In the early days of the northern conflict, former Lieutenant-Colonel Colin ‘Mad Mitch’ Mitchell was asked for his advice on how to cope with the IRA.

In the early days of the northern conflict, former Lieutenant-Colonel Colin ‘Mad Mitch’ Mitchell was asked for his advice on how to cope with the IRA.

“The weapon I should like to introduce is the gun inside the television camera. I mean, what I’d like to do is to have a machine gun built into every television camera and then say to the IRA ‘Come out and let’s talk’… and then shoot the lot. Hypothetically, if the Prime Minister – it would be the wisest thing he ever did because he would get the thing off his chest – if he said to me tonight, ‘Mitchell, you are going to Ulster to sort this thing out, what do you want? I should say, ‘Well, the first thing I want are full powers (like Harding in Cyprus and Templer in Malaya) and these full powers would be, first of all, the death penalty for carrying arms.”

Mitchell said he would hang republicans in prison or just start shooting them. “…by the time you have knocked off ten, take my word for it, the other ninety will be in Killarney. They’ll go. They can’t stand up to it. So you have solved the problem.”

Mitchell believed that “it was entirely right that the British should rule a large part of the world.”

And almost every part of the world which Britain ruled kicked them out, the natives not appreciating the ‘civilising agenda’ that was their reward for handing over their land, their labour, their oil, their ports, their language and culture to the British.

I don’t know enough about modern Yemen and the current power struggle being played out in the once busiest ‘British’ port of Aden (first occupied in 1839 as a refuelling station for ships heading to India) except that mistrust and old rivalries again have the various groups in Southern Arabia at each other’s throats.

A Sunni President, recognised by the ‘international community’ (usually code for western interests), has been displaced by Shia Houthi rebels. The beleaguered President is supported by Saudi Arabia which has been bombing both civilians and the rebels who are supported by Iran (Saudi Arabia and Iran being the major regional powers). To complicate matters, the President and the Houthis are opposed by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which, has long been the subject of a US drone war. To further complicate matters all of the above are opposed by an affiliate of the Islamic State (ISIS/ISIL) which seeks to eclipse AQAP.

It’s a nightmare. Just days ago gunmen stormed a Catholic retirement home in Aden, opened fire and killed at least sixteen people, including old people, nuns, cleaning staff and security guards.

The most recent book on Aden has been written by the historian Aaron Edwards (from Belfast). Edwards interviewed me in 2010 and 2012. On the first occasion he was a Visiting Research Fellow in Politics at Queen’s University and was researching the British Army’s information policy in the 1970s and 1980s and the connections between British military operations and political approaches in the colonial contexts of Palestine, Malaya, Kenya, Cyprus, Aden and the north of Ireland. On the second occasion he was a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Huddersfield and was planning to write a book, with the working title, Britain’s War Against The IRA.

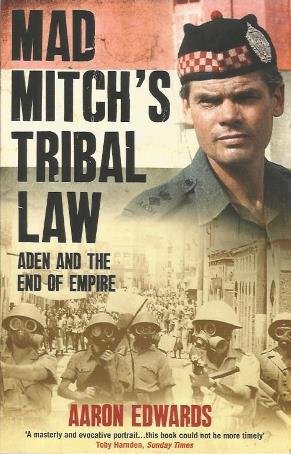

Since then he has become a Senior Lecturer in Defence and International Affairs at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. No surprise therefore that his latest book, Mad Mitch’s Tribal Law – Aden And The End Of Empire*, reads as if it is being addressed to British military students.

Although Edwards includes many criticisms of his subject, Lietenant-Colonel Colin Mitchell, Commanding Officer of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, the book is somewhat of an apologia for the controversial officer, who was so controversial (especially over the Crater affair, of which more later) that Britain refused to decorate him. Ironically, Mitchell, although later a Conservative MP for four years, subsequently set up his own company and did productive work (and presumably not as a spy) clearing land mines from war-torn countries.

My interest in the book was to look out for parallels, comparisons and contrasts between the British government and British army’s behaviour in Aden, and its behaviour in the North of Ireland.

In 1962, in the capital Sanaa, radical army officers overthrew the ruthless, conservative regime of Ahmad bin Yahya Hamidaddin and established the Yemen Arab Republic. Britain, Saudi Arabia (and Israel) armed and financed the dethroned royalists and their mercenaries. Beyond, and including British-controlled Aden, the British Conservative government established the puppet state of the Federation of South Arabia. (The Conservatives lost the 1964 general election and Labour’s Harold Wilson then became Prime Minister.)

Two groups opposed the British: the National Liberation Front (NLF) supported by Egypt’s Nasser (until 1965); and its rival, the Federation for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY). Their campaign of assassination, ambush and bombing undermined the morale of the pro-British Federal Regular Army, the Armed Police and the civil administration. The insurgents wanted unity. The Aden Trade Union Congress also opposed the Federation. Its newspaper was closed down, its general secretary and many members were arrested and interned. During a general strike in 1962 the British army fired on marchers, killing a demonstrator.

Only 3,666 miles from home, in a country into which they were not invited, here is the arrogant mentality which fuels imperialism: “Arabs should not be left to their own devices”; the Arab was “half rational, half mystical, and wholly oracular.” One British soldier cut through the pretence: “We treated everyone as the enemy.”

Only 3,666 miles from home, in a country into which they were not invited, here is the arrogant mentality which fuels imperialism: “Arabs should not be left to their own devices”; the Arab was “half rational, half mystical, and wholly oracular.” One British soldier cut through the pretence: “We treated everyone as the enemy.”

Whilst Edwards does concede that some tribesmen showed “great courage and skill’ and were “expert guerrilla fighters” his terminology in the main reflects that used by the imperialist: those opposed to the British were ‘subversives’, ‘terrorists’, ‘ruthless individuals’, whereas the SAS men have “cool heads and steady nerves”. And, of course, the padre was always there to assure the soldiers that “God is on their side”. What a laugh.

The marxist NLF carried out most of the attacks such as assassinating government and administrative figures, attacking and killing by bomb and grenade soldiers drinking in bars, or in the Officer’s Mess (killing, on one occasion, the 16-year-old daughter of a medical officer). The RAF retaliated by bombing villages and rocketing ‘the odd house’.

What is interesting is that many of the chief protagonists on the British side had earlier been involved in other counter-insurgency campaigns. They just can’t get enough of it. Sir Richard Turnbull, the High Commissioner “was relentless in advocating what he regarded as tried and tested ‘experiences’ with Mau Mau terrorists in Kenya.” It was under Turnbull that “a special programme of interrogation began to extract whatever paltry intelligence could be gleaned from detainees.”

During its time there, the British army set up a covert ‘Special-duties squad’ or the Special Branch Squad which operated independently of the main army command, and dressed in civilian or Arab clothes. Sounds like MRF and FRU, doesn’t it, or the Cairo Gang? It was claimed that “they arrested suspects, captured and killed grenade throwers and gunmen, and discovered huge quantities of arms and ammunition.”

Given what we know of the methods deployed by undercover soldiers in the North we can reasonably guess the saintly way they carried out their duties. In Aden the Colonial Courts did not have the authority to try members of the armed forces for ‘offences against the law of the territory committed whilst on duty.’ In the North the state protects its actors through the use of Public Interest Immunity Certificates.

Just think, only four years after being humiliated and driven out of Aden, where it acted repressively, with shoot-to-kill incidents, and had interned many people (including trade unionists), Britain was introducing internment in the North and once again torturing detainees (as it would do in Iraq in the early 21st century).

In Aden the British established a secret network of detention centres (just as there were such centres for the ‘hooded men’ in 1971). For Fort Morbut Interrogation Centre, from which could be heard “bloodcurdling squeals”, read Castlereagh. Medical records frequently note detainees suffering perforated eardrums – a similar and regular type of injury reported by Dr Erwin about Castlereagh detainees. In Aden it was ‘advanced interrogation’ methods; in the North it becomes ‘deep interrogation’. The ‘five techniques’ of interrogation (including the use of ‘white noise’) used against Yemeni and Irish prisoners were first practised by the British in Brunei in 1963.

At the time of the allegations of torture in Aden, the British government came under pressure to order an inquiry, and even refused to let journalists interview those who claimed to have been tortured. The allegations of torture were, alleged the government, part of a dastardly smear campaign! The same defence that was to be used in the North and faithfully repeated by a compliant mainstream media.

Later, the government appointed Roderic Bowen QC, a former MP and Deputy Speaker of the Commons. A safe pair of hands, like Widgery. His task, though, was not to investigate allegations of torture but to come up with recommendations for dealing with complaints by detainees in the future! He patriotically reports that “the allegations of torture were found to be overblown.” Bowen said: “I certainly gained the impression that speaking generally they [the interrogators] discharged their onerous duties with great restraint.”

The North had its very own Roderic Bowen report. Sir Edmund Compton’s 1971 Report into allegations of the torture of detainees ruled that “none of the forty complainants whose allegations the committee had investigated ‘suffered physical brutality as we understand the term’.” Prisoners (having been thrown out of helicopters) and being forced to run over broken glass and barbed wire to get away from snarling Alsatians “may have suffered some measure of unintended hardship.”

What about prisoners being forced to do press-ups for hours on end to avoid being beaten? This “must have caused some hardship but [we] do not think the exercises were thought of and carried out with a view to hurting or degrading the men who had to do them.”

And that is why, when it comes to investigating the past and British violations of human rights and the right to life, it cannot be left to the British government to set the terms, to nominate the judicial investigators, their own cronies.

Edwards is honest enough to describe what happened, or reports or allegations about what happened (“sometimes brutal, interrogations…”), but is loath to conclude that these methods, repression, state torture, murder – are the norms of British imperialism, indeed any imperialism. These immoral methods were the only way the empire could have been established and sustained. So, unless you teach these truths to your soldiers your army is condemned to repeat over and over again the same tried and failed measures, and poor people around the world will continue to suffer and die from the same imperious mentality.

When in 1967 the police mutinied (described as ‘Arab disloyalty’) and attacked the British army, the army was temporarily withdrawn from the rebel stronghold of Crater, home to 70,000 Arabs.

Brendan Behan use to say, “I have never seen a situation so dismal that a policeman couldn’t make it worse.”

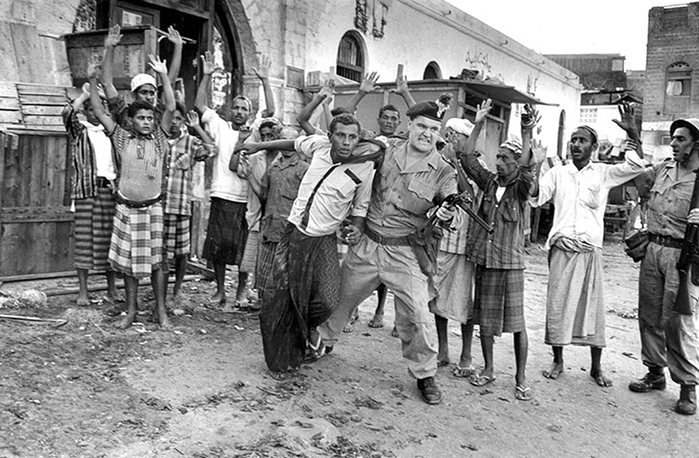

And so into Aden struts that very peeler, Colin Mitchell, later described by the Daily Express in what it thought was a flattering epithet as “Mad Mitch”, head of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

Back in Britain Defence Secretary Denis Healey (one of those “squeamish politicians” according to Mad Mitch), could see that the writing was on the wall and that the empire was actually a liability. They were committed to a policy of decolonisation, preferably installing a government sympathetic to British economic interests. They announced their intention of giving South Arabia (consisting of the colony of Aden and the Federation of South Arabia) its independence by 1968 but were actually forced out and humiliated in 1967.

But before withdrawal, Mitchell’s position was that ‘disloyal Arabs and their terrorist bedfellows’ needed to be taught a lesson. Operation Stirling Castle involved his soldiers retaking Crater (for 144 days), entering Mosques without permission, and bayoneting civilians whom they described as ‘wogs’ or ‘gollies’.

Mad Mitch – ‘protector of the empire’ – loved the press, the publicity. He was a megalomaniac. And delusional: “The Argylls did the best they could to ensure life carried on as normal: that children could get to school, that bills were paid and that food got to the market.”

In 1981 a former soldier admitted that they had been involved in a litany of murder, thefts and wilful criminal damage, and looting; that they stripped the dead of money belts and other valuables. Another soldier later suggested that they slaughtered civilians in Crater as they queued for water at stand pipes.

This was “gruesome stuff”, says Edwards, but was “never substantiated”.

Never substantiated, especially given that a committee of two administrators and a Special Branch officer before withdrawal began burning Aden’s incriminating files, whilst other files sent to London remain under seal to this day.

British servicemen, said Mad Mitch, were ‘Britain’s best ambassador’! Their objective was “to bring ideas of democracy, peace, prosperity and freedom to those who needed our help,” but who didn’t want it or asked for it.

You couldn’t make it up.

You could not make it up.

*Mad Mitch’s Tribal Law – Aden And The End of Empire by Aaron Edwards is published by Mainstream Publishing, £8.99