Ciaran Quinn is the Sinn Féin Representative to North America. Here he reviews Northern Protestants on Shifting Ground by Susan McKay.

-oo0oo-

Susan McKay’s book is a master class in the art of listening and a damning indictment of the failure of dialogue.*

The book consists of a series of interviews with Protestants as the author arcs her way around the north of Ireland. The interviewees present a wide variety of opinions, experiences, and identities. All are given the space to articulate their views and experiences.

It is this approach that sets the book apart: there is no attempt to judge or interpret. While the author provides context and background, the challenge is for the reader to listen.

In a book that could well have been a dry academic exercise, in the hands of Susan McKay the interviews at times sparkle with life and hope and in others with unbearable pain, loss, and uncertainty.

As an Irish republican it can be a challenging read to be confronted with the pain inflicted by republicans. This is a difficult but necessary experience to remind us all of the cost of conflict. For many, it is the prism through which they view modern Irish republicanism.

While there are good and progressive initiatives, the failure of community dialogue runs through the book. A failure to acknowledge and listen to the other.

The legacy and pain of the conflict are alive in families bereaved by republicans who now see republicans in the ascendency. But this is not a shared pain. Very few in the book recognize the hurt and pain caused by the state on the nationalist community. Again a failure of dialogue.

Part of this can be led at the door of republicans. What we say and what people hear can be two different things. Growing up in West Belfast, where Protestants were more of a mythical or idealogue construct, ‘Brits Out’ meant the British Army on our streets. For many Protestants, they took this to mean they had no place on this island that they call home. The complete opposite of Irish republican values.

Dialogue requires partners. Protestant and unionist refusal to engage in dialogue, to view everything as a zero-sum game runs, through the book. ‘We are the people’, ‘What we have we hold’, ‘No Surrender’, are the touchstones for some. Slogans of exclusion and inequality. Fixed in a time long gone, with no space to contemplate the future.

Tom Paulin summed it up in his poem Desertmartin:

It’s a limed nest, this place.

I see a plain Presbyterian grace sour, then harden

Those Protestants who differed, who stood outside the political unionist world view, were branded a Lundy.

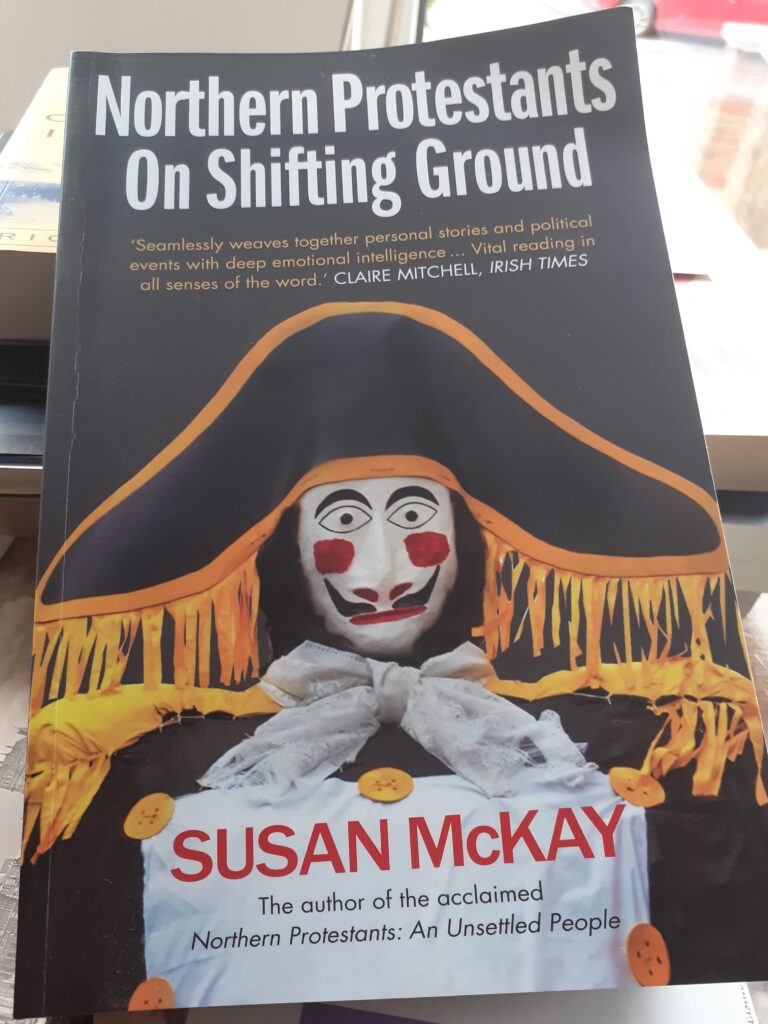

Robert Lundy was Governor of Derry during the siege of 1687 who sought terms for the surrender of the city to the Jacobin forces. He was forced to flee the city. Every year the Protestant Apprentice Boys burn an effigy of the traitor Lundy. This effigy is the face on the book cover.

The fear of being called a Lundy has permeated the Protestant identity. To engage with a progressive discussion, to acknowledge the loss and suffering of others, and to look to the future, runs the risk of being a Lundy and ostracized from your community. The interviews reflect those ostracized, those who fear being called a Lundy, and those who know the power of that allegation.

This approach of outing Lundies and cries of ‘No surrender’, sustained and maintained the northern state for decades. The rhetoric made real with pogroms, discrimination, and repression.

Derry is no longer a Protestant city. It is a majority nationalist city. It is a shared city, with an agreement which sees the Apprentice Boys parade and march through the city to burn Lundy. The old certainties are gone. The north is no longer a Protestant state for a Protestant people. That is a central theme that runs through the book.

I was surprised by the power the Protestant churches hold over many of those interviewed. Some of the most powerful testimonies are from members of the LGBTQI community who have been rejected by a church they love. In one interview, an aunt addresses the homosexuality of her nephew with a heart-warming Christian response.

The restrictive, conservative, fundamental Protestantism is being challenged by a new generation that is struggling to find a home. They are pro-equality, in favour of abortion rights, and looking to build a more progressive society. They have no fear of the south or constitutional change.

They support the union with Britain but are democrats and are prepared to accept the democratic outworking of a unity referendum. They also want to know what their place in a united Ireland will look like.

Interestingly some put this challenge to republicans but fail to say, themselves, how they will make the north a welcoming home for Irish citizens. I was once asked by a member of the Ulster Unionist Party, the party that operated a single party state for fifty years from partition until just after Bloody Sunday, ‘Why won’t republicans make Northern Ireland work?’

An irony lost in history.

Brexit looms large in the book with consistent criticism of the Democratic Unionist Party in many of the interviews. The criticism of the DUP since the book has been published is now validated through falling opinion polling. It is the qualitative complement to quantitative polls.

One interviewee was brutal in their honesty. They voted for Brexit because they were told it would build a ‘border as high as you can get it and all foreigners out. And no united Ireland.’ The DUP sold Brexit as strengthening the Union.

Instead, they got Boris Johnston and a regulatory border down the Irish Sea.

This has not led to massive civic unrest. There is no evident support, apart from a vocal few, but more a resigned acceptance that ‘Britain doesn’t care and the South doesn’t want us.’

This is also a hopeful book. Identities are not fixed or permanent. They change over time and with circumstance. Dialogue can and must be built. Healing or acknowledgment of the past is possible. The rejection of violence and the primacy of democracy is a constant in all but a few contributions.

The author prints all the messy contradictions of a society born of conflict. If we can listen without judgment, engage without conflict, we can build a dialogue of equals.

It is past time for the Protestant community to shake of the ghost of Lundy and look to the future. To stop being in the words of Peter Robison, ‘Border Poll Deniers’. For some that will be to build the case for continued partition. For others to define their place in a united Ireland. And for all to accept the primacy of peace and respect for the democratic vote of the people. These changes can only come from within that community.

I hope this book is part of that process.

For Irish republicans, it can be a challenging read. Our words matter. We may disagree with the interviewees but we cannot deny their experiences or dismiss their opinions if we are interested in building a new and united Ireland that is a home for all.

The skill of Susan McKay is evident as she poses these questions through an engaging, informative, and thought-provoking book.

*Northern Protestants – On Shifting Ground by Susan McKay, Blackstaff Press. Paperback £14.52, Kindle £7.19. And Amazon.