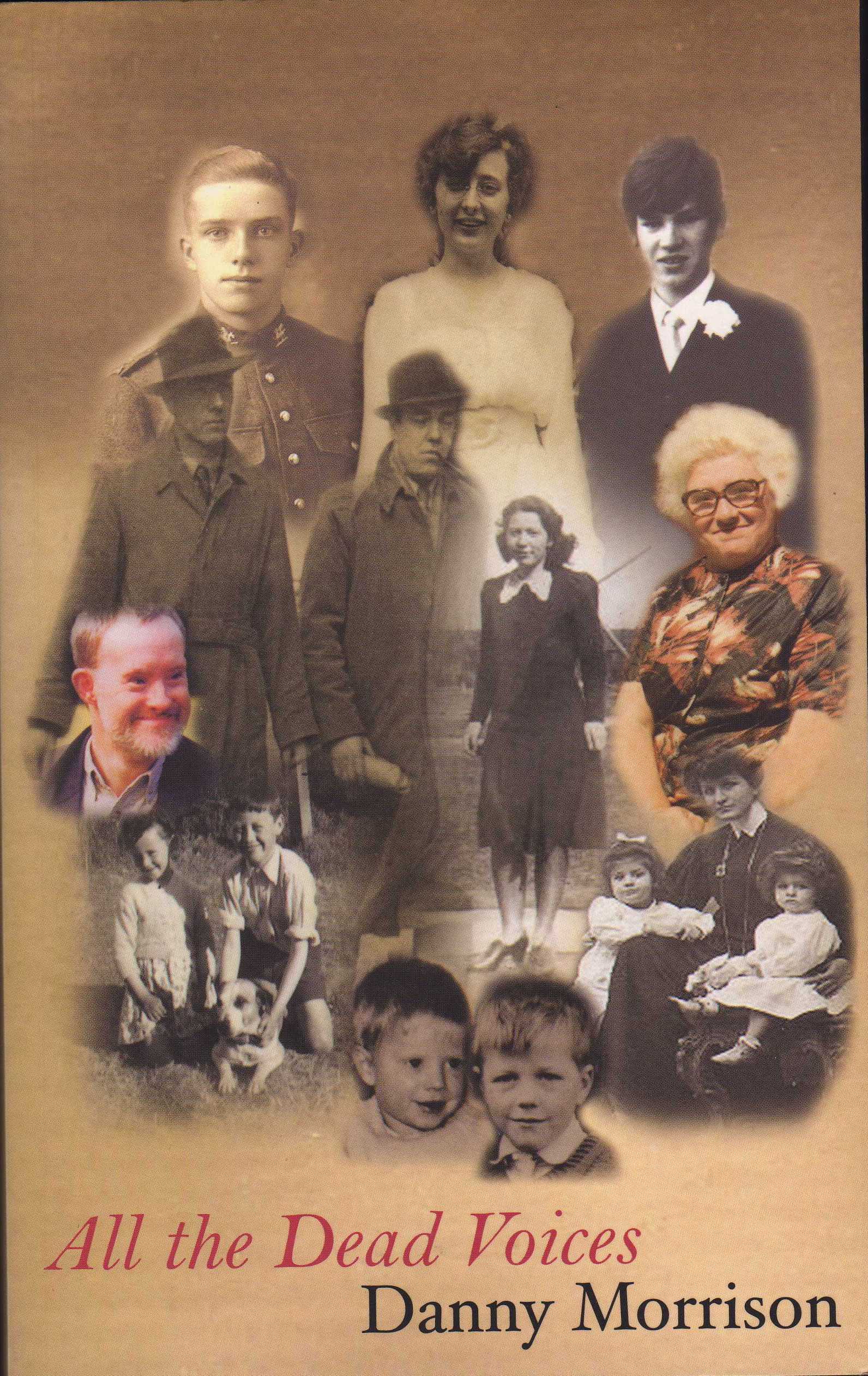

This is from my book, All The Dead Voices, which was published in 2002, and was dedicated to my sister, Susan, who died at the age of forty four. In 1974 Susan moved to Antrim and in 2001 she died in the hospital there from an autoimmune disease, Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. I was cycling to her grave two Saturdays ago, to have a yarn with her, when I was in an accident with a van, and ended up in Antrim Hospital. The PSNI and the ambulance service were brilliant and looked after me and my interests.

-ooOoo-

Driving through County Tyrone on a hot August day we noticed an unusual number of people about as we entered Sion Mills. I wasn’t long out of a Dublin hospital where I had been in isolation for several weeks recovering from hepatitis, and my wife and I with our two boys were heading to Donegal for a break.

There were no cars in front of us but then we noticed people leaving the footpath to walk along the main road. We were about to stop when a policeman at a junction halted traffic from a side street and waved us on, seemingly mistaking our car as part of the procession. Too late did I realise that we had driven straight into a funeral, that of a former RUC man, Thomas Harpur, who had been shot dead by the IRA in Strabane a few days earlier. I was terrified for myself and family, of being recognised and of being thought to be flaunting disrespect. It was an extremely tense ten minutes as we moved slowly through the village, accidentally a part of the cortege.

For over twenty years afterwards I have had a regular nightmare which I am not sure was provoked by this incident but involves my car breaking down in a loyalist area, me being recognised, pursued by a crowd, but always narrowly escaping, usually by suddenly waking up with a scream and in a sweat.

When we were kids my mates and I could go almost anywhere: up the Shankill or down through the loyalist ‘Village’ to get to the Ulster Museum or the Ormeau Park. You just needed to be shrewd enough to pretend to be on your way to your Protestant aunt’s or to adopt a Protestant name, in case you were challenged. Protestant families still lived in our area and sometimes the local Stephenson brothers, who went to school in the ‘Village’, would accompany us as insurance. On Sundays my friend Peter and I explored on our father’s bicycles East Belfast and the countryside out by Holywood, Crawfordsburn and Helen’s Bay along the southern shore of Belfast Lough. We had an old ordinance survey map from the early nineteen hundreds which I got from my Granda Morrison and which we followed. It showed all the old lanes and byways. (Some of the memories from those cycling trips I used in my second novel, On the Back of the Swallow.)

In my forties, against the background of the ceasefires in the mid-1990s, I harboured the notion of going back to see how much those places had changed in thirty years and if the lens of youth had exaggerated the distances we had travelled or the sheerness of the cliffs over which we had shouldered our bicycles. I planned to go to the old haunts, then down the Ards Peninsula to Portaferry, take the boat to Strangford and cycle on through the Mournes, keeping a journal of my journey. I bought a bicycle and trained, sometimes cycling out to Belfast International Airport or around the back roads of the mountains behind West Belfast. But then I got reports that I had been seen in such-and-such a place and that I ought to be more careful. I changed my plans but decided that I would still like to get away by myself, relying solely on pedal power, and do a lot of thinking. I was at a crux in my life and had to make a decision about devoting myself to writing full-time or going back to the struggle, a choice, in a sense, between the individual and the communal.

One of the central themes in Rousseau’s ‘Confessions’ is the tug-of-war between solitude and society, something we all experience to different degrees, and which in Rousseau’s case led to an acute paranoiac breakdown. In his last book, Reveries of the Solitary Walker, written two years before his death at the age of sixty-six, he wrote: ‘… if I am to contemplate myself before my decline, I must go back several years to the time when, losing all hope for this life and finding no food left on earth for my soul, I gradually learnt to feed it on its own substance and seek all its nourishment within myself.

‘This expedient, which I discovered all too late, proved so fertile that it was soon enough to compensate me for everything. The habit of retiring into myself eventually made me immune to the ills that beset me, and almost to the very memory of them.’

Many people can contentedly live off their memories or harmlessly enjoy their own society. It is a form of escapism but is distinct from the introspection of writers, who ruthlessly cannibalise their memories and lives and those of family and friends.

One mid-March, some friends and I spent the weekend in Carlingford. I had brought my bike and did some cycling around the countryside. On Sunday we drove to Fermanagh and they dropped me across the border in Leitrim. I got out at Glenfarn in the middle of a rainstorm with my bike, tent and a sleeping bag.

The rain was so heavy that within minutes it penetrated my waterproof top and leggings and the panniers containing my change of clothes. My map turned to tissue paper. But I didn’t care. The sense of freedom and self-reliance overwhelmed all else.

As Glencar Lake came into view the clouds thinned and the sun peeped out and I ate a bar of chocolate to celebrate. A half-hour later I could see Drumcliffe below. Sligo Bay lit up like a stained-glass window. The road from Drumcliffe, where Yeats is purportedly buried, to Ellen’s Pub in Ballyconnell, where my friend Dermot Healy picked me up, was pretty tough going. Although I had only cycled about thirty-five miles it had been against strong winds coming off the Atlantic. But at least I had a bed for the night in Dermot’s, a whitewashed cottage situated on a small peninsula at the end of a road which is sometimes cut off by high tides. We sat up talking most of the night and Dermot read some extracts from his book, ‘The Bend for Home’, which was to be published at the end of that summer. He and his partner Helen were at a funeral the next day and as work was getting done to their cottage I took myself off and returned that night.

The following day it wasn’t as showery and I set out for Donegal. Just before Ballyshannon there was a travellers’ camp on the far side of the road. A child, sitting on the steps of a caravan suddenly disappeared inside. A man emerged and seemed distressed, waved and called to me. I thought someone had taken seriously ill but I was also cautious. I slowed down and he came running across the road. There wasn’t another person or car in sight. As he got closer he appeared fierce. I shouted out, ‘What is it? What do you want?’ He had a mop of ginger hair and a huge ginger beard and I became alarmed and began pedalling furiously. He shouted something about cigarettes and money and almost caught the bike by the saddle, except that I was swifter. When I looked back he was standing in the middle of the road cursing. I was on adrenaline for the next five minutes and when I stopped I was shaking, felt stupid and a coward and reckoned this was probably the way he menaced passers-by for money or a smoke and I should have just given him something.

I had an awful dinner in Donegal town and wasn’t sure whether to pitch the tent or look for a B & B. It was still light so I pushed on and a few miles outside Mountcharles took the mountain road for Glenties. Night dropped like a stage curtain and the first stars appeared. When cycling during the day the luxury of light and detail and facility to focus had me conscientiously making what seemed like important adjustments to the steering to avoid a minor hole, a twig on the road or the verge. Guided now more by instinct than by the pathetic light of the dynamo-driven lamp, I had no mishaps, trusted in God and was thrilled at recklessly speeding down hills in almost complete darkness. Sometimes I whooped and cheered.

That day I had cycled sixty miles and arrived in Glenties at ten at night as the bingo crowd was getting out. I asked among the people where I could pitch my tent and was told that if I went to the Parochial House I would get permission to camp in a wood above the school. I did that and pitched the tent. Then I went into town for a couple of pints. The bar was empty. They must have known I was coming.

It was a freezing night, there was a ground frost, and I slept only towards dawn. At about half eight sticks and stones rained down on the tent and a crowd of kids in the schoolyard were shouting, ‘Get out of there, you knacker!’ I sprung up, ran on to the playground and gave them a dressing down for their intolerance. I’m sure they thought I was a madman, sleeping out in such weather. I told them that for all they knew there could have been a child in that tent who they were terrifying or could have injured. Two of the kids – boys, I noticed – sniggered. I turned on them and told them I was from Belfast and that if they ever came into my area we would welcome them, not attack them. I turned and walked back to the tent and began dismantling it. A few minutes later a couple of kids came up to me and said they were sorry; then their teacher appeared and also apologised.

For breakfast I had two bananas and a pint of milk. The sun came out and I was on my way, listening to the radio through earpieces and laughing at a new song which went something along the lines of, ‘Aon focal, dha focal, tri fhocal eile…and I not knowing no fuckell at all.’

The air was filled with the smell of turf, the skies were blue, I was free and healthy: I was inside my own soul. I arrived in Dungloe, locked my bike and wandered the main street. I called into a store owned by a man with whose brother I had been in jail but he was not there that day. I treated myself to a big meal and a few glasses of wine.

A friend, Pam Brighton, director of Dubblejoint Theatre Company, who lives in Belfast, owned a bungalow a few miles outside Dungloe and told me I could collect the key for it from next door. I went out to the house, got the key and spent a lonely night. I rose very early the next morning, had some toast and milk and set off for Letterkenny, thirty Donegal miles away. There was a biting wind and flurries of snow as I made my way around Errigal Mountain. My hands were numb, even through strong gloves. But the road from Kilmacrennan to Letterkenny was a back-breaker, long and steep and never-ending. When I arrived in Letterkenny I decided that I was mad, it was still winter, I was beginning to feel miserable and I was very, very tired and wet. I went to the bus station and asked could I put my bike in the luggage hold to get to Derry. There was no problem.

In Derry I thought about staying the night in someone’s house and trying to complete the return journey to Belfast, seventy miles, in one go the following day. But when I heard that there was one more train to Belfast that night, leaving within a half hour, I decided to go home. I phoned my sons and told them to expect me in about two hours, quickly ate an awful hamburger, then flew over Craigavon Bridge to the station on the Waterside. I put my bike in the freight compartment and sat down in the adjacent carriage. I had a few days growth on my face and was wearing a woolly hat. I put on my Walkman to listen to some music, spread myself across the seat, felt a modest glow of accomplishment and began to doze.

As it turned out the train was not an express but was destined to stop at all of the stations along the way. It pulled up at Castlerock, scene of the sectarian killings of four nationalists as they arrived for work in their van, three years earlier. I watched as a number of men on the platform climbed into the freight compartment and passed in golf bags. Then, the door into our compartment was opened and in came the five of them carrying, which I hadn’t noticed, plastic bags full of cans of beer. One of them had what looked like a loyalist tattoo on his arm. They couldn’t get sitting beside me – I was pretending to be asleep – but one burly fella ripped the seat opposite me out of its fittings. They proceeded to sit just across the aisle and use the seat as a card table. I buried my chin deep into my shoulder, away from them.

‘Hey boy!’ One of them shouted over. ‘What are you listening to?’

I realised that they were drunk. I overheard that they were from Lisburn.

‘How many fuckin’ cards do you want?’

‘Givus two fuckin’aces, okay!’

‘I know your man from somewhere.’

Then it was back to the game.

Every few minutes one would say, ‘I definitely know him. Billy, who does he remind you of?’

The sweat was trickling down my neck and I knew I was in for a severe beating or worse if they realised who I was. This went on for about twenty minutes. At one point while they were arguing over the poker I rose quickly, as if just realising it was my stop, and went into the freight compartment.

‘What do you think you’re doing! You can’t stay here,’ said the conductor. ‘It’s against regulations.’ I told him that the men next door were drunk and bothering me.

‘Well, there’s plenty more seats down the carriage. Go down there,’ he told me. But I knew if they saw me face-on they would probably recognise me. Nor could I confide in the conductor about my true concern as his loyalty was unlikely to lie with me, and, besides, he was only one man. I asked where we were. He said, Cullybackey. I asked him what was the next station and he said Ballymena. I told him I would get off there.

‘But there’s no more trains back to Belfast tonight,’ he said. I told him I didn’t care.

I got off in Ballymena. I was starving, tired and frightened. Antrim was eleven miles away. Refuge in a friend’s house (Susan’s, though I did not publish this at the time). The night was now black. It was cold and drizzling and there seemed to be a thousand cars recklessly roaring past me. After about an hour I made it to Antrim but was confused and couldn’t find my friend’s house. I was afraid to ask in case I was in a loyalist area and, again, someone might recognise me. I couldn’t even go into a phone box or a shop for a drink and food. I realised that I would have to cycle to Belfast, nineteen miles away along back roads. I came through the loyalist Ballycraigy estate to get onto the seven-mile-straight.

I was now so dehydrated that out in the countryside I lay down on the road and gulped rain water from a puddle and noticed glistening cow dung just a few feet away but didn’t care.

I shivered as I rode past the ghostly spot, marked by a cross, where two Protestant brothers, Malcolm and Peter Orr, were killed by loyalists in the early days of the Troubles because they had befriended Catholics. I found a small stream, climbed down an embankment and drank about two pints of fresh water out of my cupped hands. There was a long hill before me, the top of which was shrouded in mist. I was too tired to cycle up it so I pushed my bike for about fifteen minutes. Dogs barked and howled as I passed a few isolated houses.

At a quarter to one in the morning, having been on the road for over sixteen hours I turned onto the Tornaroy Road at the back of Black Mountain and with relief saw the lights of the city glint below. It was all downhill now and when I arrived home I discovered that while I was in Ballymena the UVF had burst into a pub and shot dead one of their members, Thomas Sheppard, as a suspected informer. My sons had heard about the shooting and had been very worried when I hadn’t arrived as expected.

Regrettably, but understandably, there are hundreds of places in this my own country where I, and others with thumbs in the conflict, will never be safe or able to visit, despite ceasefires, power-sharing or our support for peace.

Except, perhaps, in old dreams of youth. And nightmares.