This is my long review of Partition – How and Why Ireland was Divided by Ivan Gibbons which appeared in the Irish Examiner, May 1, 2021.

ITS one hundredth birthday falls on May 3, yet no unionist or revisionist historian has ever written a book titled, The Success of Partition. Doubts over its future are now part of mainstream and popular discourse. A democratic and peaceful way forward was established in the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) in 1998, including the mechanism of a referendum for bringing about constitutional change.

Yet, today there emerges the unseemly sight of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael leaders placing obstacles in the way of unity. This is how the former Irish ambassador to Canada, Ray Bassett, who was intimately involved in the Good Friday negotiations, recently described this stance:

“People in power in the south have sniffed the air and realise that a new united Ireland with seven million (five million in the south and two million in the north) could be an existential threat to their position of dominance… Without a blush of shame, both these parties have jettisoned one of the main provisions of the GFA in the glorious pursuit of self-interest.”

He was referring to the proposed tinkering that is going on around the issue of consent, which would introduce a new unionist veto. Some have even suggested that until unionists sign up to a united Ireland there shouldn’t even be a referendum, or that until there is a majority among unionists in favour of change unity must wait. In other words, a majority if it is unionist can maintain the union, regardless of what nationalists think; but a majority, if it is nationalist, can’t change the union without the permission of the unionists. We have paid a heavy price for pandering to that intransigence, and it would be wrong today for FF/FG to make the same mistake.

As Bassett puts it: ‘It would be far better for those seeking to avoid a referendum to be honest and openly declare that they favour partition.’

Partition by Ivan Gibbons is one of a number of timely books released this year. While it does cover the post-partition Boundary Commission debacle, it does not, however, go into in any detail about the consequences of partition. For that you would need to consult the likes of The Orange State by Michael Farrell (1976), which comprehensively deals with “the nationalist nightmare”—to quote the late Peter Barry, former Cork TD and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

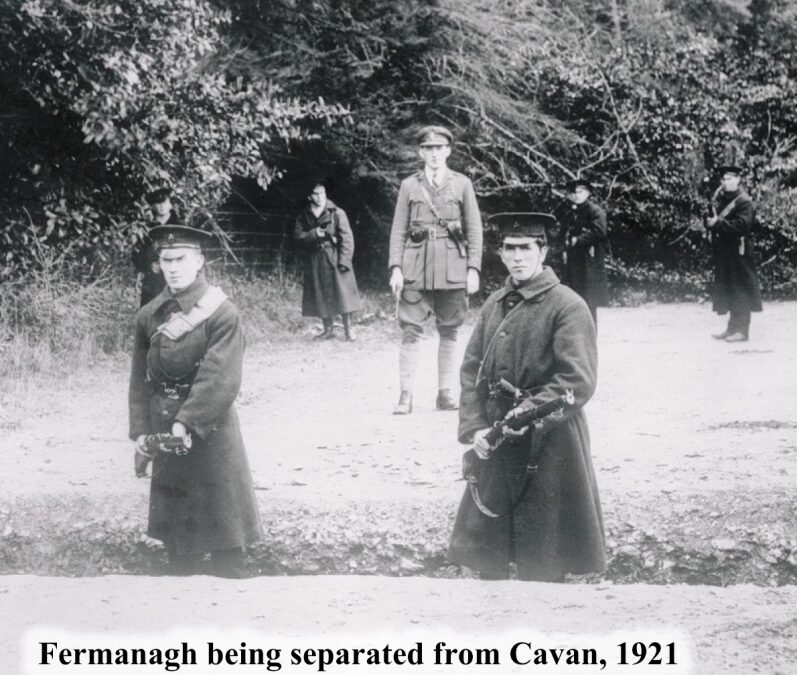

That nightmare, for thousands of abandoned nationalists, began when the state of Northern Ireland was created as a separate legal entity on May 3, 1921, under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The IRA, including its Northern Divisions, was still fighting for complete Irish independence and an end to British rule – the truce would be announced a few weeks later, on 11 July – but partition was presented as a fail accompli before republicans even crossed the threshold of 10 Downing Street.

The northern parliament was first based at Belfast City Hall, until Stormont opened in 1932. It has six pillars at its entrance and six floors to represent the Six Counties, which include Tyrone and Fermanagh whose nationalist majorities had good grounds for believing they would not be included, even on a temporary basis. That was until the incompetent or incredibly naïve John Redmond betrayed them and agreed to their inclusion, along with Derry, Antrim, Down and Armagh. That fatal decision fractured the integrity of Ireland as a political unit. His other decision, to send the National Volunteers to their deaths in the trenches of WWI, believing that would ingratiate himself to Britain, demonstrated his failure to understand imperialism and colonialism.

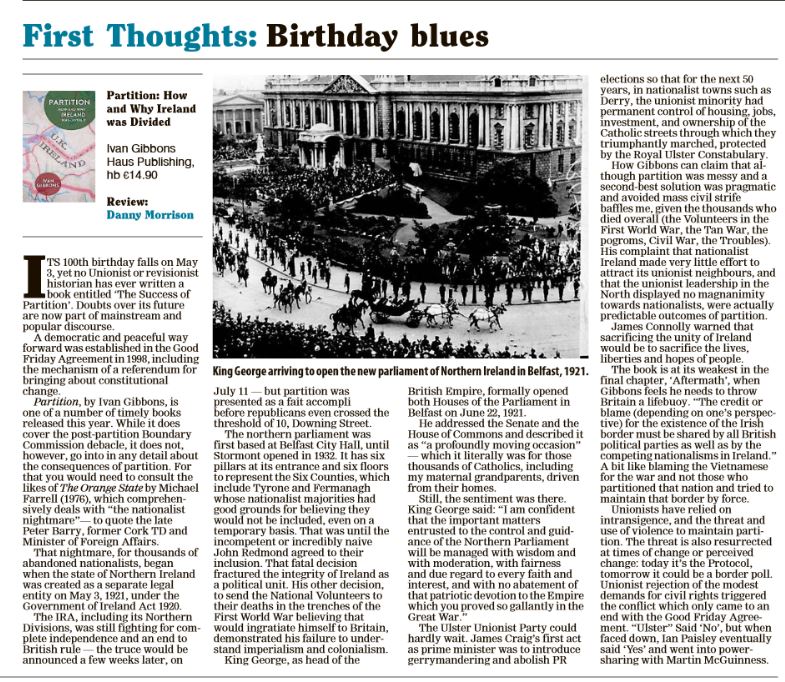

King George, as head of the British Empire, formally opened both Houses of the Parliament in Belfast on June 22, 1921. He addressed the Senate and the House of Commons and described it as “a profoundly moving occasion”—which it literally was for those thousands of Catholics, including my maternal grandparents, driven from their homes.

Still, the sentiment was there. King George said: “I inaugurate it with deep-felt hope, and I feel assured that you will do your utmost to make it an instrument of happiness and good government for all parts of the community which you represent… I am confident that the important matters entrusted to the control and guidance of the Northern Parliament will be managed with wisdom and with moderation, with fairness and due regard to every faith and interest, and with no abatement of that patriotic devotion to the Empire which you proved so gallantly in the Great War.”

The Ulster Unionist Party could hardly wait. James Craig’s first act as Prime Minister was to introduce gerrymandering and abolish PR elections so that for the next fifty years in nationalist towns like Derry the unionist minority had permanent control of housing, jobs, investment, and ownership of the Catholic streets through which they triumphantly marched, protected by the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

How Gibbons can claim that although partition was messy, and as a second-best solution was pragmatic and avoided mass civil strife baffles me, given the thousands who died overall (the Volunteers in WWI, the Tan War, the pogroms, Civil War, the Troubles). His complaint that nationalist Ireland (by which he means the confessional South) made very little effort to attract its unionist neighbours, and that the unionist leadership in the North displayed no magnanimity towards nationalists, were actually predictable outcomes of partition. James Connolly warned that sacrificing the unity of Ireland would be to sacrifice the lives, liberties and hopes of people. As early as 1914 he condemned the great betrayal by Redmond and his Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), and clearly stated that it would lead to “a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish Labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.”

Gibbons’ contends that abstaining from the Westminster debates on partition, first by the IPP in January 1918, and after December by Sinn Féin, was a major mistake, as if the presence of either would have made a whit of difference. The leader of the Conservative Party and future British Prime Minister, Andrew Bonar Law, had supported illegality and armed rebellion, and made it clear where the issue would be decided when he said, “There are things stronger than parliamentary majorities . . . I can imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster will go which I shall not be ready to support.”

Establishing Dáil Éireann was important symbolically and practically – as well as formalising the authority of the IRA – in challenging the British claim of sovereignty and via alternative power structures.

The book is at its weakest in the final chapter, Aftermath, when Gibbons feels he needs to throw Britain a lifebuoy. “The credit or blame (depending on one’s perspective) for the existence of the Irish border must be shared by all British political parties as well as by the competing nationalisms in Ireland.”

A bit like blaming the Vietnamese for the war and not those who partitioned that nation and tried to maintain that border by force.

Unionists have relied on intransigence, and the threat and use of violence to maintain partition. The threat is also resurrected at times of change or perceived change: today it’s the Protocol, tomorrow it could be a border poll. Unionist rejection of the modest demands for civil rights triggered the conflict which only came to an end with the Good Friday Agreement. “Ulster” Said No, but when faced down Ian Paisley eventually said Yes and went into power-sharing with Martin McGuinness.

PARTITION – How and Why Ireland was Divided by By Ivan Gibbons, Haus Publishing, H/B 172 pp, £12.99