I wrote this feature in May 2005: some thoughts about perennial war and how people rationalise their justifications for their actions.

I was reminded of it when I saw on Twitter today a reference to Robert Oppenheimer (the American theoretical physicist in the Manhattan Project) who became known as “the father of the atomic bomb”. After all the deaths he remorsefully said of himself, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”, a quote from the Hindu sacred text of the Bhagavad-Gita, though many treated his contriteness cynically. Anyway, here is my feature from thirteen years ago.

Most people, one would think, would not hesitate to condemn the boiling alive of an individual or the roasting alive of a hundred thousand individuals. Yet war, and the side one supports, often leads to perverse ambivalences, excuses and justifications.

Last Friday five hundred civilians, protesting against religious persecution, poverty and unemployment, were shot dead in Uzbekistan whose autocratic ruler, President Karimov, is a close ally of George Bush and part of ‘the coalition of the willing’. US forces are stationed there in strength and used the country as a base for the war against the Taliban in nearby Afghanistan.

Furthermore, suspected members of al Qaeda have been brought (‘rendered’) to Uzbekistan by the US for ‘special’ interrogations, using methods outlawed in the US.

In return the US has turned a blind eye to the repression of those Muslims who practise their faith independently of Karimov’s state controls. As a result of this repression they are increasingly attracted to and radicalised by the underground Mosque movement.

Two years ago Human Rights Watch published horrific photographs of Muzafar Avazov, a father of four, showing sixty to seventy per cent of his body covered in burns.

Later, Craig Murray, the British ambassador to Uzbekistan, spoke in London about having seen “the pictures of Avazov, with Amizov [another prisoner] boiled to death in Jaslyk prison. The University of Glasgow pathology department studied the detailed photos and concluded that this was immersion in, not spattering with, boiling liquid. There was a clear tidemark. The fingernails had also been pulled,” said Murray.

Murray described Uzbekistan as having “no freedom of the media, no freedom of religion, no freedom of speech and no freedom of assembly.” He criticised Bush’s meeting with Karimov, and other high-level delegations to the capital Tashkent by Donald Rumsfeld and Colin Powell, during which there was no mention in public, nor did he believe in private, about the country’s appalling human rights’ record.

Murray queried the morality and legality of Britain accepting clearly tainted intelligence information from the Uzbeks: “What absolutely terrifies me is the thought that such poor intelligence material, endorsed by someone in the last gasps of agony [is] given credence by some gung-ho Whitehall Warrior.”

After these outspoken comments and criticism of the US, Tony Blair removed Murray as British ambassador to Uzbekistan.

Bush and Rumsfeld, by patronising and protecting Karimov (from criticism at the UN Commission for Human Rights in Geneva), must bear some degree of moral responsibility for the repression in Uzbekistan. Yet, they would probably argue that the ends (defending their nation from terrorism) justify the means (their use of state terrorism, and allying themselves with a terrorist state – though they would object to that description).

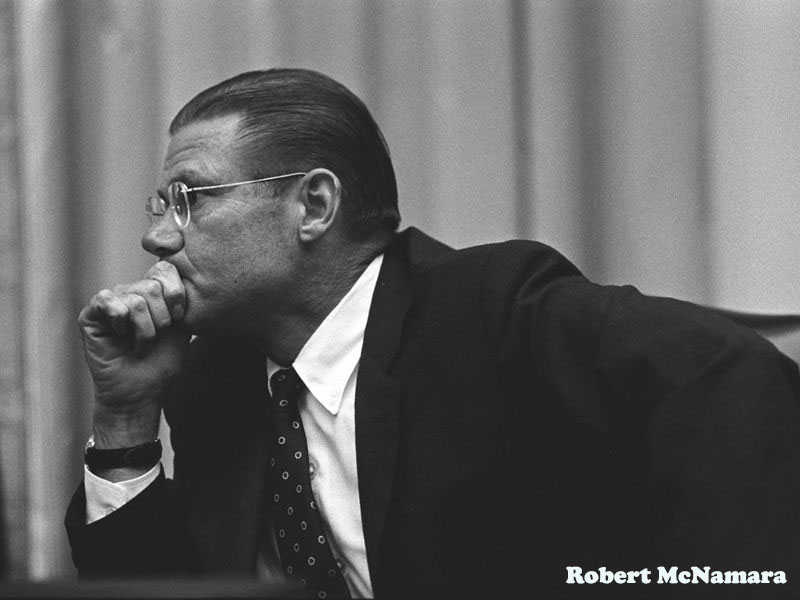

Last Sunday BBC2 broadcast the 2003 Academy award-winning documentary, ‘The Fog of War’, about Robert S. McNamara, a former Lieutenant Colonel in the US Air Force during WWII and US Secretary of State for Defence (1961-68) during the Vietnam War.

It was a fascinating insight into the 86-year-old McNamara’s reflections on war and of a disturbing mentality which can justify the mass slaughter of civilians, and, later, put it and one’s regrets down to experience.

“In order to do good, you may have to commit evil,” was one of his eleven lessons from his life, which sounded like Machiavelli paraphrased.

During World War II McNamara was a bombing statistician under General Curtis LeMay and supported the carpet bombing of Japan which in one night resulted in the burning to death of 100,000 civilians. It was terrorism by any definition.

It was also under LeMay’s command that the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The government’s defence was that the Japanese would fight to the death and kill scores of thousands of the invading US marines. In other words, our American soldiers were more important than their Japanese wives and children. I don’t know what view I would have adopted had I been an American marine or the father of one. But at that point the interests of the tribe, not humanity, reigned supreme. At the time of the A-bombs Japan was militarily broken and the use of the bombs was a powerful demonstration to the USSR of the prowess of the USA.

McNamara recalls LeMay later saying, “‘If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.’ And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognised that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose, but not immoral if you win?”

Well, the victor usually gets to write history and make the law, which is why the Allied bombing of German and Japanese civilians were specifically excluded from the list of war crimes developed for the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials.

McNamara was an advisor to Kennedy at the time of the Cuban missile crisis when the world came close to destruction. But it was because of McNamara’s involvement in and defence of the war in Vietnam, first under Kennedy then under Johnston, that my generation despised him. Millions of Vietnamese and 55,000 Americans died in that war. There was no threat to the American people and lies were told to sustain the war.

McNamara regrets that it happened, admits that mistakes were made and that they didn’t really understand the Vietnamese but resists accepting responsibility for his actions apart from questioning whether humankind is able to learn anything from history.

All the while he seeks the comfort of humans as flawed individuals: “Any military commander who is honest with himself, or with those he’s speaking to, will admit that he has made mistakes in the application of military power. He’s killed people unnecessarily…”

And so, the lesson that supporters of the US and Britain’s war-on-terrorism need not balk at is that under the fog of war occasionally prisoners will be boiled to death unnecessarily. Such acts are to be regretted and, yes, mistakes will be made. But we have to appreciate the wider picture and that in order to do good we have to commit evil.