Found two gems in the Oxfam shop in Belfast’s Ann Street, which I’ve read before, but I bought them anyway to give to friends. John Banville’s The Book of Evidence is probably his best, in my opinion, based on a real life crime in Dublin in 1982. But the other book is astonishing – a novel based on a real life prison experience from 1971 until 1991.

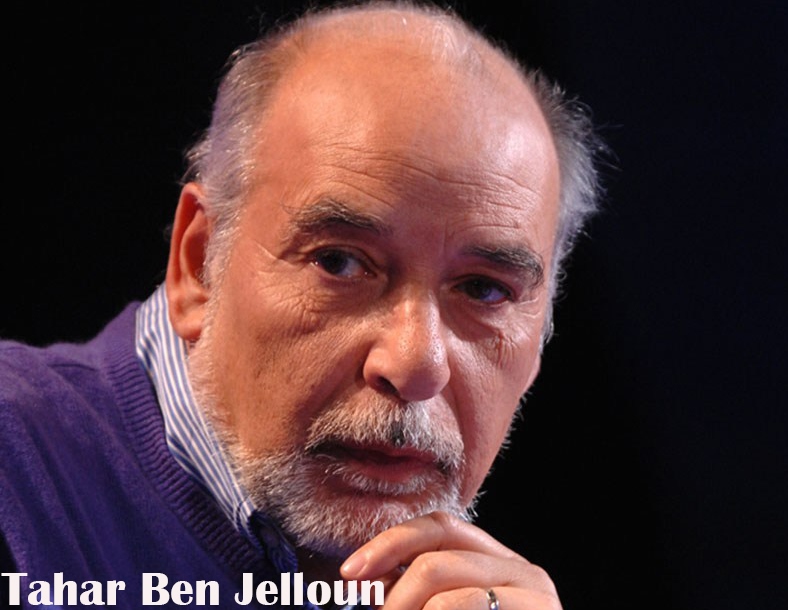

I reviewed The Silence of Absence, the Blinding Absence of Light by Tahar Ben Jelloun for a newspaper or magazine in 2005, and the review appears on my old website which is not really compatible with the platforms the majority of people use today to access the net. So, here is the review in a more accessible format.

It was the King’s forty-second birthday and his eight-hundred guests were assembled in his summer palace. Among them were foreign ambassadors, representatives of the cream of Moroccan society and General Medbouh, head of the military household.

As they ate their lunch there was a loud burst of gunfire.

Medbouh, who had spoken out against corruption, had planned a coup, along with two confederates, one of whom Lt. Col. Abadou, head of the cadet training school, had mobilised fourteen hundred trainees. He told them that they were going on an ‘exercise’, but on the outskirts of the Moroccan capital, Rabat, he claimed that King Hassan II was in danger from subversives and that they had to surround the palace. The enemies were disguised as “guests and golfers” and the men were not to fire unless absolutely necessary.

For whatever reason the soldiers opened fire wildly and massacred close to one hundred guests, including the Belgian ambassador and the Ministers of Justice and Tourism. Medbouh was killed in confused circumstances and the coup quickly collapsed.

Within seventy-two hours the leaders, who had planned to set up a revolutionary council and depose the pro-western Hassan, were executed by firing squad. Over a thousand members of the armed forces were brought to trial. Middle-ranking officers were sentenced to lengthy prison terms, including life, and others, who had been misled, were given sentences of three or five years. It was July 1971.

Based upon the experiences of a junior officer in the coup, Aziz Binebine, the well-known North African writer, Tahar Ben Jelloun, four years ago wrote a novel, This Blinding Absence of Light which won last year’s IMPAC award in Dublin.

It is an astonishing story of human endurance and is told through the eyes of twenty-seven-year-old Salim, whose father had deserted the family years earlier to become a confidant and courtier to the King. Salim takes part in the coup, but never fires a shot, and is horrified by the carnage.

Wounded and arrested he is thrown into the back of a blood-soaked lorry where the living haven’t been sorted from the dead. He is later sentenced to ten years in jail but after two years is secretly transferred to Tazmamart (as was Binebine), a secret prison in the desert, where their diet for the next eighteen years consisted of bread and a starchy liquid. There were no doctors or medicines available.

Salim is tall and cannot walk upright in the cell which measures ten feet long, is five feet in breadth and height. Eventually his spine becomes deformed. He and his comrades are held in total darkness, apart from being in the open for a half hour or so to bury their dead, the first one of whom succumbed to insanity after forty-seven days. The next to die was Driss who had a disease of the bones and muscles. His folded knees had worn a hole in his rib cage, and the ribs had worked their way into the joints, making it impossible to unbend his limbs. He was buried as a ball-shape.

During the day the half-underground cells boil; at night they are freezing. Each cell has a vent with an indirect opening that allows in air but no light. Anyone so feeble as to drift into sleep during the cold nights froze to death within a few hours. The prisoners have no bedding – just two grey sheets, which they supplement with the clothes of the dead.

Salim realises that to survive they have to have no regrets; have to wipe out their past lives, their families, their loves. “Anyone who summoned up his past would promptly die. It was as if he had swallowed cyanide.” Later, he learns how to renounce sadness and hatred. He gives up his body to the violence of the guards but not his mind.

The prisoners shout to each other from the total darkness of their cells. Among them is Gharbi, ‘the Ustad’, who knows and recites the Koran; Karim, who became their calendar and clock and could tell the time to within a minute; Lhoucine, who is skilled with his hands and fashions a razor from the metal tip of a broomstick; Larbi who hunger strikes to death because he cannot live without a cigarette; and Wakrine an expert on scorpions.

One summer scorpions are deliberately let loose in the hole. In the darkness the prisoners have to learn how to detect and locate them because it is when they fall that they sting. Lhoucine drifted off to sleep and was stung and became delirious with a raging fear. He only survived because the guards relented and allowed Wakrine to suck out the venom. During night time another prisoner, Mustapha, is stung and is screaming: “I want to die, but not like this…”

When the guards come on duty they let Wakrine into the cell but it is too late. Wakrine staggers back in revulsion. “All the scorpions in the dungeon were on Mustapha’s decomposing body.”

Bourras dies haemorrhaging when he tries to relieve his constipation by inserting a piece of wood up his rectum. Another prisoner, with a gangrenous wound, is eaten alive by cockroaches. Another dies an excruciating death because his urethra is blocked and he cannot pee.

One of the saddest incidents is in the latter years of their imprisonment when the men have managed to secretly contact the outside world and Amnesty International about their existence. It is at this time that Salim falls out with Lhoucine over their families. Lhoucine calls Salim “a bastard” because if he weren’t surely his father, a friend of the King, would have championed their release. Salim angrily responds by asking Lhoucine if he is sure that he is the real father of his son, who had been born nine months and ten days after Lhoucine last had relations with his wife. They trade insults all night then Lhoucine cracks and begins sobbing. He was now a broken man and spent the next few weeks in silence, apart from calling his wife’s name, and slowly wasting away.

Salim is granted access to his cell and begs forgiveness, saying that it was the devil who had spoken that night, not him. But it is too late and Lhoucine dies in his arms.

There are light moments in this novel: those when the prisoners try to make each other laugh with jokes; or when a dove arrives and takes up residence in their cells. They name it Hourria which means Freedom and although they will miss it they know they will have to let it go. In a moving scene they each beg the dove to fly to their families to let them know they are alive.

On another occasion they are in disbelief when the authorities sentence a dog to five years in Tazmamart for biting a general. They name the dog Ditto and laugh until they realise the poor whimpering thing is dieing of hunger, thirst and exhaustion in a cell covered in its own excrement.

Salim is a natural storyteller and recalls poems or books he has read by Victor Hugo and Honore de Balzac, or films he has seen, such as A Streetcar Named Desire. A comrade tells him, “Thanks to you, for a few moments I was Marlon Brando. In my head I walk the way he walks in films. In my head I look at women the way he looks at them in life… I forget who I am and where I am.”

In September 1991, twenty years after the coup, twenty-eight survivors out of the fifty-eight imprisoned in Tazmamart, once again saw the sky, emerged from prison and spoke and wrote about their experience of the blinding absence of light, their time in hell.