“The twentieth century produced the greatest hopes for mankind,” writes Slavko Goldstein, in this informative but depressing memoir, 1941 – The Year That Keeps Returning. “It became the graveyard of great ideals. It taught us that ideals are most often a seductive chimera and that doubt is not a fatal weakness but a necessary defense against fatal beliefs.”

“The twentieth century produced the greatest hopes for mankind,” writes Slavko Goldstein, in this informative but depressing memoir, 1941 – The Year That Keeps Returning. “It became the graveyard of great ideals. It taught us that ideals are most often a seductive chimera and that doubt is not a fatal weakness but a necessary defense against fatal beliefs.”

Goldstein gives a detailed account of life in Croatia during WWII and the fate of the Jews and Serbian Orthodox Christians at the hands of the Ustasha fascists who seized power and established, with Hitler and Mussolini’s blessing, the Independent State of Croatia. Goldstein’s father and many of his family members were murdered during the war and young Goldstein and his mother fought with the Partisans led by Tito. (The Partisans and the National Liberation Army were the only army in which Croats and Serbs were on the same side of the battle front.)

Tito’s ‘unification’ of Yugoslavia (‘Brotherhood and Unity) did temper local hatreds but also led to the suppression of freedom. Disillusioned, Goldstein immigrated to Israel before returning to Croatia. He had no time for the “fetishism of the state and a fetishism of the nation” and recalls Einstein’s famous claim that it is more difficult to break human prejudices than to break the atom.

“We were mature enough to resist evil, but we were not mature enough to crown our victory humanely. Like many military victories in history, ours did not remain untainted either.”

This comment, in particular, refers to the slaughter (“an orgy of vengeful wrath”) by the Partisans of Ustasha forces, their families, sympathisers, and those ‘mistaken’ as collaborators, 70,000 in total, who attempted to flee into Austria and surrender to the Allies but were refused access. The aftermath of the ‘Bleiburg repatriations’ and ‘the Way of the Cross’, as their surrender and return and massacre came to be called, remains a taboo topic and a huge challenge to Croatia/Serbian society on how to deal with the past.

‘Way of the Cross’, says Goldstein, “is an apt metaphor for the tortuous, several-hundred-mile-long march of starving and thirsty prisoners, many of whom could not withstand the torment and were killed.”

The past haunts the present not just in Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, but, as we know only too well, in Ireland.

“Although some years later the Germans, with some self-satisfaction, created the word Vergangenheitsbewältigung (overcoming the past), I fear that they still haven’t fully confronted this past, even less so in the case of our eastern neighbours and here in Croatia. Hidden diseases still fester, the most stubborn roots of which lie in 1941, even if the years that came before and after aren’t guiltless either,” says the author.

And, of course, 1941 did return again in 1991 with the break-up of Yugoslavia, with the fall of communism, and a bloody civil war over contested territories, particularly in eastern Croatia.

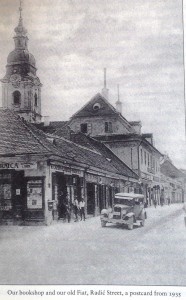

Goldstein’s father, a bookseller, was arrested with other intellectuals and held in Zagreb Jail before being taken away and killed in some dark, unknown place. From prison he wrote to his son: “It is better to bear an injustice than to commit one.” They knew that he had been taken from the prison because a railway worker, again at great risk to himself, found a piece of rolled-up paper lying beside the track and bravely brought it to Goldstein. It had been thrown from the train and said, “I would be grateful if any honest passer-by would deliver this note to my wife.” It had her address written on it and a message that they were being transported to Lika (and to their deaths).

Goldstein’s father, a bookseller, was arrested with other intellectuals and held in Zagreb Jail before being taken away and killed in some dark, unknown place. From prison he wrote to his son: “It is better to bear an injustice than to commit one.” They knew that he had been taken from the prison because a railway worker, again at great risk to himself, found a piece of rolled-up paper lying beside the track and bravely brought it to Goldstein. It had been thrown from the train and said, “I would be grateful if any honest passer-by would deliver this note to my wife.” It had her address written on it and a message that they were being transported to Lika (and to their deaths).

“I have not written the word ‘bravely’ by accident,” says Goldstein. “At that time, compassion and honesty were not enough for a person to take a prisoner’s randomly thrown letter so promptly to an unknown addressee, the prisoner’s wife. Indeed, the man must have possessed courage.”

This war was intimate, Croat Catholic neighbour against Orthodox Christian Serb, with thousands of incidents of cruelty and fewer acts of kindness and help involving great risk. One wonders if society can overcome such a bloody past. Goldstein was grateful to the Starešinić family who had taken over their dispossessed shop but who defied the anti-Jewish Ustasha laws and kept their property safe.

In one Ustasha massacre the militia raided a small village and took away 83 people, only six of whom were men. The rest were women and children (ten of whom were younger than five years old). They were tied together in groups of eight, shot and thrown into a deep cavern. One victim, a young woman, wounded, and lying among the dead, managed to drag herself out of the cavern and, “completely distraught, ran into Luk Miškulin, a resident of Boričevac and the father of two of the Ustasha who had participated in the killing. He revived her with some water and food and guided her on the road to her people, evading the Ustasha guards and patrols along the way.”

Croatia was also occupied in part by Italian soldiers who when quartered with Jewish families were kind and sympathetic. Yet Goldstein witnessed Italian soldiers robbing and setting fire to houses in two little villages – to the last house, the last barn, the last hayloft.

He wondered: “Were the men committing this evil – looting, robbing, burning, leaving only desolation in their wake, and taking 1,100 innocent villagers away to internment – the same good-natured, cheerful soldiers who softly sang “Mama son’ tanto felice” on the Karlovac promenade and played the melody of the “Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves” from Nabucco in front of Lopašić’s monument, and the same polite officers who brought sweets to the children of their landlords and saved those in danger?”

Yet, other Italian commanders adopted and cared for Serbian children who had been orphaned by the Ustasha massacres and some sheltered Jews in the northern Croatian coastal regions and Dalmatia despite demands from the Ustasha authorities and Nazi representatives to hand them over.

In the Ustasha death camp of Jasenovac a prisoner asked the camp commander whether he feared God’s punishment for the godless acts he was committing, to which the commander responded: “Say nothing to me. I know I will burn in hell for what I have done and for what I will do. But I will burn for Croatia.”

It is difficult to imagine a more descriptive characterisation of the fanaticism of hatred, says Goldstein.

It took me a long time to finish this book and not because it is 600 pages long but because I found it depressing yet compelling. I had to repeatedly put it down, only to pick it up again.

There were two villages, one Croat, one Serb, where at the beginning of the twentieth century neighbour would help neighbour restore a house, build a road. Then came 1941. Over the years, relations were being somewhat restored. Then came 1991.

Today old acquaintances pass by each other without a greeting. “Other people would greet each other coldly, but it was rare that anyone would stop and ask an old friend, ‘How are you? How are the wife and children?’”