I was on a panel on Sunday with Alex Kane and Eamonn Phoenix. We were on Radio Ulster’s Sunday Sequence, chaired by Audrey Carville, and were there to discuss the recently released state papers from London, Dublin and Belfast covering the period before and after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement on 15th November, 1985.

Unfortunately, due to time constraints, each of us only got the chance of answering two questions and so a lot of the subjects weren’t broached. But here are some observations from the papers.

In November 1984 at Chequers Thatcher had infamously rejected the New Ireland Forum proposals of the Dublin government/SDLP with her ‘out, out, out’ remarks. However, after that, senior civil servants and some diplomats on either side got down to work, discretely, with the British Foreign Office being the most (relatively) sympathetic to Dublin’s needs. Garret Fitzgerald said that Thatcher’s rejection had “left the SDLP in a state of shock” and claimed that her words had been “the biggest boost to the IRA he could ever remember.”

In November 1984 at Chequers Thatcher had infamously rejected the New Ireland Forum proposals of the Dublin government/SDLP with her ‘out, out, out’ remarks. However, after that, senior civil servants and some diplomats on either side got down to work, discretely, with the British Foreign Office being the most (relatively) sympathetic to Dublin’s needs. Garret Fitzgerald said that Thatcher’s rejection had “left the SDLP in a state of shock” and claimed that her words had been “the biggest boost to the IRA he could ever remember.”

The talks were in private, in confidence, and the exploratory papers were not initially circulated within the NIO because the British anticipated its fury.

Throughout the Troubles the NIO wielded a disproportionate and malign influence on British decision-making (which can be seen at the time of the hunger strike). Even under Direct Rule, unionists, for all their complaining, had their fellowmen in senior positions within the NIO and civil servants who regularly leaked to them.

In return for the South being consulted about the North the British wanted increased cross-border security cooperation, wanted Dublin to sign up to the European extradition treaty and to amend the moot territorial claim of Articles 2 & 3 of the Irish constitution.

Interestingly, Britain was already receiving top intelligence from the Southern security forces, despite Dublin being accused of holding back and of using security as a bargaining chip.

In one paper Britain’s security coordinator says that Special Branch and MI5 had “excellent relations” with Garda Intelligence and Security Branch, and “benefit from a degree of co-operation and from a flow of intelligence which we believe to be at a greater level than is suspected by at least some Irish ministers.”

The other reality was, of course, that the South was paying more per capita towards cross-border security costs than was the British exchequer.

Thatcher continually complains about ‘the Irish’ wanting to interfere in Britain’s internal affairs, then, in despair at the seemingly intractable nature of the conflict, she fleetingly considers whether a possible answer “might not simply be a redrawing of boundaries”, that is, repartition, and handing some parts of the North to the South! Of course, she isn’t the only one disconnected.

The stance of the Southern government is pathetic. Fitzgerald begs that all they want are ‘minimal steps to protect the minority’ and that the SDLP must be saved from the electoral rise of Sinn Féin. He suggests that the authorities should knock down Divis Flats, because conditions there only breed support for Sinn Féin and the IRA, without seemingly realising that Sinn Féin and its supporters were for years involved in the Demolish Divis Campaign! (Interestingly, in another telling remark, Cardinal Ó Fiach informs the Irish ambassador to the USA who is in the North on a fact-finding tour, that “in the Belfast area alone the Housing Executive were receiving approximately 140 enquiries a week from Sinn Féin to four from the SDLP.”

Perhaps the most embarrassing statement is that from Foreign Affairs Minister Peter Barry who basically asks Englishman Douglas Hurd if he, Barry, could go for a drink on the Falls Road. Barry suggests that ‘the most difficult nut to crack’ was West Belfast. “It would be a good thing for an Irish minister like himself to be seen having a drink in a local club to demonstrate things had changed.”

Douglas Hurd disagreed strongly.

The Agreement was vehemently opposed by unionists who picketed and violently attacked the Maryfield Secretariat, where Irish civil servants were based. Unionists resigned their Westminster seats and forced by-elections in January 1986 to show that ‘Ulster Says No’ to the Agreement. They held a Day of Action in March 1986 during which there was widespread intimidation of people attempting to go to work. The RUC failed to intervene and in one incident an RUC Landover was actually driven out of the way to allow a tractor and trailer to block the road to the Stormont estate. Not that this ‘solidarity’ ingratiated the police with loyalists: loyalists set about petrol-bombing or opening fire on RUC officers’ homes. Over 500 homes were attacked in 1986 and 120 families needed rehousing.

One government paper says of Peter Robinson’s position on the attacks; “He found it impossible to condemn them. ‘Loyalist violence against the RUC was inevitable. Everybody must regret the turn of events, but the British Government looks on the RUC as being the instrument for imposing the Anglo-Eire Agreement,’” said Robinson. Another file recounts how, at the dissolution of the Assembly in June 1986, eighteen DUP members and the UUP’s Jeffrey Donaldson and Frazer Agnew had refused to leave the chamber until, at the request of the Assembly clerk, the RUC “moved in to eject them” at 2am. Paisley and Robinson were the last to be carried out, with Paisley infamously telling the RUC men “not to come crying to me if your houses are burned”.

In August 1986 Peter Robinson led a 150 strong group of loyalists, some carrying cudgels and dressed in paramilitary uniforms, in ‘an invasion’ of the village of Clontibret in County Monaghan. Robinson was arrested and later fined €17,500. His paying the fine led to him being derided as ‘Peter Punt’ by former DUP member George Seawright.

The hypocrisy of the British with regards to Seawright is revealed in the papers. Seawright had once said that Catholics who object to the singing of the British national anthem were “Fenian scum” who should be burned in an incinerator along with their priests. The British government refused to meet with elected representatives of Sinn Féin because of Sinn Féin’s position on the IRA’s armed struggle.

But here is how a Mr ND Ward from the Northern Ireland Office squared that it was right to meet Seawright but not a member of Sinn Féin!

“Mr Seawright is a maverick and, some would say, a nutcase, but he is not a subversive in the Sinn Féin sense and to treat him on a par with Sinn Féin and refuse to see him as part of a delegation might only seem to enhance his standing in some quarters.”

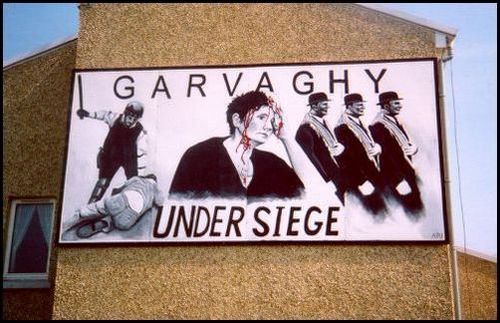

Despite Dublin allegedly having a consultative role in the North its influence could not protect the nationalist community along the Garvaghy Road in Portadown. On 12th July 1986 the RUC forced an Orange Order march through the nationalist area, batoning protestors off the streets, and sparking several days of rioting. Ultimately, it was the steadfastness and resistance of the people there which stopped that sectarian coat-trailing exercise and there has been no march on the Garvaghy Road since 1998.