In this personal piece Ciarán Quinn, Sinn Féin Representative for North America, responding to reports of British Government plans to produce an ‘official’ history of the conflict, explains the importance of remembering all that happened in the past and that no ‘one truth out-trumps another’.

‘why some people be mad at me sometimes’

by Lucille Clifton

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine

It was a job most of us will be called to do. My father had died a couple of years ago, my mother wanted us to clear out the attic. It was full of things that once were thought useful, put away for another day. Family mementoes, pieces of the jigsaw of lives lived.

Among the school reports, outdated passports, and dulled glasses was a plastic bag of newspapers. The papers, long browned, and neatly folded, included Irish News death notices and photos in the Andytown News of nights out.

They were mostly from the 1980s, but in the middle of the bundle were pages from the Irish Times and Andersonstown News from Saturday, 14 June 1975. What was so important about these dates and why had they had been kept?

The Irish Times pages reported on the awarding of honors to the RUC Chief Constable, a senior judge, and the governor of Long Kesh.

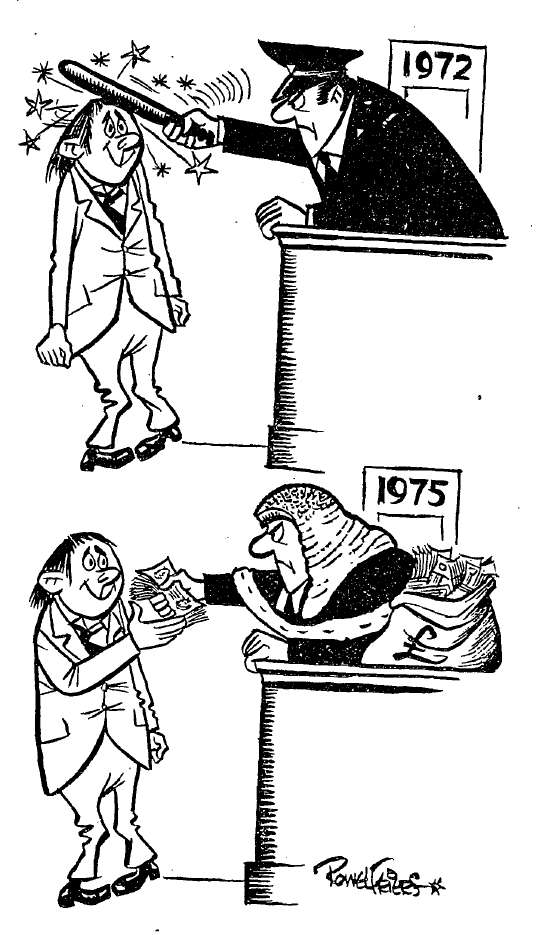

In contrast, a story on the same page detailed the rising cost of claims for compensation from injuries at the hands of the RUC and the British Army. It was accompanied by a cartoon character getting hit over the head with a baton and then given a wad of banknotes.

The cartoon, to say the least, was incongruent with the brutality of the report. To outline the issue of compensation the journalist, Conor O’Clery, followed the case of two brothers John and Jimmy, who were arrested in October 1971 for possession of arms.

Once arrested, they were first brought to Andersonstown RUC Barracks and later transferred to Springfield Road Barracks. They were in the custody of the RUC for several days, before being brought to court.

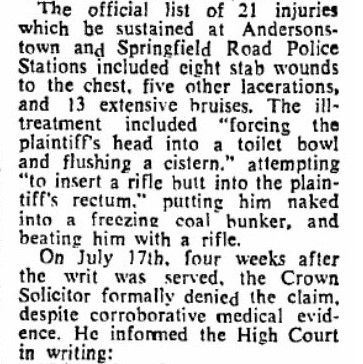

The compensation relied on an official medical report of injuries received while under arrest.

One of the brothers’ medical reports details eight stab wounds to the chest, five other lacerations, and thirteen extensive bruises. These injuries were consistent with the man’s claim that he was beaten with batons and forced on the floor of a Saracen armoured car where a boot was placed on his face and cigarettes stamped out on him.

At Andersonstown Barracks he had been stripped naked and then blindfolded. Attempts were made to administer electric shocks and insert a rifle into his anus. He was dumped naked in a freezing coal bunker where he was left for hours.

At Springfield Road Barracks the beatings continued. His head was placed into a toilet and the cistern flushed, in an early version of waterboarding. A pistol was placed in his mouth and the trigger pulled.

The torture only ended when the brothers were brought before the court and remanded to Crumlin Road Prison. The Andersonstown News carried a similar report.

In June 1974 a writ was moved for compensation for injuries received while under arrest.

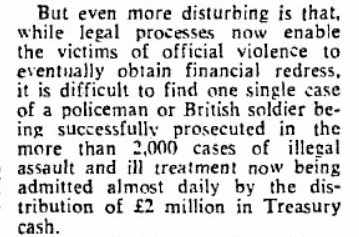

The State contested but, of course, given the overwhelming medical evidence, settled just before going into an open court.

The victims of this torture were my father, John Quinn (then aged, 26), and his younger brother Jimmy (19).

Despite the compensation and the indisputable medical evidence no RUC member was ever charged. No investigation was ever undertaken. No one in the RUC seems to have seen or heard the naked and bleeding prisoners.

My father was well aware that the law did not apply to the RUC. They were the law. It had been beaten into him.

The newspapers’ clippings were kept safe but never shown.

In the absolute moral certainty of some in unionism, my father, who was an IRA Volunteer, was the perpetrator and will never be described as a victim of torture despite the evidence. Some reading this will revert to the old ‘deserved everything he got’ or ‘what else did he expect?’ mantras.

But where do the actions of those in the RUC who tortured defenseless men in their custody fit with this absolute moral certainty? What use is a moral compass that fails to recognize victims of torture as victims and exults torturers as blameless?

The torture of my father and his brother took place fifty years ago but is still relevant to the debates of today.

He died in 2017, taking his memories to his grave. He never spoke about his experience—but kept the newspaper clippings. I’m told the scars of torture victims never really heal.

It’s not my place to forgive. That was his prerogative and he is dead.

Neither is it in the gift of the British Government to absolve those involved in the conflict or attempt to write the experiences of many like my father out of history.

No one can be forced to forget. The process of acceptance and acknowledgment cannot take place against a backdrop of denial and cover-up.

The ability to rebalance our understanding of history is both possible and necessary if we as a society are to heal.

That is why the British Government’s proposals to close investigations and impose a narrative on the past (its proposals to nominate historians to write an ‘official’ history of the conflict) are so insidious. Continuing a convenient lie at the cost of an inconvenient truth.

The official narrative held for years. The truth was hidden in plain sight for those who wanted to look.

On the same day, on the same page, that the Irish Times carried the story about the torture of my father, they reported on the Queen’s Honors. Pictured was the RUC Chief Constable who was awarded a Knighthood.

I am proud of the resistance and sacrifice of my father’s generation. But that pride also carries a weight. I am not blind to the hurt inflicted by republicans. I have had the privilege to meet with victims of republican violence. Every encounter leaves a mark.

The same must hold for others. We cannot only remember the bits of history we like. If you commemorate the RUC or the British Army it cannot be at the cost of denying the experiences of others.

If we are to remember, let us remember it all. No one truth out-trumps another.

The words of American poet Lucille Clifton are as relevant to dealing with our past in Ireland as they are with the US coming to terms with its past.

The British Government tells us to accept their memories while they simultaneously deny mine.

The conflict is over. For that, we can all be thankful. The various Agreements negotiated assert the primacy of politics, democracy, and peace.

Our history was brutal. For the sake of the future, we must remember, some may forgive, but we cannot forget.