Tomorrow is the centenary of the birth of Dimitrios Tsafendas whose name probably means little to most people. But from first hearing and reading about him two decades ago I felt his story to be incredibly sad.

When Dimitri was a young boy in Mozambique (he was born in Lourenço Marques, now Maputo), it was discovered that he was infested with a giant tapeworm. A Portuguese chemist gave Dimitri’s Greek stepmother a powerful poison to help expel the worm and told her to keep its head for him to study. Dimitri passed the worm, which was two or three feet long, but panicked because his stepmother flushed it into the sewers – still alive, he believed.

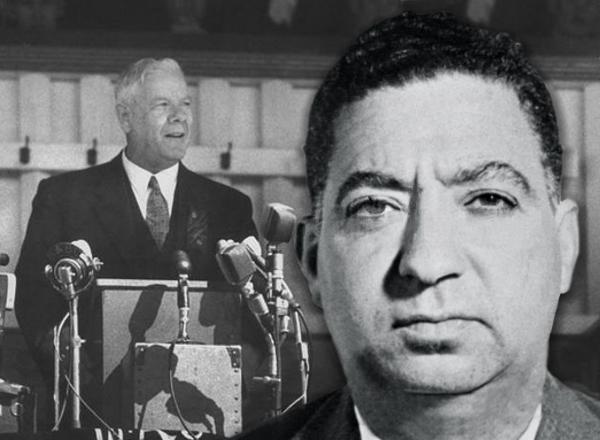

Years later, in Cape Town, Dimitri went into a store and bought a large knife. A few hours later he went to the all-white House of Assembly where he worked as a uniformed parliamentary messenger. He was 48-years-of age, had an IQ of 125 and could speak eight languages, but as a designated ‘coloured’ person he worked as a uniformed parliamentary messenger in the all-white House of Assembly.

That afternoon Prime Minister Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid and who was responsible for the Sharpeville massacre, was exchanging greetings with those around him as he made his way towards the green leather benches. Dimitri briskly walked across the floor to where Verwoerd had sat down, drew his knife and stabbed Verwoerd four times in the chest. Other members of parliament rushed forward and overpowered the court messenger. Mrs Verwoerd ran down from the wives’ gallery and kissed her husband as doctors tried to save his life but he was dead on arrival at hospital.

It was September 6th, 1966.

Verwoerd had survived an earlier assassination attempt and believed that God had intervened to save his life. The God of Apartheid, no doubt.

Ironically, the Ministry of the Interior had just discovered that Tsafendas was actually banned from South Africa. It had written him a letter informing him that he was to be deported. The letter was still in an out-tray waiting to be posted.

Within days of Dimitri’s arrest stories appeared in the media claiming that he told police that a giant tapeworm ordered him to assassinate Verwoerd. One psychiatrist quoted him as saying, “I don’t think I will be able to live in Cape Town after this, because of public opinion, you know… If I was ever offered a job in the House of Assembly again I do not think I would be able to face up to it.”

South African blacks, who one would have thought should have been dancing in the streets celebrating the assassination, did not know how to respond to this killing by a loner, who had no party political ties and who was described as just a crazy Greek.

I came across the name Tsafendas many years ago and actually joked about him in a Magill magazine interview I conducted with F.W. de Klerk. I said that it was a sign of the time that when I met the former South African prime minister his security was zilch and that the only Greek around was Elita, his new wife.

Of course, I was wrong in being so glib. It is only when you probe further that you discover a life at the end of a name, in Tsafendas’ case a sad life, a man who suffered racial abuse, and mental torment.

In a successful blend of fiction and biography Henrik Van Woerden tells the story of this unlikely assassin in his 2000 book, A Mouthful of Glass.

Tsafendas was born in Mozambique, the son of a marine engineer of Greek extraction and a mother, a 17-year-old maid of mixed European and African descent, whom his father disowned and he never knew. He was sent to live with his grandmother in Egypt but she died when he was six and he returned to Mozambique where his father had remarried a young Greek woman. At school Dimitri was nicknamed, ‘Blackie’ because of his skin. It was only later that he found out that he was ‘coloured’ and illegitimate.

In 1936 he moved to South Africa, was a member of the Communist Party for a while, then joined the Merchant Navy and travelled the world. His mental instability was apparent and he ended up spending time in various psychiatric institutions, being imprisoned in several countries because his papers were not in order, and being deported.

In 1964 he returned to Africa, first to Mozambique to try to identify his mother and find her grave, before slipping into South Africa (where he was officially black-listed) and settling in the Cape where he was befriended by Patrick and Louise O’Ryan.

No country wanted him. No country recognised him.

After his arrest he told police, “I was so disgusted by the racial policy that I went through with my plan to kill the prime minister.” A judge found that he was unfit to stand trial and committed him. But instead of being sent to a mental hospital, the government exploited a loophole in the law and he was placed in death row for twenty-three years. There, warders spat in his food, urinated in his coffee and beat him while he was held in a strait-jacket. They destroyed the only photograph he had of himself as a child. His cell was next to the gallows where his fellow prisoners in batches of up to seven at a time were hanged. He heard their last screams and cries.

It was only in July 1994 that he was moved to a lower-security prison/hospital for infirm men. Among those who visited him were the late David Beresford (who wrote Ten Men Dead, about the 1981 hunger strike) and Henrik Van Woerden who visited him several times for his book, though for his re-creations of Dimitri’s past history he relies heavily on papers and reports that were never revealed because there was no trial. On one visit to the hospital there was such a racket that their exchanges had to be written on a pad. He says that Tsafendas wrote in untidy, block letters: ‘I REGRET WHAT HAPPENED.’

“He began to cry. I took both his shoulders in my hands and shouted as loudly as I could: ‘Never mind. Other times. Not your fault.’ ‘A whole other time,’ he sobbed. ‘I am not that kind of person. It was something that happened. It was not in my nature. Besides, I was sick… It will not die. I’m helpless against this Dragon-Tapeworm.’”

Dimitri also asked him who the president of South Africa was now. “I wrote the name ‘Mandela’ and showed it to him. ‘Nelson Mandela…? I would like to speak to him. He’s a very strong man.’”

Demitrios Tsafendas died aged 81, in October 1999, from pneumonia. About ten people, mostly members of the Greek community, spared him a pauper’s funeral and gave him a proper burial, though his grave remains unmarked in the prison grounds. No one from the ANC attended, even though he had struck a significant blow against apartheid. Mourners were outnumbered by the press, who were outnumbered by plain clothes and uniformed police officers.

One card on a wreath of white lilies on his grave read: “Displaced Person, Sailor, Christian, Communist, Liberation Fighter, Political Prisoner, Hero. Remembered By His Friends.”

And, hopefully, us.