A British intelligence officer, Ginge, is lying in hospital in England after just about surviving a booby-trap bomb which exploded under his car outside his cottage near the former coal-mining village of Bloodworth. It is 1994, just months before the IRA ceasefire announcement.

Ginge is protected by MOD police and all visitors are barred, including a former comrade, Eddie. Eddie had served in Aden in the late 1960s and bought himself out of the army but is still haunted by what he and his military friends did to Arab prisoners. He still suffers flashbacks brought on by events in Ireland and the Falklands. Eddie and his wife Amy (a former girlfriend of Gringe) are now working on a commemoration committee to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the miners’ strike which devastated communities throughout Britain. They have undertaken to produce ten display panels, work on which becomes more ambitious and educational as they proceed. (The novel records the scripting of these panels.)

Ginge is protected by MOD police and all visitors are barred, including a former comrade, Eddie. Eddie had served in Aden in the late 1960s and bought himself out of the army but is still haunted by what he and his military friends did to Arab prisoners. He still suffers flashbacks brought on by events in Ireland and the Falklands. Eddie and his wife Amy (a former girlfriend of Gringe) are now working on a commemoration committee to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the miners’ strike which devastated communities throughout Britain. They have undertaken to produce ten display panels, work on which becomes more ambitious and educational as they proceed. (The novel records the scripting of these panels.)

Although Ginge’s father had also been a miner, Ginge had been attracted to the army, then to the Intelligence Corps by a mentor, Geordie, who had served in Kenya and Cyprus. Like Eddie, Geordie also suffered from nightmares about his activities in counter-insurgency, took to the drink and eventually died in a car crash. He had become disillusioned after MI5 had warned him not to raise concerns about Kincora Boys Home where a sex-ring for paedophile politicians and security personnel operated. It was Geordie who told Gringe about rumours that a section of the military brass had a hidden agenda: the same military figures who admired Pinochet’s anti-communist coup in Chile against Allende in August 1973.

Lying in hospital, with plenty of time to reflect, Ginge befriends one of the staff, Elsie, who has a crush on him, and asks her to get him a tape-recorder so that he can put down on record his ‘war’ and details about his Machiavellian superiors, including ‘the Major’ and ‘Snake Eyes’. Ginge had made and kept in his cottage secret copies of an incriminating document written by the Major, ‘Towards a New Britain’, which had also anticipated the creation of New Labour.

Meantime, Elsie and her colleagues are also preoccupied with health cuts and privatisation: the number of nurses are becoming fewer and fewer, the number of managers growing and growing.

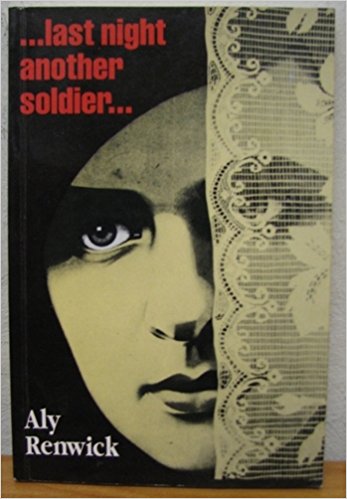

Scottish-born Aly Renwick, a founding member of the Troops Out Movement (and currently a member of Veterans For Peace), has written several books about the British army (see my review of Hidden Wounds here which discusses Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). He also wrote a novel …last night another soldier…, a counter to the British view of the conflict and which was extensively reviewed by Pat Magee in his book Gangsters or Guerrillas which examined the representations of Irish republicans in ‘Troubles Fiction’.

Scottish-born Aly Renwick, a founding member of the Troops Out Movement (and currently a member of Veterans For Peace), has written several books about the British army (see my review of Hidden Wounds here which discusses Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). He also wrote a novel …last night another soldier…, a counter to the British view of the conflict and which was extensively reviewed by Pat Magee in his book Gangsters or Guerrillas which examined the representations of Irish republicans in ‘Troubles Fiction’.

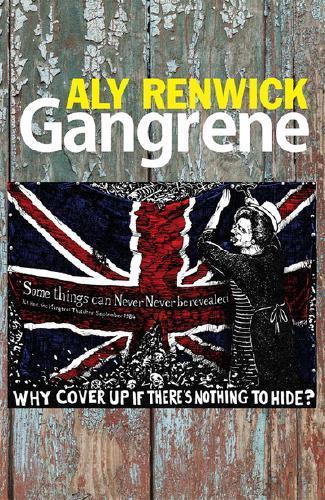

Gangrene is told in alternate chapters of the first-person reminiscences of Ginge as he records them, and a traditional third person contemporaneous narrative. However, Renwick puts the structure of his novel under great stress by expecting it to carry so many stories – potted histories of the British working class, the conflict in Ireland, the dirty war, Tory/Military conspiracies to overthrow Harold Wilson (“a cleansing of the Westminster stable”), the miners’ strike, privatisation, a Stakeknife character, etc. It would have been far better to have concentrated on just one or two elements of those.

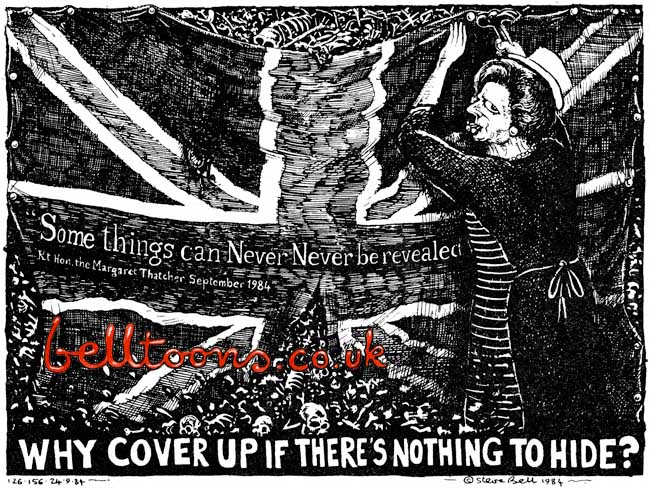

That said, the story does revolve around the ‘cover-up’ of a suspected major conspiracy (later dubbed Clockwork Orange in the press), which could have spilled over into a coup in Britain, and how Ireland was exploited and used as a test case and training ground to further the aims of right-wing Tories, including Airey Neave.

The reader is also alienated by the fact that Ginge (despite, at last, wanting to unburden himself by telling the truth) has absolutely no redeeming qualities even though he likes to think of himself as not being on “any one side”. It is impossible to identify or have any sympathy with him. Nationalists killed on Bloody Sunday were “a pack of … fuckers”. By 1973 he says, “we’d all regarded the prods and ourselves to be on the same side – with the common enemy defined as the micks in general, and the PIRA in particular.” In fact, Ginge is a creep and even went home during the miners’ strike to spy and report on the activities of his friends and neighbours.

The nearest character we can identify with, Elsie the nurse, is too thinly portrayed, even though we can follow her thoughts and that ultimately she emerges somewhat as ‘the keeper of the record’, those confessional revelations by Ginge which the Major thought he had suppressed.

Gangrene is a welcome addition to ‘Troubles’’ fiction and another welcome counter to the usual gung-ho, Boy’s Own crap that receive gung-ho reviews and are promoted in the Boy’s Own mainstream media.

In his last tape, recorded in a hurry, Ginge says: “That thing I mentioned earlier – the Major’s handwritten note about a gangrene threatening the land and them becoming praetorians again. Well, I’m beginning to see a lot clearer now and that’s exactly what he and his mates have done. But it’s them fuckers who are the gangrene – they’re the ones destroying the country and all our lives.”

Gangrene by Aly Renwick, published by The Merlin Press, 2017, £9.99