A North Vietnamese spy, ‘the Captain’, who infiltrates the South’s military and security establishment, is so singularly dedicated to his role that he even ‘flees’ Saigon with his General, government officials and senior military figures, so that he can continue to spy for his communist comrades on the immigrant community which settles in California, after the humiliating US withdrawal in April 1975.

“I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds,” he says, in the opening pages of this brilliant novel as he begins writing down his confession while under arrest and in solitary confinement.

His account of his activities and his two ‘schizophrenic’ lives, viewed from diametrically opposite angles, are about the brutality of an unnecessary and unjustified conflict and the ramifications of the decisions an individual involved in conflict makes.

His account of his activities and his two ‘schizophrenic’ lives, viewed from diametrically opposite angles, are about the brutality of an unnecessary and unjustified conflict and the ramifications of the decisions an individual involved in conflict makes.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, was four when his family fled Vietnam for the US as the North Vietnamese Army and their National Liberation Front allies in the South took power.

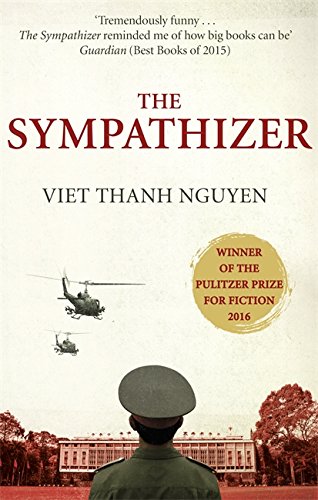

Nguyen is now an award-winning writer and his writing is quite powerful. This, his debut novel, written when he was forty four, won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

It is an astonishing novel from the quality of prose, in terms of style and plot, and subject matter – the story/confession of an articulate and cultured communist spy told with irony, humour and pathos. The central protagonist, while immoral, is not as ruthless or heartless as the ex-Nazi mass murderer, the sophisticated and urbane Maximilian Aue, the narrator of that stomach-churning novel The Kindly Ones.

Nguyen also wrote Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, described as “a powerful reflection on how we choose to remember and forget”.

In that book he states: “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”

Without spoiling what otherwise is a tour de force, I have to say that the one thing I found unsatisfactory in The Sympathizer was the ending. Be that as it may it is an incredible first novel with many excursions into the nature of violence and the subject of conscience.

The unnamed narrator, the illegitimate son of a French Catholic priest and a teenage Vietnamese villager, who suffered opprobrium because of his status, but who had risen to become a powerful police Captain, looks around at the young soldiers defending the lost cause of the South, ‘a basket case kept alive only through the intravenous drip of American aid’, and finds himself in sympathy with them: “I confess that I felt for them all, lost in their sense that within days they would be dead, or wounded, or imprisoned, or humiliated, or abandoned, or forgotten.”

In California the vanquished Vietnamese immigrant community (an emabarrassing reminder of defeat) have been reduced to the status of outcasts, accepting menial jobs, regardless of individuals’ former qualifications and eminence. Some former military plan and imagine a counter-revolution and begin training and sending men back into Laos. All the while, the Captain sends this information back to Man, his comrade and intelligence chief in Ho Chi Minh City, who had also been a spy in the Saigon police.

Man had been the person whose emollient reassurances the Captain relied on, during the American war, when he raised his moral misgivings about certain of their actions. On one occasion, after handing over the assault plans of a Ranger battalion, he says, “Innocent men would die as a result of my actions, wouldn’t they? Of course men will die, Man said, masking his words behind his folded hands as we knelt in a pew. But they aren’t innocent. Neither are we, my friend. We’re revolutionaries, and revolutionaries can never be innocent. We know too much and have done too much.”

In California, the Captain finds himself in an invidious situation when the General suspects that they have a spy in their midst. The Captain deliberately casts suspicion on another émigré, a former major, only to find himself ironically now tasked to carry out the execution along with Bon, who lost his wife and infant to incoming mortar fire as their plane taxied on the runway in Saigon, and who just wants to return to Vietnam to resume the war against the communists.

“I said, What if he’s not a spy? We’ll be killing the wrong man. Then it would be murder. Bon sipped his beer. First, he said, the General knows stuff we don’t. Second, we’re not killing. This is an assassination. Your guys did this all the time. Third, this is war. Innocent people get killed. It’s only murder if you know they’re innocent. Even so, that’s a tragedy, not a crime.”

The Captain, while an efficient spy, who’d been present at CIA assassinations and the torturing of prisoners, is not, however, ‘a gunman’, as he admits.

“In our country, killing a man – or a woman, or a child – was as easy as turning a page of the morning paper. One only needed an excuse and an instrument, and too many of all sides possessed both. What I did not have was the desire or the various uniforms of justification a man dons as camouflage – the need to defend God, country, honor, ideology, or comrades – even if, in the last instance, all he really is protecting is that most tender part of himself, the hidden, wrinkled purse carried by every man. These off-the rack- excuses fit some people well, but not me.”

In another incident – the proposed killing of a journalist in Los Angeles with alleged ‘VC’ sympathises – is discussed in terms of what the CIA typically instructed them to do during the war:

“Here’s the shopping list. Go and bag some. So we’d go into the villages at night with the shopping list. VC terrorist, VC sympathizer, VC collaborator, maybe VC, probably VC, this one’s got VC in her belly. This one’s thinking of being a VC. This one everybody thinks is VC. This one’s father or mother is VC, therefore is VC in training.”

After the killing he is often haunted by the major whose severed head even shows up at a wedding banquet! Despite the grim story the ironies of situations in which the Captain finds himself can be very funny – particularly when he becomes an advisor on the making in the Philippines of a movie about the war.

Interviewed in 2015 about the book Viet Thanh Nguyen said:

“I see the Vietnam War not as a discrete incident, a chapter to be closed, but as part of a continuum of American war since the 19th century that has sought to expand the borders and powers of the United States. Other interventions or invasions can be compared to the Vietnam War, and the narrator’s situation can be transposed elsewhere, because what we are really dealing with is what the novelist Gina Apostol calls a psychological disorder (speaking of the military industrial complex) — that is central to American culture and character. The Vietnam War just illustrates that and stands out because American ambitions failed.”