Among all the protagonists to the recent conflict in the North there is one side, above all others, which urgently needs to ‘draw a line through the past’, as if that were ever possible. It’s not that it seriously believes that the stroke of a pen or a piece of legislation will lead to reconciliation or consolidate peace.

No, its motive is completely base and self-serving.

If investigations continue into collusion and the use of agents provocateurs, if legacy inquests into decades-old killings go ahead, the paper trail will inevitably lead to 10 Downing Street and prove that successive British governments, their forces and surrogates, played a major role in generating the conflict, with the central characters rarely if ever having been held to account. The danger for the political establishment is that if individuals in their forces are placed in jeopardy by laws intended only for suppressing the enemy they will whistle-blow and reveal the truth about the political chain of command in Britain’s dirty war.

Other protagonists may well be caught up in any investigative process and face exposure but it is the British who have most to fear from the truth, the emergence of a narrative which challenges their promoted orthodoxy around responsibility for the conflict.

Who knew that the dead could be so powerful. As the writer Tim O’Grady noted, ‘the past keeps calling for a reckoning.’

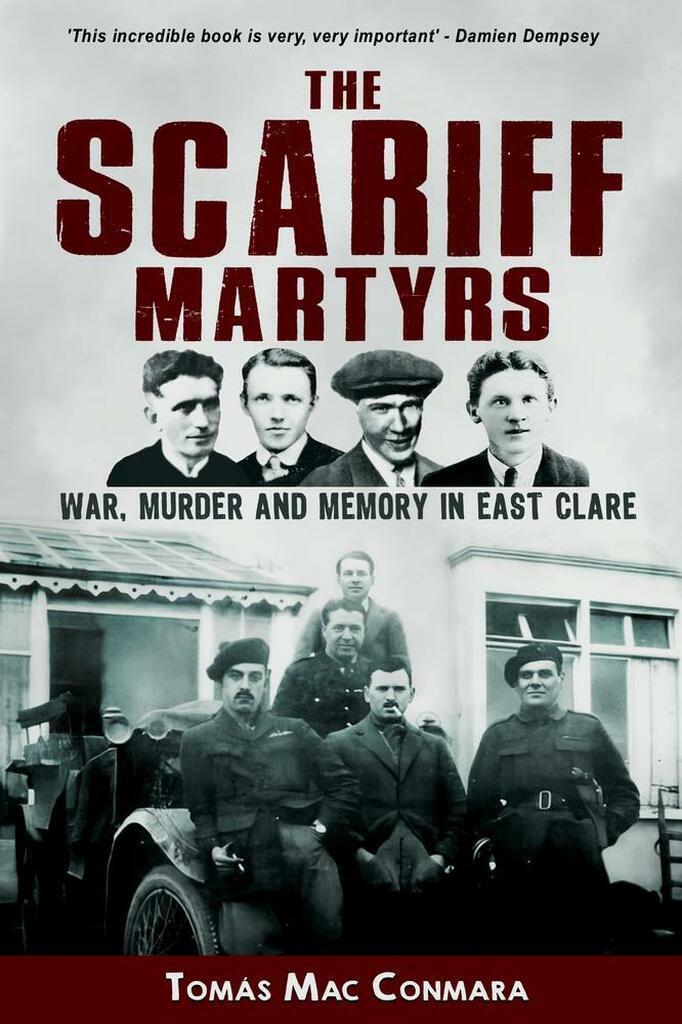

The power of the past to impact on the present and on memory, the power of the voices of the dead to be heard, the fact that they will not fade or go away, was illustrated most recently in the book, The Scariff Martyrs – War, Murder and Memory in East Clare by Tomás Mac Conmara. The author has written before on this theme in both The Time of the Tans: An Oral History of the War of Independence in County Clare, and Days of Hunger. About his methodology in those books I singled out his perseverance and noted that he had spent years ‘speaking to and recording the actual people who lived and made history, their contemporaries, and their children – the carriers of folk memory … Without writers like Mac Conmara history would be poorer, certainly distorted… By insisting on giving voice to the local, he offers us a deeper understanding of what really happened, the energy and power behind momentous change.’

In November 2008, Mac Conmara interviewed 105-year-old Margaret Hoey in her nursing home.

‘Do you remember the time the four lads were killed on the Bridge of Killaloe?’ he asked. He says her demeanour changed to one of visible sadness as she recalled the night when as a sixteen-year-old there was a loud bang on her door. A young IRA Volunteer brought news to her mother about the capture, interrogation and murder of four young men by the Auxiliaries, three of whom Margaret knew. Margaret and her mother quickly made their way to other safe houses where men on the run were staying to alert them that their security might be compromised.

On 16 November 1920 the Auxiliaries acting on a tip-off had crept up and raided Williamstown House and surprised three IRA men hiding there. Along with the caretaker, Michael Egan, they brought the three, Alphie Rodgers, Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon and Martin Gildea to their base at the commandeered Lakeside Hotel. The men were volunteers in the Scariff Company, 4th Battalion, East Clare IRA: Egan a sympathiser. In the barracks they were tortured for several hours, beaten beyond recognition according to some accounts, before being taken to Killaloe Bridge where they were executed. Each man was shot about seventeen times, bullets fired at close range to the extent that some rounds singed their hair. In a statement the British authorities issued the usual pretext that the prisoners had been shot whilst trying to escape and refused to release their bodies for four days whilst they held an inquiry.

The inquiry panel was composed exclusively of British military personnel. The president of the court, a major in the Grenadier Guards, would later become a Conservative MP. The verdict of shot whilst trying to escape was endorsed by the British government. There was no justice then, just as there is no justice now for many of the victims of our conflict. Mac Conmara’s research shows that complicit in the killings were the RIC, some of whom were subsequently awarded the constabulary medal.

Another callous act was to occur in Scariff. Before the families were able to collect the bodies Auxiliaries forced their way into McMahon’s pub. There they compelled the family of Brud McMahon, whom they had just killed, to serve them drink. Brud’s mother Bridget was made to endure them taunting her with a rendition of the song, ‘Where is my wandering boy tonight?’

Although their deaths were overshadowed by other, higher profiled events – MacSwiney had died on hunger strike three weeks earlier, and Kevin Barry had been hanged on 1 November – the killings were seared into the memory of the local community. Mac Conmara fleshes out the personalities of the victims, whose deaths were later memorialised in song (Christy Moore sang about the killings on a 1970s album), at a stone on the bridge marking the spot where they died, and with annual commemorations at their graves in Scariff.

Writing in the late 1930s schoolgirl Brigid McMahon (niece of ‘Brud’ McMahon) said, ‘In hundreds of years when we are dead and gone some child who will be passing will ask the story of that stone.’

On the second anniversary of their deaths (during the Civil War) the guard of honour at the commemoration was made up of East Clare members of the Free State Army – on the assumption that the martyred dead would have supported the July 1921 Truce and subsequent Treaty. The state would later withdraw completely from the commemorations but when Sinn Féin continued to honour them at their graveside they were frustrated by the parish priest who labelled them ‘subversives’.

On the second anniversary of their deaths (during the Civil War) the guard of honour at the commemoration was made up of East Clare members of the Free State Army – on the assumption that the martyred dead would have supported the July 1921 Truce and subsequent Treaty. The state would later withdraw completely from the commemorations but when Sinn Féin continued to honour them at their graveside they were frustrated by the parish priest who labelled them ‘subversives’.

Mac Conmara gives us a fairly detailed account of nationalism, Fenianism and republicanism in East Clare before the Tan War; the depredations and destruction by Crown Forces, and IRA activity.

At the time of the killings there was much speculation and rumour about who had been the informer, suspicion falling on at least seven individuals, including one local loyalist and an RIC pensioner.

‘The influence that the informer has had on social memory surrounding the incident is colossal,’ says the author, and ‘reflected in the concluding lines of the song which declares emphatically, “the day will come when all will know who sold their lives away.”’

Interestingly, over the passage of time, an original verse, much rawer and visceral, appears to have been dropped in later versions:

May every curse fall on the wretch who sold their lives away,

And may the fate of Judas, eer long be his, someday.

And may the flesh fall off his bones and may his sight decline,

May his cursed soul be tortured until the end of time.

Reminders of treachery are demoralising, particularly in liberation struggles where the consequences are devastating and communally divisive for decades thereafter.

Another story told in the book will serve as an epilogue to this review because it demonstrates the consistency of the contempt in which British soldiers hold Irish lives and concerns the case of Jim ‘Birdie’ Grogan. Birdie lived a few miles from Scariff, and was described as being ‘simple’ and by his father with having ‘a weak brain’ and ‘no intellect’ – and clearly harmless. In June 1921 Birdie was on his way to chapel at Clonusker on a remote road when the sound of an approaching British army lorry frightened him. He ran towards his home. A soldier, Private Biggs, jumped from the vehicle, took aim and, without warning, shot him dead. The soldier claimed he had ignored an order to stop. They say that history has a way of repeating itself. 1974 – a remote country field near Benburb in County Tyrone. John Pat Cunningham, who had the mental age of a child, and who had a deep fear of soldiers, was crossing a field when he saw a patrol. He ran away. A soldier from the Life Guards regiment, Dennis Hutchings, took aim and shot him in the back, killing him. The case of Hutchings – who actually was facing trial but died of Covid – and several other cases pending decisions by the Director of Public Prosecutions has led to a campaign by British army ‘veterans’ to halt court cases, and is another reason why the British government is planning to announce legislation next month banning prosecutions.

This is a brilliant work and testimony to the fact that inconvenient though history might be to some, the dead remain alive in the memory of this once oppressed community. If the only justice they receive one hundred years later is one of reminding Ireland of why they fought and why they suffered and died then their legacy is empowering and inspiring and immortal.

The Scariff Martyrs – War, Murder and Memory in East Clare by Tomás Mac Conmara is published by Mercier Press and can be ordered here.