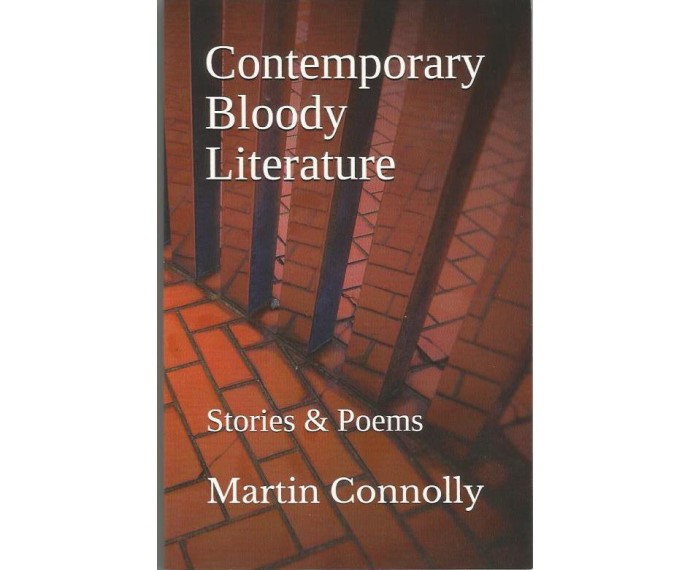

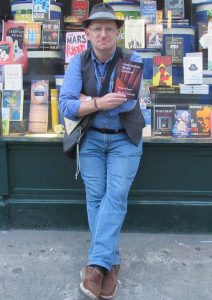

I loved this little book of stories and poems which the author, Martin Connolly, autographed for me at Scribes at the Rock in August 2018 shortly after it was published by Snowchild Press. Martin (from Belfast) is Professor of English Literature at Tsurumi University, Yokohama, and has lived in Japan for over twenty five years, but has lost none of his native irony or mischievousness, which is evident throughout this work.

The cruelty of human nature is depicted brilliantly in Cape Cod, when a couple who were once lovers at university in Dublin, Michael and now US-domiciled Sarah, but who have long since gone their separate ways and married, meet up again at the invitation of Sarah and her husband to stay with them for five days. So powerful is the writing that we experience total unease as the story unfolds with Michael and his two young sons being humiliated and abandoned.

In The Interview an unemployed claimant sits down before a bureaucrat only to discover that he is inadvertently ‘dead’. Of course, when that is cleared up and the form completed the claimant then has to take another seat for another interview in another tedious process and tussle with officialdom in an experience many can identify with. What transpires, however, is something Borgesian – about entrapment and alienation.

Many of the poems are beautiful and wonderful – little observations about nature; a tribute to a dead friend – or hilarious doggerel filed under Middle Age Nonsense.

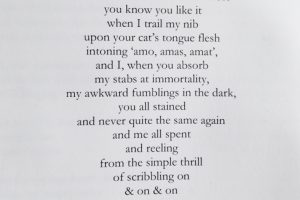

In per pagina ad lux aeterna et amor the poet speaks about the sensual experience of returning like a lover to the body of the page after an absence of some duration:

Similarly, that old analogue thing called love is a melancholic paean to the LP (the Long Playing record), how tactile it was to lift it out of its artistic sleeve, and observe those mysterious grooves within which, for example, a jazz orchestra, a great band or songs lurked, place it on the turntable, drop down the needle until friction gave way to frisson. I had déjà vu and a little feeling of regret reading this poem – ‘we’re all smart and digital now’ and ‘who cares now/for all those liner notes and stuff’.

The poet knows we cannot turn back time or block ‘progress’ where everything is at our beck and call and gratification is instantaneous, but still, ‘has something gone perhaps?’ the way video killed the radio ‘star’, or, as Queen put it about an earlier age of fulfilment, in the wistful Radio Gaga, ‘everything I had to know/I heard it on my radio.’

The book takes its title from the eponymous story, Contemporary Bloody Literature, about a retiring Californian Emeritus Professor, John Gallagher, who in his final speech before a gathered crowd of academics, students, literary critics and publishers, departs from his subject and decides to put the boot into the latter two whom he holds in particular contempt and responsible for the dumbing down of literature and the manipulation of culture. He felt he was striking a blow ‘for the honest reader of good books.’

During the Q&A, to support his case about the mediocrity of modern literature, Gallagher displays slides of book covers and ridicules familiar authors:

‘Exhibit A, ladies and gentlemen: Days Without End, by Irish writer Sebastian Barry. Winner of the Costa Book of the Year Award 2017, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, no less. An exercise in ventriloquy that wouldn’t fool a child: a middle-class Dublin writer narrating as a mid-19th century uneducated American soldier; oh the grammar he abuses! But… it ticks all the boxes!’

He then goes on to excoriate Dead Man’s Walk by Larry McMurtry; Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy; and Lord of the Flies by William Golding; and the authors JM Coetzee and Kazuo Ishiguro. But just before his host intervenes and puts an end to the unprecedented exercise in iconoclasm Gallagher gets in one more knife: ‘And I haven’t even time to mention the bastard post-Modernist brigade: a bunch of piss-poor amateurs entertaining so-called intellectuals with nonsense… You damn people have a lot to answer for!’’

He thinks to himself that once a writer or poet becomes a ‘National Treasure’ all discussion goes out the window, and he recalls another famous poet telling him: ‘Heaney was as untouchable as Israel.’

However, in a subsequent encounter with an aspiring young writer, shortly after this lecture, we witness another side to Gallagher, his contempt and pomposity, when he worries that his words, his manifesto, might do even worse collateral damage and ‘been a call for the self-publishing brigade’, those lumpen inferiors whom he also clearly loathes.

But I’ll not disclose how this very satisfying short story ends in a full stop!