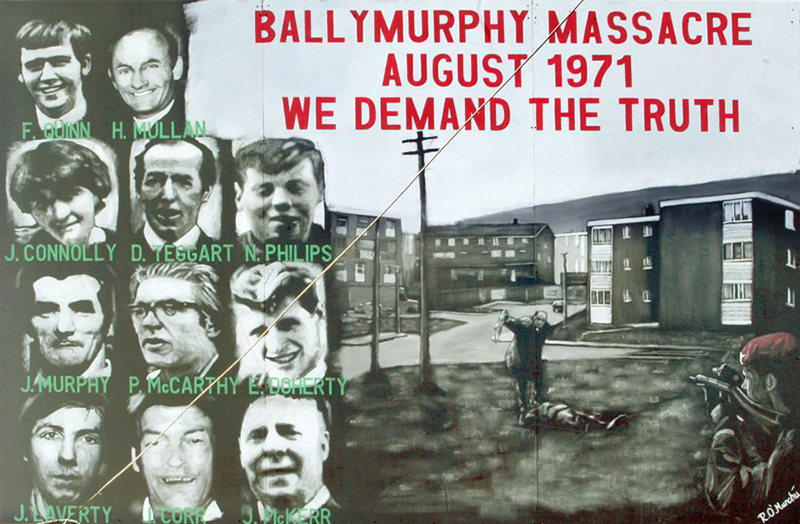

Who was there to speak out for Fr Hugh Mullan, Frank Quinn, Noel Phillips, Jean Connolly, Danny Teggart, Joseph Murphy, Eddie Doherty, John Laverty, Joseph Corr, Paddy McCarthy and John McKerr?

Surely former merchant seaman Gerry Fitt, the skipper of the SDLP and MP for West Belfast, would attest to their innocence and hound the killers of his constituents?

Those eleven innocent civilians were murdered by British paratroopers in Ballymurphy during the introduction of internment. As Paras kicked in doors, wrecked homes, made arrests, began shooting those who were in their way, the weather forecast was the most important thing that morning, Monday, 9th August, 1971

The weather forecast?

Yes, it is what preoccupied the mind of the skipper of Morning Cloud, Prime Minister Ted Heath, as the English team made the exciting return journey from Fastnet Lighthouse to Plymouth, in the prestigious six hundred mile yacht race.

It was a glorious finish.

There were cheers from the crowds of onlookers as the skipper steered the British Admiral’s Cup team to victory at the helm of his 42-foot yacht – the cumulative length of at least seven of the coffins of the Ballymurphy victims whose funerals were just beginning.

Months later, the skipper’s Paras would go on to shoot dead thirteen people in Derry protesting against internment. This was a bit embarrassing so he appointed his Lord Chief Justice Lord Widgery to have a look at things and explained to him that “it had to be remembered that we were in Northern Ireland fighting not just a military war but a propaganda war”.

In response to internment the SDLP called a rent and rates strike, joined in civil disobedience, participated in ‘illegal’ marches, and said the party would not enter into talks with the British until internment ended. After Bloody Sunday its deputy leader declared that it was now “a united Ireland or nothing”.

And yet a few weeks after Bloody Sunday two old drunken sailors sat in 10 Downing Street, downing whiskey into the early hours, clinking glasses and singing their hearts out. Gerry even played his harmonica and sang ‘Danny Boy’ (the ‘Derry Air’). There was no talk of the Falls Curfew, the Ballymurphy Eleven or Bloody Sunday.

Yes, Gerry Fitt and Ted Heath had a whale of a time.

In 1985 Ted Heath bought Arundell, his splendid house in Salisbury’s Cathedral Close. His express wish was that after his death the house would be turned into a museum. He was so popular that sixteen of his near neighbours objected and originally the council supported them but the trustees got their way and the house was opened to the public in 2008.

As a passionate teenager, incensed by the curfew, internment and the killings on Bloody Sunday, I remember writing in my diary thoughts of assassinating Heath and his Home Secretary Reginald Maudling.

That was in 1972.

A few weeks ago I was in the Salisbury neighbourhood for the wedding of my niece. And now I stood in front of the gates of Ted Heath’s long driveway and smirked with satisfaction.

A few weeks ago I was in the Salisbury neighbourhood for the wedding of my niece. And now I stood in front of the gates of Ted Heath’s long driveway and smirked with satisfaction.

The large queues of fans snaking around Cathedral Close had never materialised. It hadn’t enough visitors, wasn’t viable, had to be closed and was to be put up for sale. But they had forgotten to take the sign down, asking for £8 per visitor on any Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday or Saturday afternoon!

Back in 1972 we had no idea that our MP, the leader of the SDLP, was partying with the man responsible for killing his constituents, but in retrospect you can now see that it was all in character for Fitt and what came next, his support for Thatcher during the H-Block hunger strikes, and his elevation to the House of Lords after the people of West Belfast voted him out.

Both men died within weeks of each other: Heath in July and Fitt in August 2005.

EPILOGUE

From the BBC, 11th August, 1971:

“Looking jubilant as he stepped on to dry land, Mr Heath told waiting reporters, ‘I am absolutely delighted we won. It has been a team effort throughout.’

“Looking jubilant as he stepped on to dry land, Mr Heath told waiting reporters, ‘I am absolutely delighted we won. It has been a team effort throughout.’

“At a news conference shortly after his arrival at Plymouth, Mr Heath refused to discuss Northern Ireland, saying only that he had been kept closely informed of events by radio link.

“It was left to his press officer, Henry James, to explain that all decisions on the government’s course of action had been taken before Mr Heath sailed. He said the prime minister went on board the Morning Cloud as planned to avoid raising the alarm that something unusual was afoot.

“There were contingency plans in place to lift Mr Heath off the yacht by helicopter, but if that had happened, the Morning Cloud would have been disqualified and Britain’s chances of winning the Admiral’s Cup would have virtually disappeared.”

You couldn’t make it up, could you?