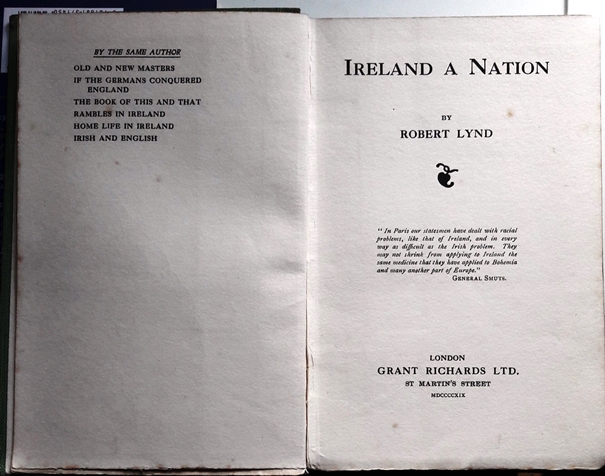

For Christmas, my old friend Tom Hartley gave me an old copy of an old book written in 1919, Ireland A Nation by Robert Lynd, who was born into a Presbyterian household in 1879. In my book All The Dead Voices I devote a chapter to Lynd who was buried in Belfast’s City Cemetery in 1949.

Lynd became an Irish republican but was opposed to physical force, believing that violence would alienate the unionists, for whom he always maintained a great affection.

His funeral was remarkable because of the large number of dignitaries it attracted from different walks of life, showing just how well he was regarded. Among the mourners were his old school friends, Air Vice-Marshall Sir William Tyrrell; Sam Porter, then Lord Chief Justice; Lynd’s nephew, Robert Lowry, a future Lord Chief Justice (who in 1978 would acquit Gerry Adams of an IRA membership charge); the artist William Conor; the former IRA Chief of Staff, Sean McBride, then Minister of External Affairs for the Dublin government; McBride’s assistant, Conor Cruise O’Brien; and Senator Denis Ireland.

Robert Lynd was born in North Belfast in 1879. His father, a Presbyterian minister and former Moderator, was an anti-Home Ruler. Robert, though, declared himself a socialist, became a fluent Irish speaker and later became a republican.

He worked in London as a journalist and while there got to know Michael Collins. He taught Roger Casement Irish and was one of the most active petitioners for Casement’s reprieve in 1916, visiting him in Brixton Prison.

He was a member of Sinn Féin for a while and also wrote the introduction to James Connolly’s book, Labour in Irish History, which was published in October 1916 after Connolly’s death and Casement’s execution. About England, in his introduction, he had this to say:

‘She left Home Rule in a state of suspension, which was apparently meant to enable nationalists to pretend: “All will be well at the end of the war,” and to enable Ulstermen also to pretend (in an entirely opposite sense), “Yes, all will be well at the end of the war.” Thus, at the outbreak of the war, while England was given a great ideal, Ireland was given only a lie. Thousands of Irishmen, no doubt, insisted on making the great ideal their own, and in dying for it they have consciously laid down their lives for Ireland. But others were unable to see the ideal for the lie, and they too of set purpose laid down their lives for Ireland. To blame Ulster for all this is sheer dishonesty. It is not Ulster, but the British backers of Ulster, who must bear the responsibility for all that has occurred within the last four or five years in Ireland. Ulster would have come to terms with the rest of Ireland long ago if the unionist leaders and the cavalry officers of the Curragh had told her plainly that she could no longer reckon on their support. The Ulster problem is at bottom not an Irish problem but an English problem; and it is for England to settle it.’

Lynd was also a great admirer of Lieutenant Tom Kettle, who died at Ginchy, and of Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin, about whom he wrote: ‘His mind was in one sense narrow: he was capable of bitter injustice to political opponents. At the same time, he had a large-minded conception of nationality and wished to create an Irish civilisation that would be as acceptable ultimately to the old unionists as to the nationalists.’

Lynd, who never lost his Belfast accent, remained in London, writing for the New Statesman and the News Chronicle. He was described as a tall figure that walked through London with an untidy appearance, his pockets full of newspapers and books. When James Joyce and Nora Barnacle got married in 1931, their wedding lunch was held in Lynd’s home. A friend, H. L. Morrow, said about him: ‘He had an incessant interest in other people’s lives and points of view. I have champed impatiently while he chatted (at utter random it seemed) with a beggar, a waiter, a bus conductor, about tomorrow’s race meeting at Kempton Park, the Budget or last night’s thunderstorm. A week, a month, maybe a year later, it has all come out, out in a ‘Y.Y’ essay [his pseudonym in the ‘New Statesman and Nation’].’

One of Lynd’s favourite stories was of a stranger to Belfast who, seeing a crowd gathered after a street accident, asked one of them what had happened. ‘Afallafallaffalarri,’ he was told. The stranger repeated his question and was given the same answer, which he thought was in Gaelic until someone explained that, ‘A fella fell off a lorry.’

Lynd published over thirty books, was ranked alongside the essayist Max Beerbohm, yet apart from a rearguard rescue of some of his essays by Sean McMahon and Lilliput Press in 1990, he has been neglected and is even excluded from Field Day’s monumental Anthology of Irish Writing.

Lynd drank, loved gambling and smoked one hundred cigarettes a day. He still kept an eye on his native soil. He wrote: ‘I never thought of the Ulsterman as the grim dour figure that he is sometimes painted.’ Shortly before his death he wrote to the press condemning the campaign of the Anti-Partition League as ‘highly inflammable’.

The APL was established after a meeting in Dungannon on 15 November, 1945, called by Stormont MP Eddie McAteer (a brother of Hugh McAteer, the former IRA chief of staff). The Socialist Republican Party and the Ulster Union Club – both of which had had a substantial Protestant membership – who had not been invited denounced the meeting as a ‘sectarian manoeuvre’. The APL thus represented Catholic small businessmen and professionals, was clergy-dominated, conservative, and its support was largely rural. Its election candidates were financed from Catholic church gate collections and by the southern political parties. In response to the declaration of a republic by the Dublin government and the APL, the Stormont government called a snap election in February 1949 and successfully exploited the fears of Protestants to consolidate its position.

During the election there were sectarian clashes and violence from which Lynd recoiled. An uncle of mine, Hugh Downey, who was a Stormont MP and Vice-Chair of the Northern Ireland Labour Party lost his Belfast Dock seat to the UUP when the intervention of a young Sam McAughtry split the left vote.

Lynd died in London of emphysema, at the age of seventy, on October 6, 1949. There were tributes from G.B. Shaw and Sean O’Casey. His remains were removed to Melville’s Private Mortuary, Townsend Street, Belfast, and he was buried on the Falls Road at half past eleven on the morning of Monday, 10 October. The Union flag at Inst. College, his old school, hung at half mast. His wife was too ill to attend but a daughter and three surviving sisters were present at the interment.

Many years before his death he wrote: ‘I should have felt a sharp pang if it had been foretold that I should be buried anywhere except in my own country, and I was particular even to the exact spot in that… It seems as though we must be surer that life is worth living than that dead is worth dying. But, even on this matter, there is room for hope.’

Robert Lynd was a united Irishman, if ever there was one.