The British radical left and their prodigious publications in the 1970s were quite influential on young northerners like myself and introduced a new generation to voices like Frantz Fanon, Albert Memmi, Patrice Lumumba, Julius Nyerere, and Aimé Césaire, to name but a few.

I was once given a present by the activist Liz Curtis (author of Ireland The Propaganda War) which, initially, was strange because it was about cricket! However, Beyond A Boundary was more than that. Ostensibly, ‘the finest book’ written about the English sport, Cyril Lionel Robert James in his memoir linked cricket, race, class and anti-colonialism. In simple terms, the West Indian-born James, who became intrigued with the game as a child in Trinidad, viewed cricket not just in terms of technique but from a social/political perspective. He wrote:

‘The God damned English writers with their elms and their green lawns and church steeples and eleven men playing cricket and the Englishness of it etc. etc, are all going to be thrown in the dustbin. They have to explain why in India, in Ceylon, in the W.I. and in places where there are no elms and there are no church steeples but mosques and tom toms the game is played with more fanaticism than in England.’

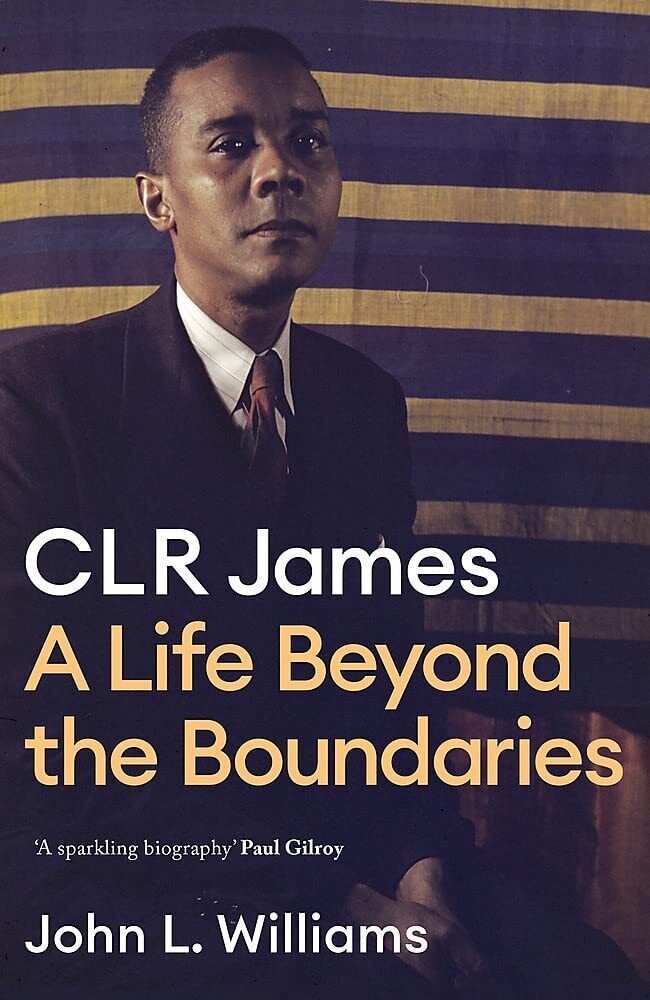

Despite James’ many critics, from the left and right, this comprehensive 2022 biography by Williams proves the staying power and influence of the charismatic Trotskyist activist who died aged eighty-eight in London in 1989. Even in the last five years of his life the devotees flocked to his bedside to learn from the elder statesman whose intellect remained undimmed, though he never suffered fools. In these last days he also enjoyed the company of cricketers such as David Gower and his favourite, Ian Botham.

Though more a paean than a hagiography Williams cannot and does not shy away from his subject’s arrogance, sense of entitlement, how obnoxious, precious, sexist and predatory with the wives of friends and colleagues, James could be, particularly during his long stint with the Socialist Workers Party and the Negro Bureau in the USA, before the various splits to which he, the purist, contributed.

Of one woman, a potential lover, he wrote: ‘She needs to go to a hairdresser and get a good hair-do to begin with.’ In something of an understatement William writes, ‘he did not always live up to his own standards in his personal life.’

James believed in the leading roles that blacks, women and the youth could play in struggle but that it must be anchored first and foremost in ‘class’ politics. He predicted the demise of the USSR, and in light of George Floyd’s recent killing his 1967 words resonate with a certain prescience – that the real enemy of blacks in the US is not white people but the police, the armed wing of the state.

James was a man of many contradictions. An early advocate of women’s equality he thought nothing of groping his secretary or of his married mistress undergoing two abortions in quick succession. James could ignore family, siblings, wives and children because of his incredible self-belief, his ego and his devotion to the cause. His second wife, Constance Webb, twenty years his junior, is a remarkable woman in her own right. Theirs was a mixed marriage and they suffered much racism in north America. The letters James wrote her over many years are the most revealing about his early life, his politicisation.

In Trinidad he grew up in a middle-class milieu and put his aloofness and distrust of women down to the beatings inflicted by his Puritan father. He left for England in 1933 to become the famous sports commentator and moved in radical political circles. Such was his renown as a great intellectual that he was invited by Kwame Nkrumah to Ghana’s independence celebrations, dined with Martin Luther King, was friends with writers Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, and was visited by the writer Alice Walker in later years.

He went on to write one of the great epics of revolutionary struggle, The Black Jacobins, about the 1791 twelve-year long revolt by half-a-million slaves in the French West Indian colony of San Domingo, led by Toussaint

L’Ouverture. The rebellion resulted in the establishment of ‘the Negro state of Haiti’, the only successful slave revolt in history.

That work, his other brilliant speeches and writings, and his Beyond A Boundary, ensure James’ legacy – if we can ignore the peccadilloes, and separate the chauvinist from the campaigner.